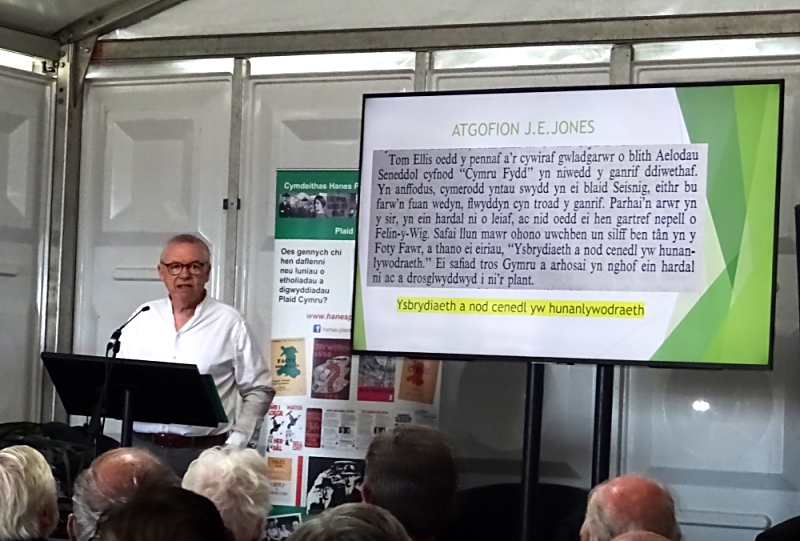

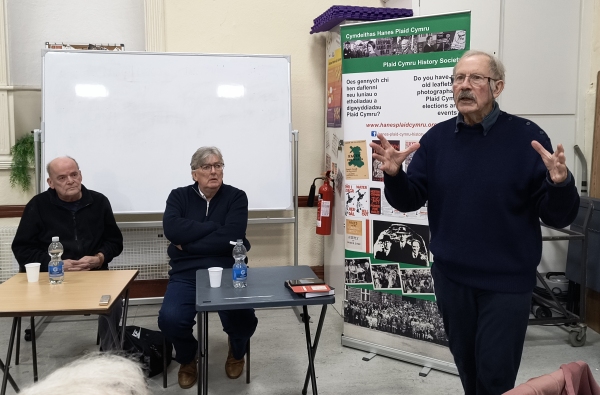

PLAID CYMRU HISTORY SOCIETY

WREXHAM NATIONAL EISTEDDFOD – SOCIETIES TENT

12.30pm, THURSDAY 7 AUGUST 2025

Translation of Lecture by Ieuan Wyn Jones

‘From Cymru Fydd to Plaid Cymru – The Journey’

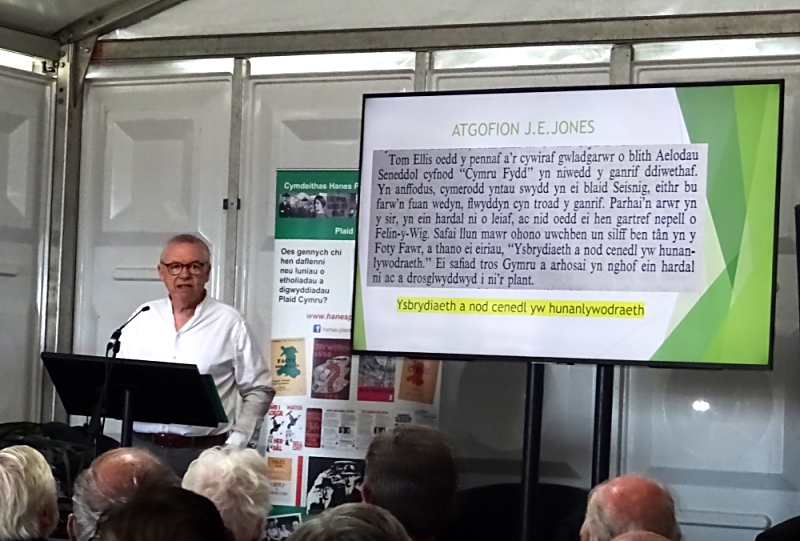

‘Tom Ellis was the greatest, truest patriot amongst the Members of Parliament during the “Cymru Fydd” period, at the end of the [nineteenth] century. Unfortunately, he accepted a position in his English party, and died shortly afterwards, a year before the turn of that century. He remained a hero in the county though, in our area at least, and his old house was not far from Felin-y-Wig. A large picture of him stood above our fireside mantelpiece at home in the Foty Fawr, and beneath it his words: “Self-government is the inspiration and aim of a nation”. His stance on behalf of Wales remained in our area’s memory and was passed on to us children.’

Excerpt from ‘Tros Gymru’ (1970), p. 21, by J.E. Jones (Plaid Cymru’s General Secretary, 1930-1962).

I begin this lecture with a quote from J.E. Jones’s book because it summarises the thoughts and feelings of some of the early leaders of Plaid Cymru, in the way that it considers the establishment of the Cymru Fydd movement in 1886 as the precursor to the party’s creation, and in their learning the obvious lessons from the failure of that movement. By far the most important lesson was that the principal failing of the nationalists of the Cymru Fydd movement – its attachment to the English and British Liberal Party – was to try to act from within that Liberal party. By 1925 the establishment of a Welsh National Party, that was completely independent of any other party, was a must. Griffith John Williams said in 1935: ‘It was essential to establish a Welsh Political Party’. Indeed, all its members had to sign a pledge to sever any links with other political parties in England and Wales.

But I’m running a little ahead of myself now. The story does not begin in 1886. We must go back to 1847. In many ways it is a critical year in our history as a nation, as that year a Report on the State of Education in Wales was published which soon became known as ‘The Betrayal of the Blue Books’. The intention of the British establishment in setting up the Commission which led to the Report was to try to make the Welsh more loyal to the state. The fact that the majority of Welsh people spoke Welsh and went to chapel led them to be a rebellious nation, with their protesting during the Chartist period and the Rebecca riots clear evidence of that. It was necessary to teach English to their children, to attract them back to the Established (Anglican) Church and thereby ensure a certain submission to their masters.

Reading parts of the Commissioners’ Report today clearly shows not only their lack of understanding of the Welsh nation, but also their arrogant, patronising attitudes towards Welsh speakers and their attachment to Nonconformity. The state of education in Wales was extremely poor, and the lack of teachers’ qualifications was to account for that. The standard of education for the common people in England was not much better, but of course the narrative that the Commissioners insisted upon meant that things were so bad in Wales due to a lack of English language skills. One example among many that populate the Report is the description of the teacher at Llandderfel British School. He understood English fairly well they said, but he spoke ‘with a Welsh idiom and not always grammatically!’.

The desire to teach English to the Welsh, and that at the expense of Welsh, ran side by side with the desire to bring them all back to the Anglican Church’s fold. But the way the Commissioners went about disparaging Nonconformity represented a stain on Welsh morals. Their position can be summed up by saying that for them the chapels were a den of immorality, and their ‘seiat’ meetings a place for women and men to court one another! The response of religious leaders, the only leaders the Welsh had at that time, was unanimous and vehement against the attack on their chapels. However, the response of many of them to the attack on the Welsh language was mixed and sometimes lukewarm.

We must remember the strength of the nonconformist chapels’ influence on the Welsh population. In the first half of the 19th century the leaders of the religious denominations were the natural leaders of the nation. Very few of the noble families, the big landowners and the like had any attachment to Welshness, the Welsh language or to Welsh identity. And up to 1840 relatively few of the religious leaders either were willing to dabble in politics – they were Tories and royalists. And then came the Betrayal of the Blue Books; and Lewis Edwards, Principal of the Calvinistic Methodist College in Bala, saying in 1848 that it was necessary to send ‘Principled Nonconformists to Parliament in every county and every borough throughout Wales.’

Many of the nonconformist political radicals came from among the Independent (i.e. Congregationalist) denomination, rather than from the Methodists. Gwilym Hiraethog for example left the Methodists and joined the Independents and his political radicalism can be seen at its most raw in Yr Amserau, the Welsh newspaper founded in Liverpool in 1846. The foundations of Yr Amserau were quite shaky at the outset, like many Welsh papers of the time. But when Hiraethog began to publish articles in a colloquial style under the title ‘Letters from the Old Farmer’ an audience of new readers was attracted. In these articles and in editorials he railed against the oppression meted out by landlords and began to support patriotic movements abroad. The two main figures who attracted his attention and support were Lajos Kossouth from Hungary and Giuseppe Mazzini from Italy.

Following the Hungarian Revolution in 1848 Kossouth was the country’s President for a short period, but the revolution was ultimately a failure and from then on he was a refugee who spent some time in Britain. Hiraethog praised him for his courage and his understanding of ‘the principles of true national freedom…’. Hungarians visited Hiraethog to thank him for his support. Kossouth came to Liverpool in 1851 and addressed a public meeting. Although there is no direct evidence that Hiraethog and Kossouth ever met, it is highly likely that it did happen during that visit.

And then we come to Hiraethog’s support for Mazzini, the nationalist who fought for the unification of Italy as a state. Mazzini also came to England as an exile and refugee on occasion, seeking the support of political radicals for his cause. One issue that attracted Hiraethog to Mazzini was his attack on Catholicism, something that pleased the radical Nonconformist no end! In correspondence between Hiraethog and Mazzini in 1861, Mazzini thanked the Welsh for their support and encouraged them to petition Parliament in order to put pressure on France to recall its troops from Italy. Hiraethog supported the fight of the Italians for their rights and independence, and there is concrete evidence that Hiraethog and Mazzini met a number of times in Liverpool.

Considering Hiraethog’s strong support for Kossouth and Mazzini in their efforts to secure independence for their countries, you would expect him to be equally as enthusiastic about similar rights for Wales. We can say with certainty that his support for the Welsh language was extremely strong, and he argued in favour of appointing judges who could speak Welsh to the courts in Wales. But there is no record whatsoever that he supported political freedom. And indeed he had little sympathy with the struggle of the Irish for self-government. Their attachment to Catholicism was an obstacle for him: in this respect he showed significant inconsistency though, as Kossouth was a Catholic!

Moving on from Hiraethog, it can be argued that the first person to support political rights for Wales in this period was Thomas Davis the Irishman of Welsh descent, in his book ‘Literary and Historical Essays’ published in 1846. He argued in favour of ‘a local senate’ in a federal form, as found in the American states. We have to wait for Michael D. Jones, Emrys ap Iwan, and later Tom Ellis, to raise the flag and emphasise political freedom alongside the fight for the Welsh language.

There was quite a debate between Michael D. Jones and Emrys ap Iwan about which of them was the first to advocate political rights. In a letter published in Y Genhinen in April 1892, at the time of that year’s general election, Emrys is adamant that it was he who first coined the term ‘ymreolaeth’ – autonomy – and furthermore he ‘was the first in Wales to argue for what the word means’. He can claim ownership of the word ‘ymreolaeth’, but what about his claim that he was the first to argue the case?

In his article on Religion, Nationalism and the State in Wales between 1840 and 1890, R. Tudur Jones says that Michael D. Jones was the father of modern political nationalism in Wales. Michael D. saw that there was a connection between national identity and political power. Although most of the nation’s religious leaders were quite happy that Wales was part of Britain, Michael D. argued that Wales was a minority cultural group in Britain, and English as the language of the majority a dominant language. In order for it to survive, the Welsh language would have to secure official status in the spheres of politics, education and the law. Once that happened, the result would be self-government rather than independence. Indeed there is very little, if any, reference to independence as the main goal of Welsh nationalists in the 19th century. The culmination of Michael D.’s argument was that Wales, like Ireland and India, should be considered colonies. He was the first in his time to see the need for Wales to manage its natural resources, water and minerals and use them for the nation’s benefit. That would create work and slow down the increasing migration of people from Wales to England and abroad. 19th century transport patterns tied Wales increasingly to England and through that was seen, in the words of Prys Morgan, ‘a system of economic inequality, emphasising to the Welsh that their economy was an inferior one, and mainly serving the needs of English Capitalism.’

By the 1870s a growth in Imperialist sentiment was seen in Wales, which coincided with rapid expansion in the number of British colonies and the state’s supposed prestige on the international stage. In this regard, Michael D. was rowing against the tide. He did not see any connection between imperialism and recognition of the rights of nations. He had a deep distrust of the British political establishment, stating that its intention was to eliminate the Welsh nation completely. Nevertheless he was aware of the meekness of many Welsh people as the relationship between Wales and England was so unequal, which in turn led to examples of quasi-paying homage.

The only other prominent figure who agreed with Michael D.’s minority position was Emrys ap Iwan. Emrys was a member of the Calvinistic Methodists, rather than an Independent like Hiraethog and Michael D. And when Emrys claimed that he was the first to campaign for self-government, Michael D. sent him a letter suggesting very subtly that he had influenced – possibly without his knowledge – his nationalistic beliefs!

Defence of the Welsh language was at the heart of Michael D. and Emrys’s nationalism. The easiest way for the state to assimilate the Welsh into one British nation was to eliminate the Welsh language. That, after all, was at the heart of the Betrayal of the Blue Books and the basis of the education laws that required English to be the only medium of education in schools. Aberystwyth University was founded in 1872, yet the Welsh language was not on the curriculum in its early years, and the Principal T. Charles Edwards was a member of Aberystwyth’s English chapel. This underlined the attitude of many of the leading members of religious denominations at the time, some of whom believed the Welsh language was likely to die out eventually. In this period therefore Emrys and Michael D. were very rare examples of people arguing in favour of fighting to keep the Welsh language, teaching it in schools, and making it the official language in courts. When Emrys appeared as a witness in a court case in 1889, he refused to give his evidence in English and insisted on speaking Welsh. There was turmoil in the court, and although the magistrates demanded that he give his evidence in English, he refused to do so. The case was adjourned and when the court reconvened there was a translator there. But since the defendant had admitted his guilt, Emrys’s testimony was not needed after all. Despite this, his stance received considerable attention in the Welsh press and Y Faner in particular was supportive of him.

Until 1886 then, these two voices were pretty much alone in their stance. And no elected politician was arguing in favour of national rights, either. Despite all that Henry Richard, the Apostle of Peace, did for Wales after being elected to represent Merthyr in 1868, he did not espouse self-government. And while a new set of Welsh Members of Parliament was elected in 1886, only one of them set out self-government as one of the main objectives in his leaflets. That was Tom Ellis, who was elected at the age of 27 to represent Meirionnydd. In his electoral address, he identified 5 areas that he would campaign for:

- Autonomy for Ireland

- Disestablishment of the Anglican Church

- A better education system

- Amending land laws

- Autonomy for Wales

Throughout his time as a Member of Parliament he saw three subjects – disestablishment, improving the education system, and land reform – not as individual measures, but as part of the fight for Welsh identity. Where did all this come from? He was at Aberystwyth University between 1875 and 1879. Not from there for sure, as the Principal persuaded him to join the English chapel in the town, and the main matters covered at the University’s debating society were British ones. He went to Oxford in 1879, and in his early days there he had little sympathy with the nationalist cause in Ireland. But little by little, over a period of four years, his attitudes became more radical and nationalistic.

There are many reasons for this, but let us concentrate on the fact that the ideas of Thomas Davis the Irishman and Mazzini came to his attention. As we saw earlier, Thomas Davis argued in favour of autonomy for Wales in 1846, despite being a voice in the wilderness at that time. Tom Ellis said in 1890, ‘Thomas Davis and Mazzini were my two political and nationalist teachers’.

So who was Thomas Davis? He was not one of the leading figures among the Irish national movement. Davis was rather a writer and poet, and one of the first editors of ‘The Nation’, paper of the ‘Young Ireland’ movement. ‘Young Italy’ was founded by Mazzini and his friends for Italian nationalists, and similar movements were established all over Europe. The English name for Cymru Fydd was in fact ‘Young Wales’. Davis wrote nationalist poetry, such as ‘A Nation Once Again’. He was a Protestant arguing that Protestants and Catholics should be taught together, and was in favour of Irish as the national language. His father was a Welsh doctor. He was known as a cultural nationalist, campaigning for self-government and arguing for a devolved Parliament in Dublin. It is easy to see how Davis would appeal to the young Tom Ellis, as there are romantic and cultural as well as intellectual elements to his nationalism.

Another person the young Tom Ellis encountered was the Irishman Michael Davitt. Davitt was a radical campaigner particularly on the subject of land, and was one of the founders of the Irish Land League. He was imprisoned in 1870 after being found guilty of illegal gun running. After his release he became a popular public speaker, arguing in favour of nationalising land in Ireland. Although he was a controversial figure at the time, a series of public meetings were organised for him in north Wales during the first half of 1886. Their organiser was Michael D. Jones, and a meeting was held in Blaenau Ffestiniog on 12 February. Tom Ellis welcomed the meeting in Blaenau Ffestiniog in an article in the South Wales Daily News. 3,000 listened to Davitt speak in Blaenau, where he declared that the Welsh should elect MPs who intended working together with the Irish nationalists led by Parnell, in order to reform land laws in Wales.

Davitt and Tom Ellis corresponded, both supporting greater co-operation between nationalists in Ireland and Wales. This is when Tom Ellis published a further article in the South Wales Daily News arguing in favour of self-government. ‘If Ireland secures self-government, isn’t it about time that Wales got the power to manage its own affairs?’ He supported the methods of the nationalists led by Parnell to secure their rights.

And as we have seen, Tom Ellis was the first candidate in a parliamentary election to include self-government as part of his electoral address, in 1886. But he was a very lonely voice when he was elected to Westminster that year. It was necessary to try to spread support more widely and as a result the Cymru Fydd movement was also established in 1886, and that in London. Its founders were Tom Ellis, the historian John Edward Lloyd, O.M. Edwards, Llewelyn Williams and others.

Its main aim was making the case for self-government. But there were also cultural aspects to the movement, and that was O.M. Edwards’s main interest in reality. It was a movement based outside Wales during those early years: its first branch was in London, and the second one was established in Liverpool. It was only in 1891, in Barry, that the first branch in Wales was set up, and more were then established in other parts of Wales, especially in areas where the Liberals’ party machinery was strong and where the secessionists amongst them were supportive. The first edition of the organisation’s magazine, also called Cymru Fydd, was published in 1888. Its editor was Thomas John Hughes or ‘Adfyfyr’, and he wrote the first editorial in January 1888, describing the magazine as ‘nationalist’. Initially it contained articles on the Welsh Liberals’ programme, land issues, disestablishment of the church, and improving the education system in Wales. The movement tended to stick closely to cultural and educational objectives until Tom Ellis and Lloyd George, who was elected following a Parliamentary by-election in 1890, gave it a political spin.

Between 1886 and September 1890, Tom Ellis was the main leader, arguing in favour of self-government, writing articles, delivering speeches and trying to pressurise his fellow Liberal members to follow his lead. But he faced very stony ground and was a lone voice amongst Welsh MPs. The older radical Welsh Members of Parliament, people like Henry Richard and G. Osborne Morgan, were quite content to argue the case for Disestablishment and land law reform, but were not happy to plead the case for self-government.

Tom Ellis decided he had to raise the tempo and try to prick the consciences of his fellow MPs. He went on a trip to Egypt in early 1890 where he succumbed to a period of serious illness. He was there for several months in an attempt to restore his health. In Luxor on St. David’s Day he set out in his diary the clearest sign yet of his political manifesto. Yes, it would be necessary to fight for disestablishment, a better education system and land reform. But in order to secure the nation’s unity, Wales would need its own Parliament, University and Temple.

At the end of the diary entry, at the age of 31 and aware that his health was precarious, he stated:

This is my vow today – to work until death to win Unity for Wales in the fullest sense of the word. May God give me strength to be faithful to this vow.

His quote from two stanzas of a poem by the romantic poet Shelley is an interesting one. ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ is considered to be the best political poem in the English language and was written in response to the Peterloo massacre in 1819. Two themes in Tom Ellis’ vision were ‘freedom’ and ‘unity’, and these can be seen weaving throughout Shelley’s work. When he refers to ‘Let the laws of your own land’ he recognises the right of every nation to have its own legal system, based on national sovereignty.

After Tom Ellis arrived home, and his friends in Meirionnydd realised how fragile his health was and that he was probably short of money, a testimonial was launched for him. A substantial sum of money, £1,075 (worth around £150,000 today) was raised and presented to him at a special meeting in Bala in September 1890.

In response to the presentation he delivered what his son T.I. Ellis called a ‘confession of faith’ (Cofiant II, p. 108). This was the most important and significant speech of his career as a politician. He realised that establishing a group of the Welsh Parliamentary Party in 1888 among some Members from Wales, under Henry Richard’s chairmanship, was unlikely to achieve much as there was no unity of opinion amongst them on the national question. The main themes of his speech were:

- Referring to the History of Wales, and the nation’s decision to stand up for its freedom and independence;

- Talking about the national awakening in the previous quarter of a century that had been strengthened since 1886;

- That the life of a nation depends on political action;

- That our main duty was to Wales;

- The need for national institutions such as a University of Wales, a National Museum, a National Library;

- Working for legislation supported by the men and women of Wales;

- Legislation would be a symbol of our union as a nation, it would be a voice for our nationality and fill our hopes as people.

No-one else among the Members of Parliament from Wales during the 19th century had defined so clearly what were the nationalist aspirations of this new set of leaders. Indeed, neither Michael D. nor Emrys ap Iwan had described nationalist aims so succinctly.

Tom Ellis therefore set out his stall, challenging others to follow him. ‘This is where I stand, who will come with me?’.

He wasn’t expecting cheers of approval for his call, though. He said at the end of his speech: ‘This is not the ambition of all of us’.

However, a few were willing to respond to the call. One of them was Alfred Thomas, Member of Parliament for East Glamorganshire. In this period he was close to Tom Ellis and had responded enthusiastically to the speech in Bala. He proceeded, with the support of Tom Ellis, to introduce a bill in the House of Commons on 15 June 1891, the National Institutions (Wales) Bill, with the intention of establishing a Wales Office, a University of Wales, a National Museum and a National Council (Parliament). It was tabled for a first reading but got no further. It was presented a second time in February 1892 and suffered the same fate.

There were more attempts between 1892 and 1896 to rekindle the enthusiasm of Cymru Fydd, this time under the leadership of Lloyd George: the years 1894 to 1896 are the most important in this. By that time, several branches of Cymru Fydd had been established in Wales. In that period numerous efforts were made to unite the Cymru Fydd alliance with the North Wales Liberal Federation in order to obtain commonality in the debate in favour of self-government. Lloyd George and Thomas Gee drove that bid for unity, as Tom Ellis had taken a job in Gladstone’s government. The next step was to try to unite the Federation in the south and the north of Wales. There were several attempts, and a decision was made to merge them in January 1895. But not everyone was happy about the merger, and its main opponent was David Alfred Thomas, MP for Merthyr. He oscillated between supporting the aims of Cymru Fydd and opposing them, but in the end he cast his lot with the hostile faction. Although some individuals were therefore willing to join in the call for a Parliament for Wales such as Alfred Thomas, David Randell MP for Gower, Herbert Lewis MP for Flint Boroughs, and David Lloyd George, they were actually quite isolated voices.

An attempt was made to re-organise the campaign in mid-1895 by appointing Alfred Thomas MP as Chairman of the Welsh (National) Liberal Federation and Beriah Gwynfe Evans as its Secretary. However, the attachment of many south Wales representatives to the idea of a united Federation was fragile and it all ended at a meeting held in Newport in January 1896, where the representatives rejected all attempts by Lloyd George to ensure the unity of the National Federation. Robert Bird, president of the Cardiff Liberals – and the owner of a coal tar distilling company – said that south Wales Liberals would not give in to Welsh ideas!

Some historians, perhaps a little superficially, come to the simple conclusion that a rift between Welsh-speaking rural Liberals and English-speaking urban and civic Liberals was the main reason for Cymru Fydd’s failure. But as John Davies argues in A History of Wales, there is more to it than that. Yes, there was a conflict between the rural and urban, but also between the radicalism, bordering on socialism, of Tom Ellis and the young Lloyd George and the conservatism of the Liberal leaders in the cities of south Wales. Assimilation between the northern radicals and budding socialists in south Wales would have been a much easier dovetailing exercise. In the end, the attachment of Lloyd George and others to the Liberal Party was strong, and the roots of Cymru Fydd’s ideas were neither deep enough nor broad enough to attract the Liberal Party to that fold en masse. Although Cymru Fydd dragged on for a year or two following the Newport fiasco, to all intents and purposes it was all over.

Although the efforts of Cymru Fydd’s leaders failed, it must be acknowledged that until 1886 nobody at a parliamentary level had been brave enough to raise the cause of Wales in this way. Tom Ellis was seen as the intellectual leader of the movement, and Lloyd George later as its campaign leader. It must also be remembered that the Liberal Party was in opposition when Tom Ellis was first elected, and indeed it was so for the greater part of his parliamentary career. Some historians argue that that party reached its peak early in 1886, and after it lost the election that year things were never quite the same. The party got a form of second wind at the beginning of the twentieth century, but after Lloyd George stepped down from being Prime Minister in 1922 it was thereafter in the political wilderness.

To what extent, however, was the Cymru Fydd movement a bridge that led to the establishment of Plaid Cymru in 1925 – and which led to securing an Assembly in 1997 and a Senedd in 2011? And why was there such a gap between 1896 and 1925?

Looking hastily at the 30 years, more or less, between the last fiery meeting of Cymru Fydd and the founding of Plaid Cymru, a few points deserve attention. One thing that is worth noting is the Act to disestablish the Anglican Church and create the Church in Wales in 1920. It took over 70 years for that campaign to reach its climax, which shows how difficult it was to secure any substantive change through Parliament in Westminster. Of all the campaigns of Cymru Fydd’s generation, disestablishing the church and creating the University of Wales are the only two that succeeded, though certain improvements in the education system were achieved, as well as the establishment of a Welsh Department within the Board of Education in 1907 and the Welsh Health Board in 1919. O.M. Edwards was appointed Chief Inspector of Schools in Wales where he fought to ensure the teaching of Welsh language in schools. However, English was the medium of education in those schools, especially secondary schools. In this period, some national institutions were also established, such as the National Library and the National Museum.

Two names worth noting in that 30-year period are E.T. John, MP for East Denbighshire between 1910 and 1918, and J. Arthur Price. John was a keen nationalist who introduced a self-government bill in Parliament in March 1914, a bill which did not go very far. John refused to join Plaid Cymru in 1925, remaining loyal to the Labour Party after having left the Liberal Party in 1918. Despite this, J. E. Jones claims that he turned to Plaid ‘in his later years’.

- Arthur Price was a barrister and became a keen nationalist, writing a number of articles on Wales for the journals Y Genedl Gymreig, Welsh Outlook and Y Ddraig Goch. He wrote a very critical article on Tom Ellis, accusing him of selling his principles once he took up a Whip’s position in Gladstone’s 1892 Government. Although a High Churchman, he was very supportive of Welsh causes and corresponded with Saunders Lewis.

It should be noted that three conferences on autonomy were held in 1918, 1919 and 1922 but little came of them. A Speaker’s Conference was held on devolution in 1919 but there was little agreement on the way forward, with the Speaker supporting the establishment of Higher Councils only for Wales, Scotland and England. In 1922, a bill was introduced to establish a Legislative Parliament for Wales by Robert Thomas, MP for Wrexham, but his efforts were unsuccessful. By the way, Robert Thomas was later the MP for Anglesey.

And that brings us to the founding of the National Party of Wales in August 1925, one hundred years ago to this very month. Since the successes of Cymru Fydd were relatively small, though not completely insignificant, and the attempts to argue in favour of Welsh causes in the Westminster Parliament were generally a failure, the new party rejected engaging with British politics. Although some, including J.E Jones, saw Cymru Fydd as a preparatory movement, others saw the need to distance themselves from the failures of that movement.

Saunders Lewis intended to show such distance by arguing that all links with British political parties should be severed. In Saunders’s opinion, nothing would come to Wales through the English Parliament. Lewis Valentine said ‘Some insist that the new party is synonymous with the old Liberal Party in a new form. But it cannot be denied more strongly than to say that there is absolutely no connection between it and the old parties’. D. J. Williams believed the new party should not express views on discussions in Westminster, saying ‘I am of the opinion that the Party should not interfere at all in the affairs of the English Parliament’. And as I have already mentioned, Griffith John Williams said ‘It was essential to establish a Welsh Political Party’. The early ‘Sinn Fein-ist’ position of the new Party therefore was that a seat in Westminster should not be taken, should they win an election.

However, as elements of realpolitik penetrated the Party’s consciousness after the 1929 election – when Lewis Valentine’s candidacy attracted 609 votes – the policy of isolation began to loosen its grip and party members insisted that it would be necessary to go to Westminster and accept that Parliament as a platform to debate the Welsh cause. And more mixed feelings towards Cymru Fydd’s efforts started to appear. Lewis Valentine originally dismissed the efforts of people like Tom Ellis in the early days of Plaid Cymru, and that quite deliberately. A real distance had to be created in order to justify the argument in favour of establishing a new political party, and that’s what we would have done too I feel sure. But as things settled, the views of some of the early members changed. Lewis Valentine reviewed a booklet published by Plaid Cymru in 1956, namely Triwyr Penllyn. The booklet contained three chapters on the contributions of Michael D. Jones, O. M. Edwards and Tom Ellis to Welsh life. The authors were Gwenallt, Saunders Lewis and Gwenan Jones. Gwenan Jones by the way was the first woman to stand in a general election on behalf of Plaid Cymru. Lewis Valentine says about the book that it is one ‘to put a bit of iron in the blood and a bit of steel in our spine’ in the fight against the drowning of Capel Celyn.

When Gwynfor Evans was chosen as Plaid Cymru’s candidate in Meirionnydd at the 1945 election, he saw himself in the lineage of Michael D Jones, R.J. Derfel and Tom Ellis. Y Dydd, a weekly paper in the Dolgellau area, made a comparison between Tom Ellis and Gwynfor, describing them as ‘Two young men with a gentle and loving spirit but nevertheless strong.’ Llwyd o’r Bryn compared Gwynfor’s stance on Capel Celyn as being like Tom Ellis’s for the ‘martyrs’ of the Tithe War. But to give a measured view of Gwynfor’s own opinion about Tom Ellis, he says in ‘Aros Mae’:

This (his decision to take up a post in Gladstone’s government) was the single act that did most to stop the development of an independent Welsh party, and therefore hinder the movement for self-government.

He then said:

It is easy to blame Tom Ellis now, but we must remember that Welsh nationalism was only young at the time, and that it was reasonable for him to believe that great gains could be made for Wales through working within the system.

So what do we now claim was the connection between the Cymru Fydd movement and the founding of Plaid Cymru at that meeting in Pwllheli on 5 August 1925, a hundred years ago this week? Considering the words of those who were at Pwllheli in 1925, very little. Their intention, at that time, was to create as much of a gap as possible between themselves and the leaders of Cymru Fydd. Otherwise, how could they justify establishing an independent Welsh party and the original policy of refusing to do anything with the Westminster Parliament? As far as I can see, Saunders Lewis did not change his opinion about Cymru Fydd at all in his lifetime.

But as things developed, and Plaid Cymru became a constitutional political party, the position began to change. If we take the words of J. E Jones, Lewis Valentine in 1956 and Gwynfor himself, they accepted that the establishment of Cymru Fydd in 1886, the first movement in centuries to argue for self-government for Wales, for creating Welsh institutions and increasing national awareness among the Welsh, had created the circumstances in which a Welsh party could then be established in the twentieth century. Given that Cymru Fydd’s hold on the nation was a fragile one, and that a relatively small number of Liberal Members of Parliament actually supported it – no more than about 5 at most – it was no wonder it failed.

But at least the discussion had started, and learning the lessons of Cymru Fydd’s failure was one of Plaid Cymru’s main objectives. It was a party with its loyalty to Wales and no connection to British parties. Although its growth was gradual, what is remarkable about it is that it has maintained its existence for a century and is now, according to some opinion polls, within reach of heading the Welsh Government for the first time.

Would Plaid Cymru have been established in 1925 if Cymru Fydd had not started the discussion? An impossible question to answer of course. All I wish to say is that the ideology and influence of Cymru Fydd helped crystallise the early philosophy of Plaid Cymru, and created the space for a new party to develop. And the failure of Cymru Fydd gave it the proof that the only way forward was establishing a fully independent party.

This is a task that I – and others taking part in today’s proceedings – did not seek and do not relish. It has been thrust upon us by recent events. The same can be said of everyone present this afternoon: we would prefer not to be attending the funeral of our friend, Philip Richards, and that he was still brilliant, bright and breezy among us – albeit of mature years. Yet we are where we are, and gather today to remember him; to share our knowledge of him – and, above all, to celebrate his life among us.

This is a task that I – and others taking part in today’s proceedings – did not seek and do not relish. It has been thrust upon us by recent events. The same can be said of everyone present this afternoon: we would prefer not to be attending the funeral of our friend, Philip Richards, and that he was still brilliant, bright and breezy among us – albeit of mature years. Yet we are where we are, and gather today to remember him; to share our knowledge of him – and, above all, to celebrate his life among us.