The next three years will be crucially important for refining a model of independence relevant for Wales in today’s world. In the wake of Brexit, Wales needs to protect its essential connection with the continent of Europe – the source of our values and civilisation, and the context of practical independence for our country.

Nearly a century ago, the Plaid Cymru leader Saunders Lewis set out a vision of Wales in Europe. The Plaid Cymru History Society is proud to publish in full the important lecture delivered by Dafydd Wigley during the 2023 Eisteddfod Llŷn ac Eifionydd National Eisteddfod – which shows that this vision is today more relevant than ever.

Saunders Lewis, Wales and Europe

[In Memory of Emrys Bennett Owen,

who opened my eyes to his vision]

I am grateful to the Eisteddfod for being for this forum to re-examine ideas that are highly relevant to this period of time; and to thank Swansea University for inviting to deliver a lecture on the subject of “Saunders Lewis, Wales and Europe”. And today, it is appropriate to remember that it was in Pwllheli during the 1925 Eisteddfod that Saunders Lewis and five others came together to set up Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru, the Welsh National Party.

May I acknowledge my gratitude to the Uwch-Gwyrfai History Society for the opportunity of delivering the first version of this lecture, and pay tribute to the outstanding work of Geraint Jones, Marian Elias, Gina Gwyrfai and Dawi Griffith. And congratulations to Geraint on his gaining the T.H. Parry Williams award; an award he fully merits. Another lecture was presented to the Society last year by Ieuan Wyn, with the title of “Darlith Saunders a’i dylanwad” (Saunders’ lecture and its influence), which is available as a pamphlet – dealing principally with the impact of the radio lecture by Saunders Lewis, Tynged yr Iaith (the destiny of the language).

This morning, I wish to deal with another of Saunders Lewis’s lectures, the electrifying one he gave in Machynlleth in 1926, under the title Egwyddorion Cenedlaetholdeb, or The Principles of Nationalism. To some of you, what I have to say will be neither new nor original; after all, I am a politician, not an author or a historian. But I feel passionately that Saunders Lewis’s vision, interpreting Wales in the context of Europe, is fundamental to the current project of securing an independent Wales; and I want to help the younger generation to appreciate Saunders Lewis’s leadership a century ago.

The next three years, which span the centenary of the lecture, will be crucially important for refining a model of independence that is relevant for this age. Especially so, as we consider – as we have to following Brexit – how Wales can protect its essential connection with the continent of Europe, the source of our values and civilisation, and the indispensable context for practical independence.

We also remember that Saunders was a University lecturer in Swansea between 1921 and 1936, before he paid the price for acting according to his conscience in September 1936 when the Bombing School was burnt, just three miles away from this place. It is good that the University has acknowledged its connection with this hero, in the words of Williams Parry, “the most learned in our midst”. And I thank Professor Daniel Williams for the Seminar he organised in 2011, which marks the 75th anniversary of the dismissal.

It is good also to recall that, earlier this year, an enormous rally calling for independence took place in Swansea, with six thousand in the procession – this at a time when the concept of independence has aroused the interest of over a third of the people of Wales. So it is right for us to consider once again the vision of Saunders Lewis. We don’t have to agree with every word he pronounced; and we have to remember that the Wales of 1926 was a very different place to the country we have today. At that time we did not exist politically: according to the index of Encyclopaedia Britannica, with its arrogant statement – “For Wales: see England”.

There was no Welsh Parliament, no Secretary of State, and no status for the Welsh language. That was the backdrop for Sounder’s revolutionary ideas, in the wake of the most bloody war ever seen by the world; a war where he as a soldier was wounded in the trenches in France; a war which, in name, was fought to protect small nations – but Wales, sadly, was not among them. But now, after four centuries of servility, here was this diminutive, frail man was daring to challenge it all, making Wales an essential part of the European continent, not the back yard of an arrogant and self-satisfied empire.

The Wales we have today would not exist but for the vision of Saunders Lewis: he cannot be ignored. This is evident in recent books, such as the work of Professor Richard Wyn Jones, who demolishes the completely groundless accusations of fascist tendencies by Saunders and Plaid Cymru. It is confirmed by Professor M Wynn Thomas, Swansea, in his volume Eutopia, which assesses the vision of Saunders Lewis. He is critical, in an objective way, but acknowledges that his vision remains “an interesting, brave and intellectually penetrating endeavour to frame a uniquely Welsh analysis of European affairs”. It is therefore appropriate to have a forum to examine the abiding significance of his European vision in this Eisteddfod.

*****

Throughout the centuries, and during the times of Owain Lawgoch, Owain Glyndŵr, Gruffydd Robert, Richard Price, Emrys ap Iwan and Henry Richard, our link with Europe has been a key element of our identity as a nation. And today, when considering the significance of the European dimension for Wales it is impossible to do that without taking into account the standpoint presented to Plaid Cymru in its early days by its President.

During the period that followed the second world war, there was a tendency to scorn and belittle its political vision and beliefs; partly by Plaid Cymru’s political adversaries; and partly on account of the claim that its values and vision were relevant to another era – an era whose values were very different to those of our time. I shall try and answer that sort of accusation.

Saunders Lewis was just a name to me until I turned on the radio in February 1962. The programme had already begun, and so I was no wiser as to who was speaking. I was entranced by the unfamiliar, thin voice that was saying such great things, things you would never hear on the BBC! Who was talking, and what was the context? Yes, it was the lecture “Tynged yr Iaith” (The Destiny of the Language) – and quite by chance I was listening amazed in my bedroom in Manchester University.

I met Saunders Lewis only three times – the first occasion being at the time of the 1975 referendum 1975 on Britain’s membership of the European Common Market. I went to his home in Penarth in search of consolation at a time when Plaid Cymru – quite incredibly, to me – was campaigning against membership. Like me, he could not believe that the party was so short-sighted. A decade later, I had the unexpected privilege of bearing his coffin, along with Meredydd Evans, Geraint Gruffydd and Dafydd Iwan. I believe I was accorded this privilege because the European dimension is central to my politics, as it was for him; and that I was entranced by his vision of the rightful role of Wales – and the Welsh heritage – within the Europe’s cultural mainstream.

****

Saunders Lewis was born in 1893 in Wallasey, near Liverpool, the son of a Methodist Minister. I do not know at what age he became interested in our continent’s culture, but by 1912 he was studying French in Liverpool University; and this proved advantageous for him after he enlisted, as did so many of his fellow-students, in the army in 1914.

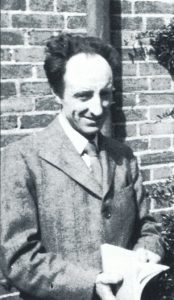

Saunders Lewis, at the time of the First World War,

Saunders Lewis, at the time of the First World War,

as a subaltern in the South Wales Borderers

By 1916 he was describing his life fighting in the trenches, but billeted in a French village fifteen miles behind the battlefield. In letters to his girl friend, Margaret Gilcriest, he described the experience of socialising with the local French people; and describing it as much more acceptable than the macho-masculine company of his fellow-soldiers. He wrote of the open and spontaneous nature of French people, and that this was in sharp contrast to the company of those in the trenches.

He says that returning to the front line was like going to another country – having to go back to the middle of Englishness; to English foul language and all the attitudes of “John Bull’s own ways of eating, drinking, and geing generally half a gentleman by effort, and half a Bull by nature and instinct.” The company of French people, cheerful, open and without malice was quite different to life in the trenches where he had to live what he describes as “the boorish life of an English Squire”. There can be no doubt that these experiences confirmed his feeling that the Welsh had more in common with their cousins on the continent than with the values and attitudes of most of the people of England.

******

Saunders Lewis,

Saunders Lewis,

President of Plaid Cymru between 1926 and 1939

Saunders Lewis, from his early days as the leader of the National Party placed his political beliefs in the context of Europe. He made this quite explicit in his great lecture to the first Plaid Cymru Summer School in Machynlleth in 1926.

In the lecture, “Egwyddorion Cenedlaetholdeb” (The Principles of Nationalism) – and I wish to quote a substantial passage to present it to a new generation – Saunders Lewis says as follows – :

5] “In medieval Europe, no one country …… claimed that its government within its own boundaries was the supreme and only authority. Every nation and every king recognised that there was an authority higher than state authority, that there was a law higher than the king’s law, and that there was a court to which appeal could be made from the State courts.

“That authority was the moral authority, the authority of Christianity. The Christian Church was sovereign in Europe, and Church law was the only final law.

“For a while Europe was one, with every part of it recognising its dependence, every country recognising that it was not free, nor had any right to govern itself as it pleased regardless of other countries. And Europe’s oneness in that age, its oneness in moral principle and under one law, protected the culture of every land and region.

“For one of the profoundest ideas of the Middle Ages, an idea Christianity inherited from the Greeks, was the idea that unity contains variety. There was one law and one civilisation throughout Europe, but that law, that civilisation took on many forms and many colours…..

“Because there was one law and one authority throughout Europe, Welsh civilisation was safe, and the Welsh language and the special Welsh way of life and society. The idea of independence did not exist in Europe nor the idea of nationalism, and so no-one thought that the civilisation of one part was a threat to that of another, nor that a multiplicity of languages was inimical to unity.”

He goes on to ask:

“What, then, is our nationalism? This, …… a denial of the benefits of political uniformity, and a demonstration of its ill effects, thereby arguing in favour of the principle of unity and variety. Not a fight for Wales’ independence but for Wales’ civilisation.” [I shall come back to that shortly!] “A claim that she should have a seat in the Society of Nations and European society by virtue of the value of her civilisation. ……. Europe will return when the countries recognise they are all subjects and dependent. …… So let us insist on having, not independence but freedom. And freedom in this affair means responsibility. We who are Welsh claim that we are responsible for civilisation and social ways of life in our part of Europe. That is the political ambition of the National Party.”

I do not want to split hairs about the word “independence”. It can have a variety of meanings for different people. The meaning of independence for UKIP was leaving the European Union; its meaning for the SNP is being able to join the European Union. Saunders himself said in his address to the Llanwrtyd Summer School in 1930: “We will go to Parliament …to reveal to Wales how we have to act in order to win independence.” [Y Ddraig Goch, September 1930]. If the greatest among us mix their diction, who are we to split hairs! It is the big concept that is important; and about that, there is no doubt and no confusion about where Saunders Lewis stands – securing for Wales “her place in the community of Europe by virtue of her civilisation.”

I have no time this morning to pursue the attractive red herring of asking “What is the value of the civilisation we possess in Wales today?” There are many people better qualified than myself to analyse that. Have a go! But I do believe that it is essential that we should advocate independence for a purpose; and that purpose should be to safeguard, develop, enrich, share and pass on what we regard as Welsh civilisation. And we should never forget that the natural home for our civilisation lies within the framework of Europe.

- Myrddin Lloyd, in his essay on the political ideas of Saunders Lewis, also refers to the theme of Europe, when he writes as follows:

“A nation’s foundations are therefore moral and spiritual; and its destiny does not rest on any form of complete independence; nor does its dignity require that. It can present itself to many sorts of relationships. And it can cope readily with many frustrations. One of its virtues is its freedom, and in the same way that people link themselves naturally together in families, and in various other societies, as they find themselves in association with their fellow-people, so nations by virtue of moral law acknowledge many relationships with each other.”

Myrddin Lloyd continues:

“In his attack on Fascism in 1934 (an important article that some choose to ignore) Saunders Lewis said that Fascism maintains that every individual belongs to the state , and that the claims of the State are unconditional. ‘The Welsh National Party maintains that the nation is a society of societies, and that the rights of smaller societies, such as the family, the locality, the trade union, the workplace, the chapel or church, are all worthy of respect.

“The State has no right to ride roughshod over the rights of these societies and there are also rights beyond the boundaries of the nation that every man and every country should respect.”

It is certain that the vision of Saunders Lewis is founded in part on the legacy that springs from Wales’s European roots. We should not think that commercial advantages of European unity are key to this vision; to the contrary. Material advantages are a secondary consideration; because Saunders set his vision on a spiritual rather than material foundations; and it is the European origin of this spiritual dimension that is important for him. This is seen in the Wednesday essays, when Saunders says as follows:

“The history of European civilisation – this is the history of a spiritual ideal …Tracing that ideal gives meaning to studying the history of Europe; it is that which gives Europe a unity.

There can be any number of influences on a country and its way of life. But what enters its life as a destiny, and decides its role in Europe’s heritage, is the particular moral ideal, the ideal first shaped by Greece. Greece is the starting point for our civilisation and the imprint of Greece remains upon it to this day.”

It is interesting to note the words of Patricia Elton Mayo, in her book “Roots of Identity: Adnabod y gwreiddiau”, where she wrote that as a author and dramatist recognised on the continent but unknown in England, Saunders Lewis emphasised the European context of Welsh civilisation, an obvious feature “before the English occupation isolated Wales from the mainstream of European cultural development”. This sort of perspective – springing from outside Wales, and recognising national developments in Wales as part of a European movement, reflects the viewpoint of Saunders Lewis, and sets it within a much broader context.

Saunders edited Y Ddraig Goch for years during the early phase of Plaid Cymru’s history. I shall be taking advantage of every opportunity to bring the European dimension to his analysis. For example, in the August 1929 editorial article that he wrote, under the title “Yma a thraw yn Ewrop: y lleiafrifoedd yn deffro” (“Here and there in Europe: the minorities awake”), he noted the national revival in Flanders, Catalunya, Malta, and Brittany and asks:

“What does all this prove? It proves that the minorities of Europe, the small countries that were swallowed up by larger ones during periods of oppression and centralisation of government, are now awakening in every part of our continent and are bringing a new spirit and ideal to European politics.”

Then he declares:

“The speciality and strength of Europe, in comparison with America, is the rich variety of her civilisation. ….If this is correct, our argument that the movement for self-government in Wales and in all the other countries benefits Europe and the world is also correct …..

“This European philosophy also drives leaders on the continent, …. who are seeking to lead Europe back from imperial materialism, from the short-sighted competition of the large centralised powers, to a new politics, a politics founded on a deeper understanding of the true nature and value of western civilisation.”

Saunders Lewis also sees self-government for Wales as part of establishing a better international order; an order that would aim at solving disputes by peaceful methods, not by fighting the bloody war that he witnessed in the trenches in France. His emphasis on developing international systems – and his repeated warnings that England would not wish to be part of such an order, provides the background for the politics of Gwynfor Evans, and for the stand taken by Adam Price against the Iraq War.

It is worth looking at this in detail, as the message is so relevant for our time, when England, once more, is turning its back on our continent and on the European Court of Justice. In his article “Lloegr ac Ewrop a Chymru” (Wales and Europe and England) in 1927 Saunders Lewis says:

“What is the foreign policy of England? Its guiding principle was set out finally and beyond doubt by Sir Austen Chamberlain (Britain’s Foreign Minister) in a meeting of the League of Nations in September. He said: ‘England belongs to a union of nations that is older than the League of Nations, which is the British Empire, and that if a collision occurs between the League of Nations and the Empire, then we have to back the Empire against the League of Nations.’”

It is relevant to remind ourselves that the Welsh Women’s “peace petition” collected in 1923, involved this very point – appealing to America to support the League of Nations as an essential foundation for building peace.

Saunders continues: “When Chamberlain said that, he spoke for England, not for his party …. Now, by virtue of this principle, England – unfortunately, we have to say Great Britain – although naturally and geographically and in part historically part of Europe and essential to Europe – nevertheless denies its association and its responsibility and leaves Europe today, as in 1914 and before, uncertain about its policy.”

Isn’t it incredible that we can say this, once more today? By failing to learn the lessons of history, we repeat the same mistakes. Last time this lead to fascism and to the 1939 war. God forbid we should experience that blood-stained lesson yet again.

Saunders goes on with this key statement, which did much to shape my own political convictions:-

“Bringing about political and economic unity within Europe is one of the foremost needs of our century. This is clearly seen by Europe’s small nations, and in order to ensure it they drew up the Protocol that binds countries to settle disputes by discussion and by law, and calls on all the other countries to unite and punish any country that breaks their commitment.”

To that end also, the small nations demanded that every country be bound to endorse a Permanent Court of International Justice, the aim of which was to get countries to accept the judgement of the Court on disputes between them and so avoid was.

“England refuses … because, as part of the Empire almost entirely outside Europe, she does not wish to attach herself to Europe …. She refuses … because the Government cannot ensure, if the court’s judgement were unfavourable to Britain, that it could be passed into law by a British Parliament; and secondly because the Government is sufficiently broad and strong to be able to defend its rights without depending on a court of law ……….”

Hasn’t this been clearly seen during the last seven years, by the attitude of supporters of Brexit towards the European Court of Justice?

Saunders’ essay continues:

“It can also be seen that England’s economic tendencies quite as much as her political tendencies, lead to war. The hope of political peace in Europe is to get Britain as an essential part of the European union of nations ….. But in Britain is there a European tradition? Is there here a nation that was an original part of the civilisation of the West, that thinks in the ways of the West, and can understand Europe, and be able to sympathise with her? The answer is: Wales.

“The Welsh are the only nation in Britain that formed part of the Roman Empire … The Welsh can understand Europe because they are part of the family.”

Friends, It is from these roots that the national movement in Wales has grown; and woe betide us if we forget it. Wales’ national civilisation includes our cultural heritage – our language, our literature, our music, our fine arts. It also includes our values, such as the emphasis we place on our social legacy, on equality; on the value of society in its own right, and not just the value of the individual and the family alone; and on the element of cooperation, as families, as communities and as countries, to protect our interests.

This is the essence of the fundamental difference between the politics of Wales and the politics of England; and because the Welsh Labour Party insists on tying itself to the English Labour Party, it fails to develop a philosophy and a political programme based on our

Such was the meaning of independence when Plaid Cymru was set up; and that is why Gwynfor Evans wrote in the sixties, “It was stated (by Blaid Cymru) from its outset that its aim is freedom, not independence”. This was the case because of Plaid’s commitment to empower Wales to play its part in international institutions, such as the League of Nations; national values as the foundation for its policies within Senedd Cymru.

At this point, I come back to the matter of ‘independence’. In the 1920s the policies of the London parties rejected sharing power with international bodies in order to protect Britain’s ‘independence’, and after the war the United Nations; and later on, the European Union.

It was only at the turn of the century, when the terms of membership of the European Union were redefined so that membership of the Union was open to ‘independent states, that Plaid Cymru changed its policy to one of independence. I myself voted for that, accepting that the first thing that happens to a country becoming part of the European Union is that it sacrifices part of its independence. Saunders Lewis, I am sure, would rejoice that Wales was embracing this as an aim.

Saunders Lewis, of course, was no Marxist. He acknowledged the importance of small businesses and cooperative businesses. He was most critical of Soviet Communism – and as a result he attracted the antagonism of those, both Welsh and English, who based their politics on Marxist analysis. But that does not make him a capitalist; placing him on the political spectrum is not a binary choice. Saunders made quite clear his opposition to international capitalism in the first chapter of Canlyn Arthur: “It should be said at once and clearly, that capitalism is one of the principal enemies of nationalism.” In an essay in 1932 he says: “For the Welsh nationalist, the Trade Unions are institutions that are priceless, valuable and advantageous for establishing in Wales the sort of society we aim at.”

So I completely reject the allegation that he was on the political right wing.

The aim of the European Community, from its early days, was to promote free trade on condition it was within a social framework, and so create equal terms for workers in the various countries rather than leaving them at the mercy of the market. Not many in Britain had recognised this in 1975, at the time of the referendum on Britain’s membership of the ‘Common Market’. So the English commercial right wing were longing to join the new system where they could, in their opinion, rake in more private profit. By contrast, the English left responded by opposing Common Market membership.

But both right and left misunderstood the European vision – the ambition of creating a social European just as much as an economic Europe: The idea of ‘Social Europe’ became an essential part of the fight for a social chapter within the European Union. When Maggie Thatcher and her crew realised the civilised implications of this part of the vision, they quickly went into reverse! This is why by the time of Brexit, much of the right wing in England was fiercely opposed to the European Union; while progressive elements on the left were in favour.

I do not agree with every word that fell from the lips of Saunders Lewis. Some points, credible at that period of time, appear outmoded today. But the mainstream of his vision is wholly relevant.

Another article with a European theme in the volume Canlyn Arthur is that on Tomáš Masaryk and the national revival of Bohemia; and this is a reply to those critics who complained that Plaid Cymru at that time was only interested in the small Celtic countries. Masaryk succeeded in laying the foundation for the Czech Republic which today is an independent country. Masaryk, like Saunders Lewis, stressed the role of culture as one of the essential elements of the national community; and like Saunders Lewis he saw his country in a European framework and within European ideals.

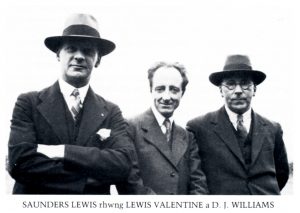

Saunders Lewis, with his fellow-defendants

Saunders Lewis, with his fellow-defendants

Lewis Valentine and D.J. Williams

at the time of the Penyberth trials

In his important contribution to the book “Presenting Saunders Lewis”, Dafydd Glyn Jones, writing about “Aspects of his work: his politics”, notes:

“Canlyn Arthur assumes throughout that the nation is the normal form of society in Europe and the basis of modern civilisation….. To be, to exist, and to be recognised by other national communities as exosting, this, Sanders Lewis maintains, is the only way …… in which Wales can fully and creatively participate in wider community.

“That participation, moreover, is indispensable if self-government is to have any meaning …. A Welsh parliament is necessary not in order that Wales may retire into self-sufficiency, but so that she may recover her contact with Europe.”

According to Dafydd Glyn, one of the strongest influences on Saunders Lewis was the French Catholic scholar, Jacques Maritain. He was one of the French leaders who maintained that there was an alternative for French Catholics other than supporting the quasi-fascist movement Action Française.

Maritain’s ideals included individual freedom, the need for order within society and a new pluralism that avoided dictatorship and conservative laissez-faire. He was influential in the task of drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and he campaigned to draw attention to the horrors of the Holocaust. In 1936, he published the book “Integral Humanism” which is regarded as a work that inspired the Christian Democrat movement in Europe. He was a close friend of i Robert Schuman, the Foreign Minister of France, after the war – the person who could claim, before anyone else, to be founder of the European Union!

A valuable work on the importance of the ideas of Saunders Lewis about the essential relationship between Wales and Europe has been contributed by Dr Emyr Williams, who took a doctorate in Cardiff with his thesis on “The Social and Political thought of Saunders Lewis”.

Emyr Williams traces the influence of Maritain on Saunders; and cites Maritain’s conclusion that the concept of sovereignty is intrinsically wrong because “political authority arises from the people, the body politic, and does not descend from above. This is crucial in seeking to understand Saunders Lewis’ thought regarding the concept of sovereignty …”

I am indebted to Emyr Williams for his help and for being able to study his research work. Among his conclusions are the following:

- The concept of a centralised European superstate is unacceptable to Saunders Lewis;

- That his vision is based on the principles of federalism and subsidiary;

- That his model for Europe is one of multilevel, plural governance;

- That the element of national cultural continuity is an essential part of the European concept, and a central part of European identity.

According to Emyr Williams, “Saunders Lewis’ Catholicism and Francophilism (sic) was undoubtedly to inform his view of Welsh culture being part of a broader European Christian heritage; seeking to move Wales away from the parochial relationship with England and Britain, and seeking to engage it both culturally and politically with the wider world.”

Saunders Lewis acknowledges that he had been influenced by the work of Emrys ap Iwan – in particular by the book by T. Gwynn Jones on Emrys ap Iwan, described by Saunders as “One of those books that changes history and influences an entire generation, giving inspiration and direction to its thinking.”. Emrys ap Iwan, like Saunders Lewis drew much of his inspiration from France, and also from Germany where he had been a teacher. Emrys ap Iwan coined the term “ymreolaeth”, self-government; defining it in federal terms and using Switzerland as a model.

According to Saunders Lewis, the French philosopher and historian, Etienne Gilson, was one of the main influences on him; and Gilson himself was an authority on the work of Descartes, and cooperated closely with Jacques Maritain! Some say that it was his own awakening to the central importance of the European dimension brought Saunders Lewis to develop his political and national consciousness.

There was a time – in the sixties and seventies – when many within the national movement saw the European Union as an impediment to Welsh independence. In my opinion today – just as it was a century ago when Saunders Lewis was refining his vision of Wales – it is not Europe that threatens the future of Wales, or the values of Wales, but the imperialistic mentality of Westminster, which is as true today as it was in the days of Austen Chamberlain.

From our perspective today, what is important to remember is first of all, why did Saunders Lewis look to our European roots for inspiration? Cultural and religious reasons account for this, as our identity and culture spring from our European roots. Our values have developed from these roots, and for me this aspect is absolutely fundamental.

But there is also another most important reason why we should not give up on the task of uniting our continent; and we are reminded of this by the recent history of Ukraine. Some of us here today have relatives who suffered – or even lost their lives – in the two terrible wars fought between the nations of Europe during the first half of the twentieth century. Let us never forget that people came together after the second war with the aim of creating a new, peaceful unity for our continent.

In conclusion, I return to the thesis of Emyr Williams – who underlines the fact that Saunders Lewis did not set national sovereignty in an independent state as the foundation of his Welsh nationalism. And this, say some political scientists, makes him unique for his period, and far ahead of his time. He is certainly not isolated in the mediaeval past, as his political enemies would have us believe.

Emyr Williams worked on his thesis partly because there had been no effort since the 1970s to reassess Saunders Lewis and his political ideas in the light of the massive changes of the last forty years, which by now include:

- Britain’s entry into the European Union, followed by its regrettable departure;

- the development of the European social chapter, the fall of communism and European reunification;

- smaller countries achieving full membership of the European Union;

- establishment of a legislative parliament for Wales;

- laws that give official status to the Welsh language; and

- growth in support for independence in Scotland and in Wales.

These all confirm the need to reassess the values and political message of Saunders Lewis.

Emyr Williams says of Saunders Lewis:

“Instead of viewing a place for the Welsh nation within a hierarchical British Empire, he sees a European political and economic union as necessary to the political vitality of the “small nations of Europe” in an egalitarian mould. The idea of a European union is therefore integral to his political thought.”

The message comes in a sentence:

“The development of the European Union as well as of its inherent principle of subsidiarity and multi level governance therefore requires that Saunders Lewis’ thought be re-examined.”

And that is also my message today, from the platform of the Literary Pavilion, to look once more at the teaching of one of the greatest writers of Wales, one who shaped a vision for the Wales of today – whether in terms of language rights, relationship with our continent, social justice or what is vital for civilised nationhood and international order.

And if we are to use the next three years learning the lessons of the century that has passed since 1926, where better to start on the task than here in Llŷn and on the platform provided by the University of Swansea? And how better to conclude than with two poems by Williams Parry, the first to Y Gwrthodedig – the Rejected One:

Hoff wlad, os medri hepgor dysg,

Y dysgedicaf yn ein mysg

Mae’n rhaid dy fod o bob rhyw wlad

Y mwyaf dedwydd ei hystâd.

(Beloved land, if you can do without the learning

Of the most learned in our midst,

You must among every country

The most blessed of all.)

And again, from Y Cyn-ddarlithydd, the Former Lecturer:

“Y Cyntaf oedd y mwyaf yn ein mysg

Heb gyfle i dorri gair o gadair dysg

Oherwydd fod ei gariad at ei wlad

Yn fwy nag at ei safle a’i lesâd.”

(The first was the greatest among us

With no opportunity to speak a word from the chair of learning

Because his love of his country

Was greater than of his position or his well-being.)

Diolch yn fawr.

Editor’s Note

This is a translation from Welsh of the lecture delivered by Dafydd Wigley at the 2023 National Eisteddfod at Boduan near Pwllheli. Where possible, previous received English-language versions have been used in rendering direct quotations, notably the translation by Dr Bruce Griffiths of Saunders Lewis’ Egwyddorion Cenedlaetholdeb – Principles of Nationalism published by Plaid Cymru in 1975 on the occasion of the party’s Silver Jubilee. I have translated other passages. I have also made use of the work of D.Hywel Davies and Emyr Williams. I am grateful to them, and also to D.Hywel Davies for his practical help.

Dafydd Williams

Sources

The Welsh Nationalist Partty 1925-1945: A Call To Nationhood. D.Hywel Davies (1983) Cardiff. University of Wales Press.

Saunders Lewis: Letters to Margaret Gilcriest. Edited by Mair Saunders Jones, Ned Thomas and Harri Pritchard Jones (1993) Cardiff. University of Wales Press.

Egwyddorion Cenedlaetholdeb – Principles of Nationalism. Saunders Lewis (1975) Plaid Cymru. Printed originally in 1926 by Ryan Jones, Argraffydd, Machynlleth.

The Social and Political Thought of Saunders Lewis, Emyr Williams. A dissertation submitted at the School of European Studies, Cardiff University, in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Cardiff University. June 2005.

https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/54521/

Social and political thought of Saunders Lewis. -ORCA (cardiff.ac.uk)