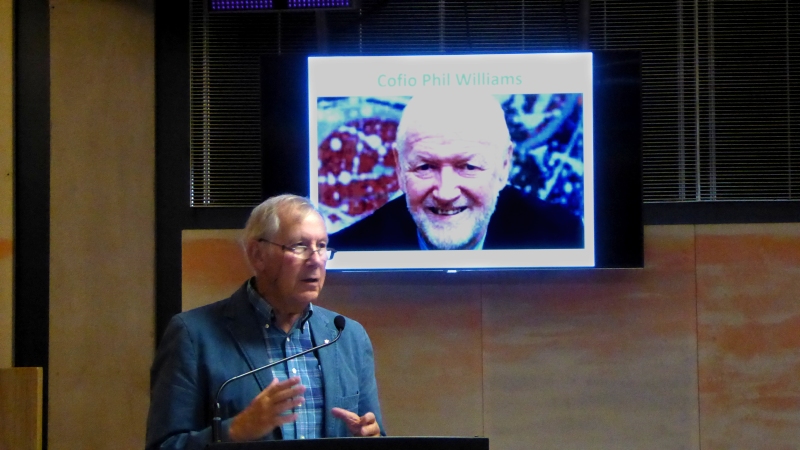

At a special meeting in the Cardiff National Eisteddfod on Thursday, 9 August 2018, Plaid Cymru celebrated the life of the late Professor Phil Williams, the party’s candidate in the Caerffili by-election fifty years ago.

At the meeting, organised by the Plaid Cymru History Society, tributes were paid by Dafydd Williams and Cynog Dafis with a contribution by Dafydd Wigley.

Remembering Phil Williams

A tribute by Dafydd Williams, Chairman, Plaid Cymru History Society

It is difficult to believe that fifteen years have passed since we mourned the loss of Phil Williams. And for my generation, it is also difficult to believe that a whole half a century has gone by since that historic by-election in the Caerffili constituency. We still await a worthy biography, and hopefully that will arrive in due course. But much has been written by and about this remarkable figure – so much in fact that the problem is what to leave out. It is good that Cynog Dafis is with us today to look at Phil’s contribution to our understanding of the importance of the environment, one of the great causes of his busy life.

Phil was four years older than me – he was born in Tredegar in the Heads of the Valleys in Gwent, and was brought up in Bargoed – a place, it was said, that boasted that second biggest coal tip in the world, although no-one was very sure where exactly was the biggest one! He was fond of tracing his descent on both sides of the family, his mother and father, from the Black Mountains of Carmarthenshire. This was important to him – because the story of his family mirrored the history of his country. His father’s parents started married life in Bryn Merched, a small upland farm near Llyn-y-fan. Years afterwards, Phil set out to find it, armed with an 1870 Ordnance Survey map – but all that was left was a pile of stones. His father’s family moved to a farm in the Rhymni Valley – a farm that depended on the vibrant economy of the local mining community. And something similar took place to his mother’s family – with her father moving from a job in a wool processing factory in the Llangadog area to work in the mines, ending his working life in Bargoed.

Phil was four years older than me – he was born in Tredegar in the Heads of the Valleys in Gwent, and was brought up in Bargoed – a place, it was said, that boasted that second biggest coal tip in the world, although no-one was very sure where exactly was the biggest one! He was fond of tracing his descent on both sides of the family, his mother and father, from the Black Mountains of Carmarthenshire. This was important to him – because the story of his family mirrored the history of his country. His father’s parents started married life in Bryn Merched, a small upland farm near Llyn-y-fan. Years afterwards, Phil set out to find it, armed with an 1870 Ordnance Survey map – but all that was left was a pile of stones. His father’s family moved to a farm in the Rhymni Valley – a farm that depended on the vibrant economy of the local mining community. And something similar took place to his mother’s family – with her father moving from a job in a wool processing factory in the Llangadog area to work in the mines, ending his working life in Bargoed.

So he grew up as one of three children, David, Phil and Jennifer, in the Rhymni Valley, where his father worked as a teacher and headmaster. His mother too worked as a teacher, having studied in the Coleg Normal in Bangor – and Phil would recount the sad story of how her fellow students poked fun at her local Welsh dialect, Gwenhwyseg, and how as a result she did not pass on the language to her children.

Phil attended the Lewis School, Pengam where his brilliance rapidly became apparent. I recently heard his brother David relate the story of how he gave a lift to Phil to attend an interview at Jesus College, Oxford – only for him to tell the panel that he really wanted to study science in Cambridge. Yet such was his performance that the Oxford dons held open a place for him, just in case! Thus it was that he went to Clare College, Cambridge, following his brother David – Phil to study science, as had his uncle, R.M. Davies, who was later Professor in the physics department in Aberystwyth – and it is interesting to note that Phil followed his uncle’s footsteps some decades later. In Cambridge he quickly came across using a computer – this was 1957, remember. And from then on, he would always be at the vanguard of technological development. I remember, sometime in the 1970s, being floored by his penetrating statement, “All you need’s a modem”! At the time, I had little idea what exactly was a modem or an e-mail – I believed that the Plaid office was leading the world with our brand-new cutting edge fax machine! And when Phil called, back in the sixties, for every house in Wales to have its own computer, people thought he was being unrealistic – today of course we take it for granted.

Yes, of Phi’s brilliance, there is no doubt. But he had much more to offer than brilliance alone. He also had a heart and a soul and a conscience – and fortunately for us, Wales became the focus of his aspirations. As one of the children of the mining communities, he had always taken an interest in the radical politics of the Valleys – and at the age of 16, he joined the Labour Party. In Cambridge, he co-authored the manifesto Socialism for Tomorrow, which called for the decentralisation of power from London by now he had seen for himself the intellectual chasm that lay between the Labour Party elite and the socialism of the working people of Wales.

Yes, of Phi’s brilliance, there is no doubt. But he had much more to offer than brilliance alone. He also had a heart and a soul and a conscience – and fortunately for us, Wales became the focus of his aspirations. As one of the children of the mining communities, he had always taken an interest in the radical politics of the Valleys – and at the age of 16, he joined the Labour Party. In Cambridge, he co-authored the manifesto Socialism for Tomorrow, which called for the decentralisation of power from London by now he had seen for himself the intellectual chasm that lay between the Labour Party elite and the socialism of the working people of Wales.

I doubt very much that Phil would welcome any comparison with the Apostle Paul! But there must have been some ‘Damascus moment’ in his career. Perhaps it followed the fierce debates about Welsh politics that took place between him and one of his fellow-students in Cambridge, the late Dr John Davies, who later became one of his closest friends. But despite those debates, and the seeds they planted, in 1959 he made his way to Caerffili to assist the Labour campaign in the general election. And there, he had a shock. There, he came across the Plaid Cymru candidate, John Howells. Here was a man brought up in Pakistan, non-Welsh speaking and working in the aerospace industry in California. John Howells blew away any remaining prejudice about Plaid Cymru and its vision for Wales. And after reading the Plaid manifesto, Free Wales, Phil Williams signed up as a member. He decided that there had to be a Plaid branch in Cambridge, which had two members to begin with – Phil appointed John Davies as secretary, and John appointed Phil as chairman!

From then on, science would have to compete with politics for his attention and his time. On the political front, he found the door of Plaid Cymru wide open, and no shortage of demand for his talent, energy and time. But science too was a constant source of attraction – and, I believe, sometimes also a place of refuge from political disappointments. in 1962, he married Ann Green who came from the Blackwood area in the next door Sirhywi valley – and a son and daughter, Iestyn and Sara, were to follow. Ann is a well-known artist who continues to exhibit her work – and Phil himself took a passionate interest in the arts, as well as playing a saxophone in a number of jazz groups over the years, and helping to set up the group Assembly Broadband in the National Assembly later on.

In 1964, he stood for the first time as Parliamentary candidate for Caerffili, a constituency he would contest for Plaid Cymru six times. This was the ‘Dr Phil’ I came to know as a fellow member of the Plaid Cymru Research Group, a new group led by Dafydd Wigley and himself. We used to meet in London, Phil travelling from Cambridge to join us. By now he had been appointed a Fellow in his old college, Clare, and breaking new ground in space science and helping to discover quasars.

Plenty on his plate in academia, therefore, but it was a turbulent time in Wales too, and he was determined to play a full part. We had Gwynfor in the House of Commons, but without the resources someone would consider normal these days. The plaid Research Group, Dafydd and Phil in particular, filled the gap to some degree – helping to uncover information and framing questions to put orally and in written form in Westminster.

And then, along came the Caerffili by-election. By now Phil had taken up a new post in Aberystwyth and I was on the party’s full-time staff in Cardiff. I had campaigned as a foot soldier before, including the key by-elections in Carmarthen and Rhondda West, as well as Abertyleri, but this was the first time for me to help organise a by-election from start to finish. And it was a by-election to remember – an impressive headquarters on the Twyn opposite Caerffili castle, a thorough canvassing system, an outstanding local team – and that motorcade, four hundred cars it’s said.

But what really makes Caerffili memorable is the way that Phil Williams went about the task of putting over the message – that Wales could run its own life as a free nation. There were public meetings in every corner of the constituency – and they were more like university seminars than party rallies, with people having the real opportunity to debate and pose questions. Phil came within 1,800 votes of winning, with forty per cent of the poll, a swing of 29 per cent, at the time the second greatest swing ever in the United Kingdom.

Fifty years on, it is important for us to recognise the far-reaching impact of that campaign. The Caerffili by-election pushed the government of Harold Wilson into moving ahead to set up the Commission on the Constitution, a process which led in the end to the devolution of power from London. Not that devolution was the target – Phil stressed the need for Wales to win full self-government, and he was quite happy to use the term independence. But without a doubt, following the by-elections in Carmarthen with Gwynfor, Rhondda West with Vic Davies and Hamilton in Scotland with Winnie Ewing – Caerffili gave a real push forward.

Phil played a major role in constructing one of Plaid Cymru’s most important publications ever, the 1970 Economic Plan for Wales, presented to the Royal Commission on the Constitution. At the core of the Plan was a robust analysis of the economy made by Professor Edward Nevin – an ‘input-output’ analysis that measured how different sectors of the economy impacted on each other. Nevin had already carried out an important study in 1957 that demonstrated that total taxes collected in Wales exceeded public spending, a study that had greatly impressed Phil before he joined Plaid Cymru. With the threats then evident to the coal and steel industries, a serious input-output study was clearly vital for any future economic strategy – and indeed Nevin himself was anxious for it to be used in just such a way by the Harold Wilson government. But no, it was ignored by the Labour government, who brought out a particularly flimsy document called Wales – The Way Ahead – and made Nevin see red!

Dafydd Wigley and Phil saw their opportunity, and persuaded Edward Nevin to allow us to use his work to provide an in-depth estimate of the potential unemployment facing Wales in the years ahead, given the problems of coal and steel. This was one part of the Economic Plan – defining the scale of the problem. It then went on to propose a pattern of growth areas, with new industries and the effective transport infrastructure they required. It was at the time a revolutionary approach that attracted widespread notice – I remember after a night spent by the Gestetner photocopier rolling out copies for the next day’s Press conference the thrill of seeing the front page lead of the South Wales Echo and its headline – ‘We’ll make you rich if you let us – Plaid Cymru’. And the satisfaction later on of listening to the praise it received from Lord Geoffrey Crowther, Chairman of the Commission on the Constitution and an eminent economist. Of course, London was deaf was the argument made. Coal, steel and agriculture lost thousands of jobs, creating exactly the knock-on damage predicted by Plaid Cymru – but without the developments needed to our infrastructure to counter the negative impacts.

About the same time as his work on the Economic Plan, Phil played an important scientific role in persuading Britain to join EISCAT, a European project that studies upper levels of the atmosphere. He was appointed as one of the directors, and later Chairman of the project in Kiruna, above the Arctic circle in Sweden where he was to spend a considerable amount of time. Once again, politics had to run alongside science – but again this experience greatly enriched his work for Wales. He would often compare the economic situation or public services in Wales with those of the Scandinavian countries. Kiruna was a former centre of iron mining in Sweden but thanks to the vision of that country’s independent government it had become a major centre for space science research. Visiting an exhibition on this transformation, Phil noticed that his home town – Bargoed – was cited as an example of how not to handle economic decline!

Once during the 1970s, Phil and I went on a journey to the South of France, Occitania – for him scientific work, for me a cheap holiday! Although the weather was not so great to begin with, and his car kicked up from time to time, we arrived safely at our first destination – an EISCAT observatory in a really inaccessible part of the Massif Centrale, miles from any bar or restaurant, but Phil in his element, discussing the latest discoveries with his fellow scientists – all of them young men wearing beards and jeans! Then it as on to Grenoble for a space science conference in the university, where Phil contributed to the lecture sessions and I was free to wander the city. Every now and then during the journey, the car would come to an abrupt halt – and Phil would jump out to take a photograph – not of a castle, or lake or mountain but a wall – he had a formidable collection of close-up pictures of bricks or stones in walls from all over the place.

Phil always demanded accuracy – in his politics as in his science – and he was never ready to accept alleged facts or figures without checking them through for himself. He was famously uncomfortable with a number of claims made by Plaid – for example, the amount of water exported by Wales which he worked out exceeded our total rainfall!

He would also keep every scrap of paper that seemed significant. I remember once during the mid-1980s, we had something of a scrap about the selection of a by-election candidate for the Cynon Valley – and everything depended on the status and representation of the party’s Women’s section – and whether it had been duly established in line with the party’s rules. It was Phil who came to the rescue, discovering the evidence from the 1950s somewhere in his attic! Perhaps because of this practice, he seemed to take with him multiple briefcases all his journeys, one for Plaid papers, one for his scientific work and so on.

Of course it was never easy to accomplish every task on his job list – and sometimes I would feel it necessary as General Secretary to lean on him for some policy draft needed for the Executive or National Council. More often than not, his voice would be heard on the phone with one of his frequent questions, “What’s the absolute deadline?”. And generally, my ‘absolute deadline’ would pass by, yet somehow or other he would never fail to produce the goods in time. And, naturally, his work was unfailingly of the highest quality, which was why Plaid Cymru would turn to him time after time.

I often find myself thinking, listening to the news these days, what would be Dr Phil’s opinion if only he were still with us? Brexit, for example. Phil was a Welsh European to the core, and while supporting Plaid’s line during the 1975 Referendum, he was glad when the whole thing was over. A year later, in an important speech to the Summer School in Lampeter, he stressed his support for the concept of ‘Europe of the Hundred Flags’, the idea of an association of free nations. He stood as a candidate for the European Parliament twice in Mid and West Wales in 1984 and 1989, and played a leading role in developing links between Plaid Cymru and parties representing the nations and regions of Europe. He saw clearly that we shared the experience of being internal colonies of the big powers. It is a pity that his vision was not shared by the establishment in London and the other capitals – It is unlikely we would face the prospect of Brexit and things would be very different in Catalunya and Scotland – and possibly in Wales as well.

Phil held a number of national offices with Plaid Cymru during his career, including those of Chairman and Vice-President, and there was talk on a number of occasions of him as a possible party leader. I do not believe he ever seriously desired such a role – apart from his career as a scientist, he never craved a role as a politician, although he acknowledged that election to the National Assembly for Wales was the greatest honour in his life.

Neither did he bother too much with his own image. The late Patrick Hannan told the story of how the two of them walked together to a university dinner in a grand hotel, Phil with a helmet on his head and pushing his bike. When they arrived, he parked the bike in the toilet, explaining that he often parked it there!

Phil was brought up non-Welsh speaking, although Welsh was the language of his ancestors on both sides of the family. But he learnt Welsh thoroughly, delivering a complex speech in Welsh on sustainable development in 2003. But spending his life in pursuit of excellence, he was aware that he could express himself the most fluently in English. That is why John Davies felt he was hesitant to use the other languages he learnt, languages that included Swedish, Norwegian, French and Russian as well as Welsh.

After fighting so many elections, it came as a surprise to win! But that is what happened in 1999, the annus mirabilis of Plaid Cymru, and Phil carrying the Plaid Cymru banner in the Blaenau Gwent constituency – with a fine campaign HQ in the centre of Tredegar – as well as standing second on the list in the South-east Wales region. The count in Ebbw Vale for the Blaenau Gwent seat went on late – and by the time Phil found his way to the regional count in Newport it was all over and everyone had gone home. Everyone, that is, apart from a caretaker sweeping up the floor, who informed him that ‘some Professor’ had won a seat but had failed to show up for the announcement. And thereafter Phil liked to say how that was the way he heard confirmation that he had won an election – after four decades of campaigning!

So for the first time he became a full-time politician, although he would spend most Mondays lecturing or in the laboratory in Aberystwyth. Perhaps the National Assembly was not the natural environment for him and his style of communication, although I am sure that Westminster and its crude ‘knock about’ would have appealed much less. But his knowledge and his approachable style made a deep impact on his fellow-Members, so much so that he was chosen as Assembly Member of the Year for his work – this in the Assembly’s first year by Channel 4 and the Western Mail. Fortunately his speeches and major interventions have been published in a handsome volume, thanks to Gwerfyl Hughes Jones, and this collection stands as proof positive of the care and ability that Phil invested in everything he did throughout his life.

Membership of the National Assembly opened up a whole new treasure trove of information, something he used with great skill to expose the way the Treasury in London pocketed European funds instead of passing them on to Wales. Once again his partnership with Dafydd Wigley proved crucial and the effects far-reaching – including toppling Alun Michael from his post of First Secretary and – still more important – forcing the Chancellor Gordon Brown to accept transferring European money intact to Wales, all £442 million of it.

Somehow in the middle of this hectic period he found time to contribute a masterly study of Welsh scientists, another of his favourite topics, to the Encyclopaedia of Wales. And he was equally as passionate in his support for the arts in Wales – it’s worth reading his speech to the Assembly celebrating all the artists Wales has produced and calling for the establishment of a gallery for contemporary arts with regional branches.

I was disappointed to hear he intended to give up his Assembly seat in 2003. Science was exercising its gravitational pull once more – and Phil planned to spend more time on his space science research. There is no doubt he felt more at home with his fellow scientists. Not that every scientist is a saint and every politician a sinner, he once remarked. “But there is a different attitude towards truth. If a scientist deliberately presents false data, that scientist has ruined his or her reputation for life. But politicians do it all the time”

And yet – a short while before his untimely death, he was planning to work as a part-time research assistant to new Assembly Member Alun Ffred Jones – and so continue to combine two action-packed lives.

His death, at the age of just sixty-four years, came as an enormous blow to people in many walks of life. Today we can only give thanks that he was ready to give so much for the cause of Wales.

This is an extended version of the address to a meeting of the Plaid Cymru History Society delivered in the Cardiff National Eisteddfod, Thursday 9 August 2018

Select Bibliography

‘Voice from the Valleys’. Phil Williams. Plaid Cymru (1981)

‘The Story of Plaid Cymru’. Dafydd Williams. Plaid Cymru (1990)

‘The Welsh Budget’. Phil Williams. Y Lolfa (1998)

‘Pam y dylai Cymru gael Hunanlywodraeth? / Why should Wales have self-government?’ Phil Williams. Plaid Cymru (1997)

Professor Phil Williams (Obituary). Meic Stephens. The Independent. 13 June 2003

‘Phil Williams (1939-2003)’. Cynog Dafis. Planet, the Welsh Internationalist 152. Summer 2003.

‘Phil Williams: The Assembly Years’. Edited by Gwerfyl Hughes Jones. Plaid Cymru (2004)

‘Portrait of a Patriot’. Rhys Evans. Y Lolfa (2008)

‘Be’ Nesa!’ Dafydd Wigley. Cyfrol 4. Cyfres y Cewri 10. Gwasg Gwynedd (2013)