Hundreds of people – from Ireland, Scotland and every part of Wales – attended the funeral of the author, journalist and noted nationalist Ioan Roberts in Chwilog, Gwynedd on Saturday 4 January 2020.

Ioan played a key role inthe work of Plaid Cymru from the 1960s on – not as candidate or lead official but as a talented, creative and prolific writer. He was responsible for most of the election literature of former Plaid president Dafydd Wigley, who also pays tribute to his sense of humour – alway seeing the amusing side in events, circumstances and people that most of us wouldn’t have spotted.

Ioan played a key role inthe work of Plaid Cymru from the 1960s on – not as candidate or lead official but as a talented, creative and prolific writer. He was responsible for most of the election literature of former Plaid president Dafydd Wigley, who also pays tribute to his sense of humour – alway seeing the amusing side in events, circumstances and people that most of us wouldn’t have spotted.

Here you can find copies of the tributes paid by the Chairman of Plaid Cymru, Alun Ffred Jones, former General Secretary Dafydd Williams, the Archdruid Myrddin ap Dafydd – a tribute that includes a pearl of a poem to Ioan and personal memories on behalf of the family by Ioan’s daughter Lois. There is also a recording of the funeral service led by the Reverend Aled Davies.

Cymdeithas Hanes Plaid Cymru’n extends its condolences to Ioan’s family and thank them for their help to remember the career of one of the great characters of our national movement.

Alun Ffred’s eulogy to the late Ioan Roberts. Siloh Chapel, Chwilog, 04/01/2020.

Family, friends.

The large congregation here today in Chwilog is testimony to the respect we had for Ioan and to his gentle but mischievous personality. I am sure that as a family you sense the sympathy wrapping around you in your grief and ‘hiraeth’. Thanks for the honour of saying a few words on this sad occasion. I have been warned by Alwena to be brief and to be decorous. Therefore some stories will be kept for another time. Myrddin has captured much of Ioan’s essence in his excellent poem and we have heard Ioan’s way-with-words in the excerpts he read.

So, Ioan Roberts; Ioan; Io Mo. The day after hearing the sad news I went to visit Dora, Wil Sam’s widow. (Wil Sam was a writer, dramatist and folk hero to Ioan’s generation and a close friend and collaborator.) On the table in front of her was Ioan’s latest book on Geoff Charles, a Christmas present from Ioan to her. She mentioned how he used to visit her on the occasional Saturday. “And I’ll tell you why,” she said.”Because I had told him once, after I lost Wil that I felt his absence most keenly on Saturdays.” That was typical of Ioan, being loyal and supportive.

And, of course, there were similarities between the two men; both of them were skilled wordsmiths; both fond of telling tall tales; both evergreen in spirit and neither had ever completely lost the ‘boy’ within. In 1989 Ioan received an invitation to produce the television series Hel Straeon – (Telling/Gathering Tales) a series which Wil Aaron had already started as part of his ‘empire’ at Ffilmiau’r Nant. The title Hel Straeon happens to encapsulate much of Ioan’s life.

In his professional life,- after one false start – his profession was gathering and telling stories as a journalist, programme editor and in his wonderful books; and he did so in clear plain Welsh. And, socially, as all of you know, he was never happier than when telling stories about people and their foibles; a wonderful memory for details and quotations even in the early hours when every sane person was abed. Pengroeslon, Rhoshirwaun was where it all began for him and his sister Kate and though he left to go to college and to find work he actually took Pen Llŷn with him in his language, its sing song lilt and his gentle nature.

And though he was glad to return and contribute to the community- and the Plas Carmel project was close to his heart and will benefit from your contributions today – there was nothing parochial about him. His politics had a national and international dimension as his close ties with Scotland and Ireland proved. The interest in Ireland started early on and in his youth a group of friends were frequent visitors to Dublin and the West. He used to tell a story – one of dozens – about him and a friend, Wil Coed, hiring a car to explore the West of Ireland. If they exceeded the agreed mileage there would be an added fee payable. Somewhere around Dingle funds were getting low but the mileage was going up so they hatched a plan to hoodwink the hiring company by reversing the car round the Dingle peninsula to wind back the mileage clock! The experiment was not a success. The interest in Ireland, indeed the obsession, lasted of course and he became very knowledgeable about the people and the politics of the island.

Anyway, after attending school at Llidiardau and Botwnnog the details about his higher education are a bit sketchy. But he went to Manchester University to study Civil Engineering. In his first week he met the typhoon known as Dafydd Wigley and so began a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives. Soon they were sharing a flat, an unfortunate arrangement academically speaking; according to Dafydd far too much time was spent reciting poetry; Ioan reading Yeats to Dafydd and he in turn reciting Williams-Parry back. You are welcome to believe that story if you wish. Anyway, Dafydd left the college with a degree – and Ioan simply left. Years later when he was interviewing the estimable Sir Thomas Parry, the knight asked Ioan which university had he attended and which course had he followed? Ioan told him the truth. Tom Parry looked aghast and said in his booming voice,” What an awful thing to happen to a man!”

Awful or not, Ioan obtained employment looking after the roads and bridges of Montgomeryshire and getting to know the good folk of the county he came to love. He shared a house with a group of sober and upstanding young men ( pause for tittering). Later he was promoted to oversee the sewage systems of Shropshire; of the two responsibilities he thought the first had more dignity. Sometime during this period a group of nationalistic students came from Edinburgh to Cardiff to a rugby international match. Ioan and some friends met them and though he was dissuaded from boarding the bus back to Scotland, new friendships were struck and a great deal of toing and froing between the respective countries began. Ioan, and later Alwena, came to know Morag, who is here today, and others who have become members of the extended Roberts family.

Of course the most important thing that happened to Ioan in Montgomeryshire was meeting a young lass named Alwena while out canvassing for Teddy Millward, which proves the value of canvassing for Plaid Cymru, perhaps. In time a successful duet was formed, one with a voice like an angel and one with no voice at all. He had already written a few articles for the Welsh language weekly Y Cymro about rural villages in the county and when the opportunity arose he joined the staff. That was the start of a new career and learning his trade as a journalist. They were trained to write stories simply and effectively and he ended up as the chief reporter and a very skilled and influential writer. As Robin Evans, a fellow journalist and friend, said of him, “The contents came first for Ioan; the style merely served the story.”

They moved to Penycae, Wrexham, in the wake of Alwena’s developing career and came to know a very different society – an industrial and post industrial community and a new set of friends. Three years later the head of news at HTV, Gwilym Owen, headhunted him to become the editor of the daily Welsh language news programme Y Dydd . They moved, not to Cardiff but to the less fashionable Pontypridd and made new friends, both Nationalists and Socialists and at least one Communist! There is no record of him befriending a Tory however. There were two news programmes broadcast by HTV, Y Dydd and Report Wales but only one newsroom and there was a bit of tension between the rival teams , partly because the Welsh programme was aired before RW at six o’clock . But Ioan and the RW editor, the wonderfully eccentric Stuart Leyshon of Sketty, got on like a house on fire and Ioan won over the cynical hacks with his professionalism and his good nature.

Of course Ioan was not what you would call a ‘company man’ and the relationship between him and senior management was not always cordial. I remember him being called in to be given a ticking off following an unfortunate incident in Dublin after a rugby international. In the meeting he was reminded that wherever he was and at all times, he was an ambassador for HTV! The message fell on deaf ears I’m afraid.

Amazingly, despite his responsibilities, during this period he edited both Plaid’s journals Y Ddraig Goch and the Welsh Nation, often burning the midnight oil to meet deadlines. And when Gwynfor threatened to fast to death over a new Welsh Language channel I remember Ioan asking us as journalists what our response should be if the worst scenario came about? He had no difficulty being impartial as an editor but first and foremost he was a Welshman and a nationalist.

Ironically, the creation of S4C brought Y Dydd to an end and he lost his job. He was hurt and it was a difficult time for both him and Alwena. Deliverance came once more in the shape of Gwilym Owen, who had had a rough time himself but had been appointed as head of news at Radio Cymru. He employed Ioan as an editor and producer on news programmes. Ioan always had a deep respect for Gwilym as a hard working news chief.

Escaping to Ireland for holiday breaks with the family was important. Galway, County Clare and, more often than not, the Dingle peninsula and the small village of Baile an Fheirtéaraigh – Ballyferriter – in the Gaeltacht was journey’s end. New friends were made there, James and Treasa, Geri and the late Scott and their families; they are also by now an important part of the family and here today. From Scotland and Wales people were enticed there to talk, sing, make music and to drink the occasional glass. And Ioan’s response whatever the occasion was, “Isn’t it wonderful.”

Ioan and Alwena with their friend Morag Dunbar (centre) from Scotland, in the Dingle peninsula, Ireland

Mecca, as Myrddin described it, was a piece of land by Trá an Fhíona, the Wine Strand, looking out towards the Three Sisters headland. Reed covered rough ground, the nearest water tap half a mile away, a toilet and shop a good mile away and August storms whipping in from the Atlantic regular as clockwork. Ideal as a campsite! But for Ioan and many others the place was, and is, simply heaven.

One of the people Ioan came to know there was Bertie Ahern who, at the time, was Chancellor of the Exchequer (or the equivalent of). Early one rainy morning Ioan spotted Bertie taking his dog for a walk down by Wine Strand. In the afternoon he bought a copy of the Irish Times and was alarmed to read that the Irish punt was in trouble; “Punt in crisis” read the headline. Later in the day, presumably because it was raining, Ioan called in at Ui Chathain’s pub and was amazed to see the aforementioned Bertie Ahern there enjoying a pint. They were introduced and, just making conversation, he referred to the alarming headline and asked why the Minister wasn’t hotfooting it back to Dublin to deal with the crisis. Bertie’s dry answer was,” I never read the papers on holiday.” Years later with Ahern ensconced as Ireland’s Taoiseach, Ioan arranged a meeting between him and Dafydd Wigley in the Dáil, and we witnessed two wily politicians engaged in a lively debate.

The Pontypridd era came to an end with Wil Aaron’s phone call. Siôn and Lois were now part of the family and it was a big decision to move from a place where roots had been planted. But up they came and under Ioan and Wil Owen’s leadership Hel Straeon became one of the Channel’s flagship programmes. He also contributed ideas and scripts to the Almanac drama documentary series. The Hel Straeon period was a busy one and they travelled to America, to trace the history of the Welsh settlements, and made series in Ireland and Scotland. In a military camp on the island of Benbecula and running out of patience he introduced a pompous moustachioed Major to the presenter Lyn Ebenezer with the words, “Major Fairclough of the British Army, may I present Lyn Ebenezer who was a major too, in the Free Wales Army.”

The plug was pulled far too early on the series in one of those reorganisations that every institution feel duty bound to carry out. Once again Ioan was out of work and disgruntled. To be even handed Ioan could get tetchy and prickly at times. When Alwena was in the company you would hear the sharp command, “Shut up, Ioan.” He did get work on the current affairs strand Y Byd ar Bedwar but he deserved better. One of his little pleasures in recent years were the Robat Gruffydd tours with Meibion y Machlud ( the Sunset Boys) – a sort of international Last of the Summer Wine,- where socializing and compulsory jazz was enjoyed in Berlin, Donostia, Madrid and Lisbon.

But the latter years were very productive for Ioan the author. He had already edited a volume to celebrate the contribution of Elfed Lewis (a preacher, folk singer and choirmaster) and a book about the strange conspiracy case in Cardiff, Achos y Bomiau Bach ( the Case of the Small Bombs). He had also edited two volumes of the autobiography of Dafydd Wigley, who pays tribute to his sharp political opinion. For the publisher Carreg Gwalch he wrote Hanes C’mon Midffild and Pobl Drws Nesa ( Next Door Neighbours) – a busybody’s journey through Ireland – and Rhyfel Ni (Our War) about Welsh and Patagonian soldiers’ experiences in the Malvinas conflict. Myrddin ap Dafydd says that people talking about personal and sensitive feelings could trust Ioan to convey them truthfully and sensitively. Dylan Iorwerth called him “ an astute journalist and a good writer…behind the smile and the leg pulling he had a keen mind.”

For the Lolfa publishing house he edited three volumes of the photographs of Geoff Charles, his old co-worker on Y Cymro, spending weeks turfing through the files at the National Library. And the jewel in the crown, so to speak, was the beautiful volume on the life and work of the Magnum photographer, Philip Jones Griffiths. He was a slow worker according to Alwena but meticulous in his attention to detail. I can attest to that from the time he worked with me as Press Officer when I was an Assembly Member.

A book he has been wrestling with for a decade ‘Y Cylch Catholig’( the Catholic Circle) is about to be published. He became so concerned about it that he decided to retreat to a nunnery for peace and inspiration to finish it. He lasted one cold and silent night in a cell before beating a hasty retreat to the bustle of Pwllheli! There is more to be said, much more, but I can feel the shadow of his red biro hovering above the script.

Every parting is painful as we know but as a story teller surely he would appreciate that the setting in Porthdinllaen was striking, in the company of his family after a glass of wine at Tŷ Coch. So today we celebrate the life of a true and proud Welshman, productive and lived with zest, brimful of mischief, tears and laughter. It’s a story worth telling. Thank you.

Alun Ffred.

Io Mo

The magical land beyond the the sea that he saw from Rhoshirwaun

was a portal to longing. An island of dear friends;

the passion of their history and the craic of their congenial camaraderie.

The island where he could be free, Ioan being half and half Irish.

All his summers, his world was a merry haven along the sandy track,

a canvas roundhouse of convivial people, of poetry and song,

of wine and the legends by the Clann of the Dunes:

and he, the father, a strong current of love.

His peaceful haven was not a place for the petulant storms

of a homeland oppressed by the ebbing tide.

The unease was the same as he felt in Llŷn, but the wild landscape

soothed, far from arrogant pricks and their brash ambition.

His gentle haven was for the family – a sanctuary

beyond thoughts of furrowing the autumn toil,

the donkey-work to come, and the sweat of effort

as he nurtured the spring wheat in his favourite fields.

The harvest of his humour and storytelling captivated us all.

His voice, and his pithy quotes, gladdened every gathering .

His flair will be long remembered –

Master of the eloquent anecdotes.

Now the raconteur is put to rest,

A witty warrior has met his Culloden;

But there are so many vivid chapters to recall.

As we stand on the shore, his words are there, on the horizon.

Myrddin ap Dafydd

Ioan – Friend and Fellow Nationalist

I met Ioan for the first time in the mid 1960s, although exactly where and when I can’t be sure. But by the time I joined the full-time staff of Plaid Cymru in the winter of 1967, beginning with a month’s induction in the office in Stryd Fawr, Bangor, we were good friends. By then, Ioan had been an active Plaid member for a number of years – at least since 1959 when he went to Manchester University and shared a flat with Dafydd Wigley.

So for more than half a century Ioan played a valuable role in the ranks of the national movement. Throughout that time he was close to the heart of Plaid Cymru – not as a leading candidate or official but as a talented and creative writer and as a grass-roots member who was willing to put his shoulder to the wheel. He made his home in many different parts of Wales – in the rural Llŷn peninsula, in the Borders and also at the heart of the Valleys in Pontypridd – and everywhere he would contribute greatly to the work of the national movement and the Welsh heritage of the area.

As his lifelong friend, Wil Roberts (Wil Coed), secretary of Plaid’s Pwllheli Branch, says – Wales, Welshness and the Welsh language were Ioan’s concerns from an early age, “interpreting and presenting them to the Welsh people and his fellow Celts was his bread and butter, and he was to become one of the best and most entertaining communicators of his generation “.

When I first got to know Ioan, he was working as a civil engineer looking after the bridges of Shropshire County Council, and living a mile or so on the Welsh side of the border in Y Crugion (Criggion) in Montgomeryshire. I stayed there several times and enjoyed a number of jaunts around the county. As Wil Coed recalls, he helped Plaid Cymru’s election campaigns in Montgomeryshire. This included the design of a canvassing form suitable for recording results in rural areas where, more often than not, the names and addresses of electors were set out in alphabetical rather than geographical order – a real headache for election organisers as this information had to be rewritten in order to canvass from house to house and record the results systematically. I remember that we were still supplying these forms from Plaid’s National Office well into the 1980s.. They were printed in several colours – I don’t know whether Ioan was responsible for that detail but the headings were in his handwriting.

Ioan was among the crowds of spirited young people who flocked to Carmarthen in July 1966 to win Gwynfor’s historic victory. And as Wil Coed recalls he was campaigning with the same enthusiasm decades afterwards for Liz Saville Roberts in Dwyfor Meirionnydd and for Hywel Williams in Arfon in the December 2019 general election.

As well as being a dedicated nationalist Ioan was also by instinct a socialist, and I learnt that his father and the deep community roots of his family strongly influenced his view on life. When Alwena and he moved to Pontypridd, he made friends among trade unionists and nationalists alike and enjoyed the time he spent in Clwb y Bont among an interesting milieu of acquaintances. The couple settled in a house near the top of the hill in the Graigwen area, and during the Pontypridd by-election early in 1989, Ioan designed most of Plaid Cymru’s campaign literature.

Because of the nature of his work as a journalist – first for Y Cymro and later on for HTV and the BBC – his contribution to Plaid Cymru had to be kept confidential, although no-one could be in any doubt where his heart lay. And where job formalities collided with his dedication to the cause of Wales, there was no doubt which came first.

I remember one occasion during the early hectic days of one general election campaign – in 1987 I believe – when the press line rang in Plaid’s Cathedral Road headquarters: Ioan had just emerged from a meeting of correspondents where they had been briefed on how BBC channels in Wales would report the election. The plan was to allocate one slot to the ‘British campaign’, followed by another to the campaign in Wales. The consequence of course of such a scheme would be a substantial cut in any coverage of Plaid Cymru – and that was before taking any account of the huge coverage the other parties would receive on UK-wide channels broadcast in Wales. But inside information in good time is priceless – thanks to Ioan (and another correspondent who dropped off a copy of the offending memorandum by lunchtime) we were able to pile pressure on the Corporation to scrap the plan and replace it with one that was slightly fairer.

Ioan also worked as editor of Plaid’s Welsh-language newspaper, Y Ddraig Goch, although the obligations of his job meant that this role had to stay in the shadows. With his natural flair for vivid writing and a gift for identifying the newsworthy angle, he would always turn out a lively and interesting paper. Ioan was also responsible for most of the election material produced by the former Plaid leader Dafydd Wigley. Dafydd points out that he was blessed with an incredible sense of humour – seeing the amusing side of events and circumstances that most of us might not appreciate at the time. And he is dead right – it was always fun to be in Ioan’s company, as raconteur, listener and a true friend. He also had a photographic memory – an ability to recall details and reproduce them to good effect. No wonder he made friends everywhere, and kept them.

Ioan and Alwena attracted a number of people from Wales and Scotland who would cross the sea year after year to the Irish-speaking heartland of Corca Dhuibhne, the Dingle peninsula, meeting up with a crowd of Irish people during their summer holidays. Ioan’s Tir na n’Og lay beyond the town of Dingle or An Daingean – the village of Baile an Fheirtéaraigh (Ballyferriter). And in the company of Ioan and Alwena, and later on Siôn and Lois, we were all part of one big extended family.

Somehow or other, you were bound to come across interesting people in Ioan’s company. I went with him once to meet the scholar Donncha Ó Conchúir, former headmaster of the local village primary school and chairman of the cooperative enterprise. Another time when both of us were relaxing in Dic Macs, Dingle, who strode past with a big smile on his face but the Taoiseach, Charles Haughey, no doubt on his way to his personal holiday island, Inis Mhic Aoibhleáin. Later on, Ioan kicked himself for not placing his baby son Siôn, in Charlie’s arms and taking a quick photo – photography was one of his delights. He also got to know Bertie Ahern, later on Taoiseach himself – well enough for them to be on first name terms.

It was quite an experience to be in the company of a host of friends from Ireland, Scotland and from every part of Wales when the time came to bid farewell to our old friend. Ioan himself would have loved to be among us.

Dafydd Williams

Dad – Lois

Firstly, as a family, we’d like to extend our deepest gratitude for all the support that we have received during our bereavement. The messages, visits, tributes, and bara brith (!), have helped to slightly alleviate the grief we’re experiencing during this period of shock and sadness. We, the younger generation, have had the opportunity over the past few days to learn even more about dad, and we’ve almost been able to get to know him from scratch, through the memories of his friends and colleagues that have been shared with us. Sion and I were keen to take this opportunity to share a few stories of our own about dad, from the perspective of his children.

Well, it turns out that dad was quite a guy, wasn’t he?! Of course, Sion and I were already well aware of this, but at the end of the day, to us, he was just dad. Looking back, I appreciate that his patience with us as children was endless. He would often tell us about how Sion, when he was a little boy on their holiday in Scotland, would always insist that they stop the car each time he saw a hint of a loch, so that he could go out to throw stones into it. I know that dad gave in every time, and that he would pass the time by filming Sion on his camcorder. We have these videos still to this day. He’d do a lot of this – follow us around silently with his camera without drawing any attention to himself. We’re so glad that we still have these precious videos to treasure forever – thanks, dad!

It was going to Portmeirion, not throwing stones, that delighted me as a child. I’d better explain, although most of you will probably know this already already – but for certain parts of a year, mam would have an Eisteddfod or committee more or less every weekend. And so it would be up to dad to entertain us. Once, he took me to Portmeirion, and from then on, that was it. I’d insist we’d go there every weekend, until his loyalty card became completely battered. He’d let me play on the boat by the waterfront in my own little world for hours. He was probably bored to tears, but never ever did he make us feel as if anything else was more important than the both of us when we were with him. Dad’s patience never ended once we became adults either. He was always there for us, to listen and help with any problems, big or small, and tended to end a conversation with ‘you’ll be ok, you know’, with a solid pat on our heads. Only a month ago, Sion and dad had to venture to our next-door neighbour’s garden to dismantle Cadi’s trampoline when it flew, overnight, over the hedge during a storm. While Sion was ranting and raving when undertaking this task (it was massive to be fair, and by then it was dark!), dad remained completely calm, chuckling to himself every now and again. In every crisis, he could see the funny side. I think this completely sums up dad.

As a father, he was very mischievous. Once, he told Sion that he used to play for Arsenal. Poor Sion believed him and told everyone at school the next day. Sion has since admitted himself, that from seeing how dad kicked a ball, that he should have realised that it wasn’t a true story. Myself, I remember learning about shapes and angles at primary school, and asking dad, ‘what’s a polygon?’, and quick as a flash, he replied: ‘a dead parrot’.

Dad was a proud Welshman, and this would probably be at its most prominent during Wales matches. Sion described as he’d always well up during the national anthem, and when they went to the matches, instead of shouting ‘Wales! Wales’ like everyone else in the crowd, dad would yell ‘Cymru! Cymru!’ even louder. I had no idea that he did this until Sion told me the other day, and I really laughed because as it turns out, I do exactly same thing!

I cannot thank dad enough for teaching us about the importance of politics. I will miss our long conversations about current events, the future of Wales, Plaid Cymru… often these conversations would last hours, sometimes long into the night. On the night of the 2017 General Election, dad and I stayed up, and we both almost lost it – by the time Ben had won Ceredigion, the only appropriate word that comes to mind to describe how we felt (and behaved) is ‘hysterical’. I’m glad, in a way, that he will not have to endure the torture of seeing the devastating effect of Brexit on the Wales that he was so proud of.

Well, we couldn’t possibly talk about dad without also mentioning the legendary holidays that we took each August with the caravan. We’d always go to the Eisteddfod first, then off we’d go to Ireland. He used to tell us that he felt guilty at times that he never took us to more exotic places when we were growing up, especially when he learned that Tomos and his family holidayed in places such as France, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Italy etc. I suppose that on paper, a caravan holiday, on a completely exposed field in the south west of Ireland, with absolutely no facilities whatsoever, doesn’t exactly sound like the ideal holiday. But to us, that is just what it was. What better way to spend two weeks, than in the company of incredible friends that mam and dad had made years before we were even born, in a cosy awning, on a field that was idyllic when the weather was nice… but hell on earth if the weather turned. These holidays are such a valuable gift that we’ve been given by mam and dad and they have made us who we are today. We’ve been taught so much about the ability to socialise with people of all ages, and how to enjoy life. Thanks again, dad, and with a hand on my heart, I promise I’d never exchange our experiences for a holiday on the Costa del Sol.

I mentioned earlier that the Eisteddfod was first, before Ireland, again with the caravan. This would be a sort of pre-med before the big Irish holiday! But for Sion and myself, Eisteddfod with dad was a bit of a pain in the arse. People tend to associate mam with the Eisteddfod, don’t they, but with dad, if we let him get his way, and talk to everyone as he wanted to, we’d never see more than a quarter of the field! To entertain ourselves, we’d have to invent games such as ‘how many steps can dad take before he stops again to speak with someone else?” – the record? 2 steps!! We’d also be in stitches hearing people greet dad as ‘Io Mo’, and we had absolutely no idea why. Did he have a middle name? Morris? Morgan? Mohammed? As it turns out, no, it was just a catchy nickname. By now, I don’t think that he minded that people called him Io Mo, but when I was younger, I thought that he hated it. I realise now that he just didn’t like me and Sion to call him that. If I ever saw someone that I knew had worked with dad (and there are many of you!), I’d approach them shyly and say “I think maybe that you know dad…”, “Oh, who is he then?” “Ioan Roberts…” and on more than one occasion there would be no reaction for a second or two, then suddenly “Ooooh! You mean Io Mo!!”

It’s virtually impossible to convey how much he will be missed, but one important comfort is the fact that he became Taid to Cadi Shân. He took pride in his new role – and he took it seriously. I never thought I’d see him get up from his chair after such little persuasion, to dance around with her in the middle of the living room, or that he’d be so happy to wear her flowery hat on his head. If ever Cadi refused to eat when we were all around the dinner table, who do you think was the first, without fail, to start laughing? Well, of course, it was dad. And then we’d all completely lose it ourselves! It says a lot about the nature of our upbringing, and our relationship with our parents, that dad, mam, Sion, Sarah and Cadi were able to live happily under one roof – not an easy feat for any family, I’m sure you’d agree. I would also go home religiously, twice a week, to see them since moving to Caernarfon. This is such a tribute to the close bond we had. Being able to say that ‘Io Mo’ was our dad is a badge of honour that we will carry with us for the rest of our lives.

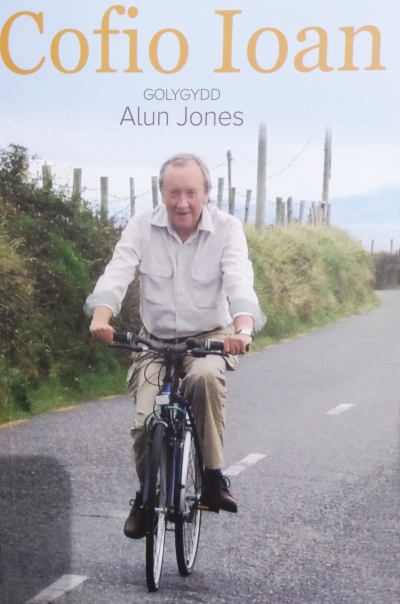

Ioan with his family

Recordiing of the Funeral Service on 4 January 2020

Ioan (left) as best man at the wedding of his cousin the Reverend Reuben Roberts, October 1959 – and the same people in the golden wedding celebration in October 2019: Ioan Roberts, Reuben Roberts, Aelwen Roberts a Dr Helen Wyn Jones