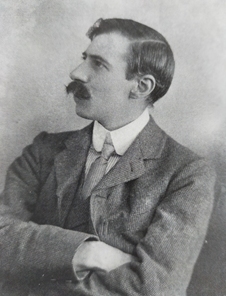

The history of the great poet, T.Gwynn Jones (1871-1949)

Review of the Welsh language biography ‘Byd Gwynn’ by Alan Llwyd

We have good reason to be grateful to the poet and author Alan Llwyd, who was brought up in the Llŷn peninsula and now lives in Morriston. His awdl, a poem in strict metres on the subject Llif (stream, or flow) ensured that the chair could be awarded this year, providing a real climax for the successful Llŷn and Eifionydd National Eisteddfod.

By now Alan Llwyd has established himself as one of Wales’ outstanding poets and writers. His output is astonishing, both in quality and quantity , and includes a number of detailed biographies of Welsh poets, among them T. Gwynn Jones.

Today people remember T. Gwynn Jones as one of the leading poets of the twentieth century but he was much more – for decades a hardworking journalist, novelist, critic and adjudicator as well as a translator and linguist. And a committed pacifist and a fiery nationalist.

Alan Llwyd paints a detailed picture of his life from his upbringing in Denbighshire as son of a struggling tenant farmer. Although his family’s straitened circumstances ruled out university, Gwynn’s sheer talent ensured a career as a journalist in Welsh and English newspapers such as the Cymro and the North Wales Times. But he also contributed substantially to the cultural life of Wales. At the age of 17 he published a poem in Y Faner in support of Welsh people’s fight against being forced to pay tithes to the established Church of England, and from then on he would occupy a key role in the literary life of his country.

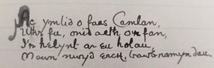

In 1902 he carried off the Eisteddfod Chair with his poem Ymadawiad Arthur, making purposeful use of the complex Welsh mode of cynghanedd to create a special effect; as Alan Llwyd explains, “not throwing consonants idly around without regard to the meaning of the words “. In this respect, he was very different to many other poets , such as Hwfa Môn and Dyfed; and before long Gwynn would find himself in the middle of a fierce debate about poetic standards. Critics would accuse him of resurrecting antiquated words that no-one understood, but Gwynn was more than ready to stand his ground and use his jounalistic skills to fight for rasising the standards of the Welsh language and experiment with new measures.

Cynghanedd, according to Gwynn, was the learned term for what ordinary people called a ‘cwlwm’, a knot or link. As a schoolboy he came to know these links by ear before learning the rules, and coming to love them.

He succeeded in surmounting every obstacle, moving from his ill-paid journalistic career to become a cataloguer and biographer in the National Library in Aberystwyth, and in 1919 a lecturer, and finally Professor of Welsh Literature in Univerity College, Aberystwyth. Alan Llwyd also records Gwynn’s marriage and happy family life.

Gwynn became an accomplished linguist and translator in a number of European languages, and especially the Celtic languages. He had learnt the Breton language before the visit in 1904 of the Celtic Congress to Caernarfon, and Gwynn played an active role as a member of the local organising committee. Later on he set out to master Irish, seriously considering academic posts in Ireland.

Throughout his life T.Gwynn Jones was a convinced nationalist, but it is interesting to explore exactly what that meant during the course of his life. Gwynn’s father was a keen Liberal: he was forced to leave the farm at which he was tenant because of his opposition to the Tories during th ‘tithe war’ in rural Wales. The young Gwynn also supported the Liberal cause, enthusiastically so during the period in the 1890s when the Cymru Fydd movement was campaigning for self-government. In 1903, he composed a poem in Welsh praising David Lloyd George, ‘our Dafydd of silver tongue, and a heart of fire’.

Disillusion with the Liberal Party followed the failure of Cymru Fydd and the support of many Liberal leaders for the First World War. Gwynn was a lifelong convinced pacifist, and was profoundly disappointed by the ‘dogs of war’, politicians and ministers of religion who urged young people to go to their deaths in the slaughter. As a socialist as well as a fervent nationalist, by 1918 he was attracted to the Labour Party, telling a close friend that he had (like DJ Williams) joined the ILP.

However, there was no question whose side he was on when the Easter Rising took place in Ireland in 1916: if England had the right to fight, then so did Ireland, he said.

In 1923, Gwynn chaired a meeting of the ‘Tair G’ (the three Gs, Y Gymdeithas Genedlaethol Gymreig or The Welsh National Society), one of the meetings that would lead to the formation of Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru. It is not known what was his reaction to the suggestion voiced at that meeting by Saunders Lewis to set up an ‘army’ of volunteers who would conduct military drill – it is unlikely he would have been in favour, and the idea found little support at the time. Could that be one reason why, curiously, there is no evidence that this convinced nationalist ever joined the nationalist party launched in 1925. Indeed, some years later, he would admit that his friendship with one poet had cooled because of the latter’s support for Plaid Cymru.

By 1943 however, Gwynn was prominent among those who nominated Saunders Lewis as Plaid Cymru’s candidate in the University of Wales by-election, even though he was running against W.J. Gruffydd for the Liberal Party. Gruffydd had been a close friend of Gwynn’s since his youth.

A great poet, and an emotional and complex character, T.Gwynn Jones stands out as a leading figure in the history of Wales, and his story is well worth remembering.

Dafydd Williams

From the Plaid Cymru History Society Newsletter Autum 2023