Thursday 10 August at the Eisteddfod in Boduan, a lecture was given by the barrister, author and academic, Keith Bush, who is a Fellow of Welsh Law at the Wales Governance Centre.

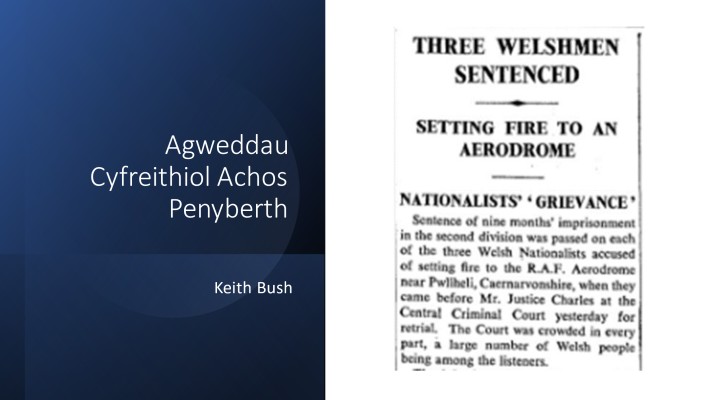

Legal Aspects of the Penyberth Case

(Lecture delivered by the author (as “Agweddau Cyfreithiol Achos Penyberth”) on behalf of the Plaid Cymru History Society at the National Eisteddfod, Boduan, August 2023)

The Penyberth case

On 19th January 1937, at the Old Bailey in London, Saunders Lewis, Lewis Valentine and D. J. Williams (“the Three”) were found guilty of property damage, contrary to sections 5 and 51 of the Malicious Damage Act 1861. They were sent to jail for 9 months. The basis of the charge was that the Three had “unlawfully and maliciously” burned buildings and materials on land that had been part of Penyberth farm near Penrhos, Llŷn but was now being converted into a Bombing School for the RAF. The action was part of a campaign against the Bombing School led by Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru (the Welsh Nationalist Party), of which the Three were leading members. Saunders Lewis had been its President for ten years, succeeding Lewis Valentine in that capacity. From the outset, the Three intended to take responsibility for the damage so that the ensuing court case could be used as a platform for the campaign and for the Party as a whole.

The social and political aspects of the Penyberth case have been discussed at length and in detail over the last eighty-seven years. But today I want to focus on its legal aspects, and in particular on the decision, after a jury in Caernarfon had failed to find the Three guilty of committing the damage, to move the case to the Central Criminal Court in London.

Sources

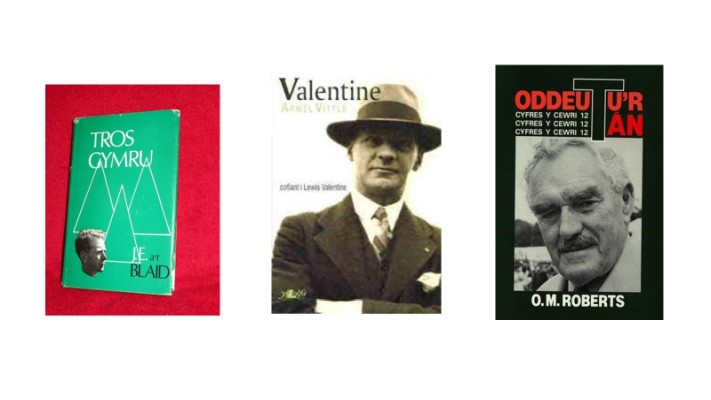

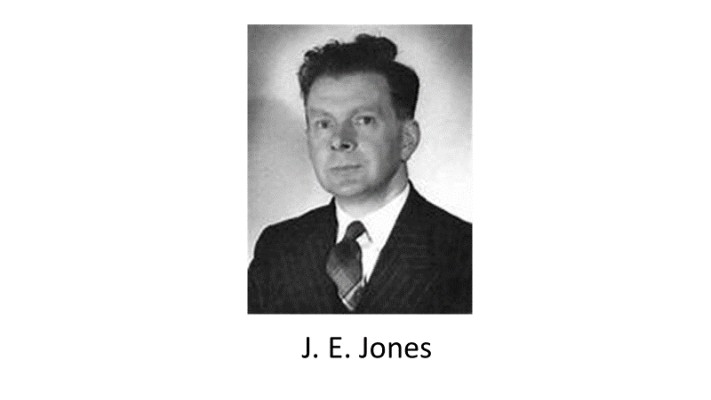

The story of the burning itself is told in a number of volumes, including “Tros Cymru”, the autobiography of J. E. Jones, then Secretary of the Welsh National Party, “Valentine”, a biography of Lewis Valentine by Arwel Vittle, and “O Gwmpas y Tân” the autobiography of O. M. Roberts.

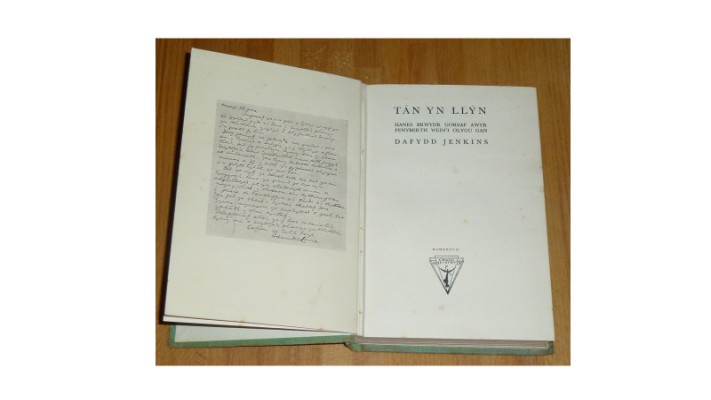

A thorough and detailed treatment of the court cases, is given in “Tan yn Llŷn”, published in 1937, by the 25-year-old barrister, Dafydd Jenkins (afterwards Professor Dafydd Jenkins) and I am deeply indebted to his work. But I have also been able to draw on sources about the case that were not available when “Fire in Llŷn” was written and which take us behind the scenes of the legal process.

The start of the process

The legal process began at about half an hour after two in the morning, Tuesday 8 September 1936, when the Three walked into the Pwllheli police office and asked to see the chief police officer for the area, Superintendent William Moses Hughes. When Constable Preston, the policeman on duty, asked what justified rousing Superintendent Hughes from his bed, Lewis Valentine replied, “Mae Penyberth ar dân” (“Penyberth is on fire”).

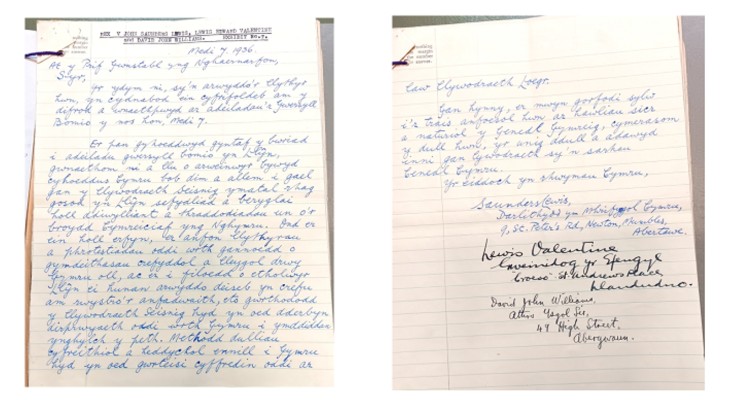

That was enough to cause the Constable to call the Superintendent. When he arrived, Saunders Lewis gave him a letter, signed by all Three, which “acknowledged our responsibility for the damage done to the Bombing Camp buildings this night, September 7.” (Note that the document is dated on the basis that the attack would take place before, and not after, midnight.)

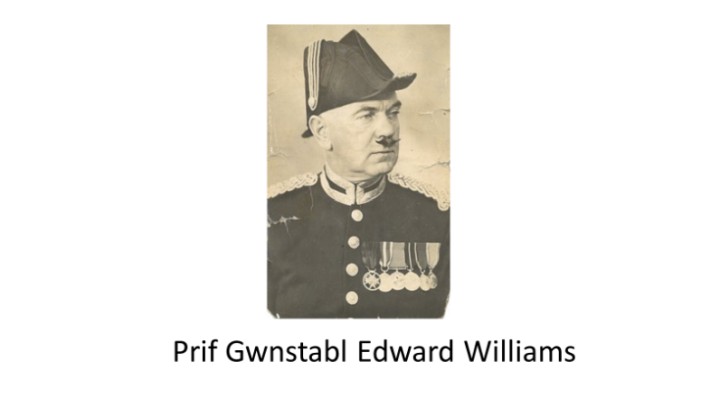

Chief Constable

The Three’s letter was specifically addressed to the Chief Constable of the Caernarfonshire Police, Edward Williams and after the Three had been arrested and placed in the cells, Superintendent Hughes telephoned the Chief Constable to inform him of what had happened. Chief Constable Williams receives little attention in the various histories written about the Penyberth case. But, as will become clear, his role in it was, in fact, an absolutely pivotal one. Edward Williams was a native of Llanllechid near Bethesda and the son of a quarryman. He started his career as a policeman in London, before returning to Caernarfonshire and working his way up to become head of police there. On the face of it, he was on good, even warm terms, with party representatives in Caernarfon, including J. E. Jones, whose office was in the town, and the Party’s solicitor, E. V. Stanley Jones, who had a practice there.

The Chief Constable was certain that Party officials were in over their heads in the attack on the Bombing School premises – a perception which was, of course, absolutely correct. Although the Three were the “A Team” that lit the fire, the buildings and materials hat were set on fire had already been doused with petrol by the “B Team” of four other Party members, led by J. E. Jones himself. But the Chief Constable did not have enough evidence to prove the direct involvement of other Party members in the act, which, not surprisingly caused him professional frustration. But his hostility and contempt for the National Party went far beyond that, and he already had a desire, when the opportunity came, to restrain its activities, as he explained to the prosecution lawyers. He described the Party as “a noisy clique (which) needs checking”. Membership included the kind of person the Chief Constable did not think very highly of: “It is mainly composed of Ministers of the Gospel, School Teachers, College Students and Members of the Nonconformist Body”. It had, in his view, no right to speak for Wales.

Something that still irritated him was what happened on St David’s Day 1932 when J. E. Jones and three other young men, two of them trainee lawyers, went to the top of the Eagle Tower at Caernarfon Castle, pulled down the Union Jack that was waving there, and raised the Red Dragon instead. He had failed, moreover, to find justification for prosecuting them. But that small success, in his view, was enough of a threat to the constitutional order that he brought the matter to the attention of the Security Service (MI5). He believed the incident had been an encouragement to the Party to risk direct action on a much more ambitious scale. When he received the news from Pwllheli, therefore, it did not surprise him. And he saw it as an opportunity to take that effective action against the National Party which he thought was necessary.

The Director of Public Prosecutions

Until the establishment of the Crown Prosecution Service in 1986, responsibility for carrying out prosecutions in the courts fell on local police forces, using either their own legal department or, particularly in rural areas, by employing firms of private solicitors. But there was a specialist central office in London, that of the Director of Public Prosecutions (or “DPP”), which was available to take over complex, sensitive or particularly serious prosecutions. Taking into account the political implications of what had happened in Penyberth, the Chief Constable arranged for his officers to contact, immediately, the DPP’s officers in order to warn them that he intended to ask them to conduct the and in order to seek their advice about the appropriate charge to bring against the Three. The DPP’s office advised that police should gather as much evidence about the incident as they could and to send them a full report as soon as possible. They should formally charge the Three, meanwhile, with an offence of doing damage to property contrary to section 51 of the Malicious Damage Act 1861, explaining to the local Magistrates, when the Three were brought before them, that more serious charges were likely to follow. The Three were represented before the Magistrates at Pwllheli, that afternoon, by E. V. Stanley Jones. The case was adjourned until the following week and the Three were released on bail.

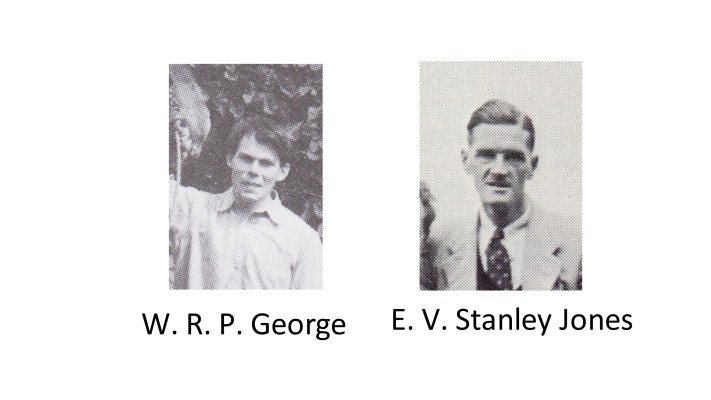

The Chief Constable sent the fruits of police enquiries, including statements describing the nature and value of the damage in detail, to the DPP’s office two days later, confirming, at the same time, his request for that office to take over the prosecution. He suggested, though, that it would be appropriate for the DPP to work with local lawyers. But he warned the DPP against seeking help from those lawyers who would normally carry out prosecutions for the police in the Llŷn and Eifionydd area, namely Alderman William George, brother of David Lloyd George, the former Prime Minister and Member of Parliament for Caernarfon Boroughs. The Chief Constable’s reason for avoiding William George was because, “his sympathies lean towards the Nationalists” – a trend highlighted, in the Chief Constable’s view, by a speech made by William George at a meeting of Caernarfonshire County Council on 8th September. He added that Wiliam George was also in partnership with his son, W. R. P. George, one who was “one of the four young men who pulled down the Union Jack from the flag pole at Caernarvon Castle on St. David’s Day, 1st March 1932; one of the others was Mr E. V. Stanley Jones, Solicitor, Caernarvon, who acts for the defendants in this case.”

The Chief Constable, in his letter to the DPP, stressed that he saw the attack on Penyberth as a real threat to law and order. He had heard that three other Party members had already been chosen, if the Three were sent to jail, to step into their shoes and to attack the site again, so as to prevent the completion of the Bombing School.

A witness for the Air Ministry had assessed the cost of the damage caused to its property by the fire (including the destruction of a number of wooden buildings) at £2355 (equivalent to around £120,000 today) plus further damage worth £300 (£15,000) to equipment personally owned by the workers. The DPP decided, therefore, that it was appropriate to charge the Three with an additional, more serious offence of setting on fire buildings belonging to the Crown, contrary to section 5 of the 1861 Act. After hearing the evidence of the prosecution (which was not challenged by the defendants) the Pwllheli justices, when the case came before them again on the 16th of September, decided to commit the Three, on bail, to stand trial at Caernarfon Assizes, which were due to commence on 13th October. Getting the case before a jury was exactly what the Party wanted, of course.

Preparing for the Assizes

Looking forward to the Assizes, the Assistant DPP, Arthur Sefton Cohen, wrote to Chief Constable Williams on the 28th of September to request specific information. Mr Sefton Cohen had clearly taken seriously the Chief Constable’s warnings that the offence was part of a campaign of purposeful law-breaking on the part of the Party and realised that its members or supporters might be chosen to be members of the jury that would decide the case. He questioned whether the Chief Constable had reason to believe the trial would not be fair. He added: “I should also like to know if it is possible for you to obtain a copy of the jury panel before the trial and to let me have it together with your observations upon anyone on the panel so that I may instruct counsel as to whether a challenge should be made to any particular juror.”

It was the custom, at that time, for the High Sheriff to publish, before each Assizes, a list of prospective jurors – the “panel” – from which the jurors for each case would be selected. Police would check the panel names to see if someone who was disqualified from serving had been included on it by accident or if there was anyone on it who had personal links with a defendant or witness. Interfering with jury composition on the basis of jurors’ political charges could be something much more controversial, of course, if it came to light. But the Chief Constable had portrayed the Party as some sort of extremist cell – nothing more than a “noisy clique”. His general advice to the DPP was, therefore: “There is strong feeling of sympathy for the defendants amongst the Party, comprising mainly of students, school teachers, Non-conformist ministers and a fair number of quarrymen. It is difficult to express an opinion as to whether the trial is likely to be a fair one. As far as I have been able to scrutinise the panel of jury, apart from my remarks thereon, I am of the opinion that the jury will be guided by the evidence.”

What then were the comments he made on individual prospective jurors? 56 prospective jurors were summoned to come to the Assizes but three of them were excused due to illness and so on. Of the remaining 53, the Chief Constable advised that four were “sympathiser(s) of the Party” and another was “An active leader in the Welsh Nationalist Party”. That was a reference to the first name on the list, one Willam Ambrose Bebb. As everyone knew that Ambrose Bebb was one of the most prominent members of the Party and had worked closely with Lewis Valentine no one would have been surprised to see him excluded from the jury that was to hear the case. But in the event, he was not chosen and neither were any of the other four whom the Chief Constable believed to be Party supporters. The prosecution did not have to decide, therefore, whether they should exclude jurors on the basis of their perceived political opinions.

Caernarfon Assizes

The Judge who was to visit Caernarfon in October 1936 was the Hon. Sir Wilfred Hubert Poyer Lewis, who was born in London but of Welsh descent. His grandfather was a Pembrokeshire priest who was promoted to be Bishop of Llandaff and although Mr Justice Lewis was educated at Eton and Oxford he had started his career as a barrister in Cardiff and served in a Welsh regiment during the Great War. He did not speak a word of Welsh, of course, and it was the first time, since being appointed a judge the year before, that he had administered justice in North Wales.

The legal position at the time was that the court had to be held in English, including the official recording of the evidence. But the judge had a discretion to permit a witness or party to speak Welsh if justice demanded it, with ad hoc arrangements being made to interpret from Welsh to English. By the 30s, a growing trend had been noted on the part of some Judges, particularly those not accustomed to sitting in Wales, to refuse to allow the use of Welsh by those who appeared to be able to speak English. No one knew what Mr Justice Lewis’s attitude would be when, as everyone expected, the Three claimed to defend themselves in Welsh.

The defence’s strategy was that the burden of presenting the Three’s case would fall largely on the shoulders of Saunders Lewis and Lewis Valentine. It was decided that they would represent themselves, while D. J. Williams would be represented by a 30-year-old barrister, a native of Mountain Ash, Herbert Edmund Davies (afterwards Lord Edmund-Davies).

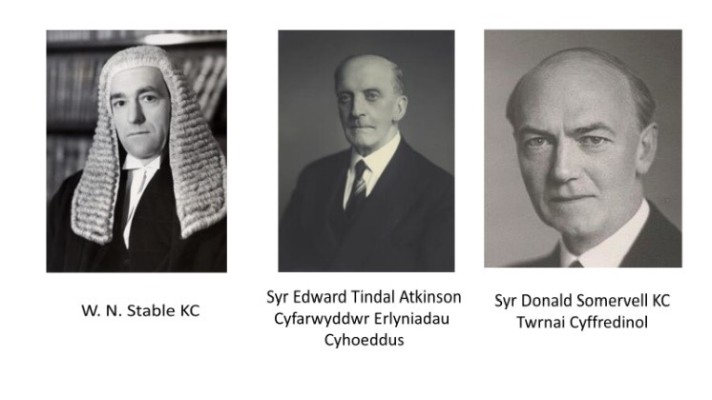

Edmund Davies’ role in the case was very limited but the Party felt it would be advisable to have someone on hand to keep an eye on legal and procedural questions – a wise decision as Edmund Davies had to remind the judge of the defendants’ rights to challenge jurors. E. V. Stanley Jones, was there, of course, and another solicitor was also employed, to assist with the defence, Mr H. Cornish of the firm of Thompson’s of London. The Three’s legal representation was paid for out of a special public fund collected for the purpose. The prosecution was led by W. N. Stable KC, one of the stalwarts of the North Wales and Chester Circuit, who divided his time between London and Plas Llwyn Owen, Llanbrynmair.

In the same way that the prosecution had scanned the list of prospective jurors to see who was likely to favour the defence, the defendants and their advisers had been considering challenging the jurors who they thought would be least likely to sympathise with their case. They chose to do so largely on the basis of the linguistic background of the prospective jurors. Five non-Welsh prospective jurors were removed, and a further five were chosen to replace them, all of whom were Welsh-speaking. The Judge referred to this process, the exercise by the defendants of an undoubted right they had under the law, as a “farce”, making that criticism of the defendant’s conduct in the presence of the jurors, of course.

The evidence

The Three did not dispute any part of the prosecution’s evidence other than the story of the night watchman, David William Davies, that two men (whom he had been unable to identify) had assaulted him during the raid on Penyberth. The Three denied there was any truth in this and asserted that there was no sign of Mr Davies on the premises when they were there. Although no charge of assaulting Mr Davies had been formally made against the Three, and the evidence on the point was therefore technically irrelevant, it was unavoidable that they should spend time denying Mr Davies’s account, for fear that the jury would believe that the Three had been violent towards him.

Although Mr Justice Lewis had been reluctant, at first, to let the Three speak Welsh because he was confident they were fluent in English, he had, by the end of the prosecution’s evidence, had an opportunity to reconsider. He allowed the Three, in presenting their defence, to do so in Welsh, with their words translated, sentence by sentence, by Mr Gwilym T. Jones, a trainee solicitor from Pwllheli (who subsequently became Clerk of Caernarfonshire County Council and a leading member of the Gorsedd). But while the Judge eventually adopted a more conciliatory attitude towards the use of Welsh, it was his initial hostility, it seems, that has remained in the public memory.

The Three, when questioned, admitted that they had lit the fire at Penyberth. At the conclusion of both sides’ testimony, there was, therefore, no doubt that the Three had set the site on fire. They did not claim to have any legal authority to do so. What, then, was their defence?

Addressing the Jury

On behalf of D. J. Williams, Edmund Davies limited himself to reminding the jury that, ultimately, they had the right to decide whether the Three were guilty or not. Lewis Valentine made an address laying out the pacifist argument against the Bombing School. He tried to convince the jury that the plan was contrary to the moral law since aerial bombardment was an extremely inhumane method of warfare. He argued that the practice should be banned by international treaty rather than promoted. He asked the jury to place the moral law above English law. Saunders Lewis’s argument was based largely on nationalist considerations, emphasising the Government’s unwillingness to listen to Wales’ opposition, as a nation, to a project that would harm Welshness and endanger peace. He endorsed Lewis Valentine’s call on the jury to acquit them, placing national and Christian principles above law. The Judge repeatedly interrupted Lewis Valentine’s and Saunders Lewis’s addresses, claiming that their arguments were irrelevant and that only “English law” counted. He made the same point in his instructions to the jury. The only question the jury should consider, according to Mr Justice Lewis, was whether they were certain that the Three had set fire to the site, contrary to English law.

The prosecution clearly did not anticipate any difficulty in obtaining a verdict of guilty from the jury. The Chief Constable had advised that the Party’s supporters were a very small group and none of those whom he believed to be their sympathisers had been selected to be on the jury. Prosecuting counsel W. N. Stable had been asking around Wales about attitudes towards the Three and his finding, which he shared with DPP officials, was that “Public Opinion is dead against the men, it seems, except for a very small minority.”

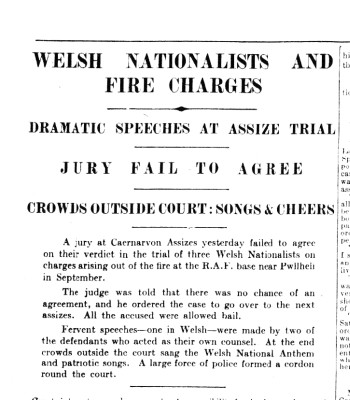

Jury fails to agree

But after considering their verdict for only three-quarters of an hour, the jurors returned to court and reported to the Judge that they were unable to agree on a verdict, with the divide so deep that it would be futile to spend more time discussing. As it was not possible, in those days, for a jury to reach a verdict on any basis other than unanimity, Mr Justice Lewis had to adjourn the case until the next Assizes in the new year, and he released the Three, once again, on bail.

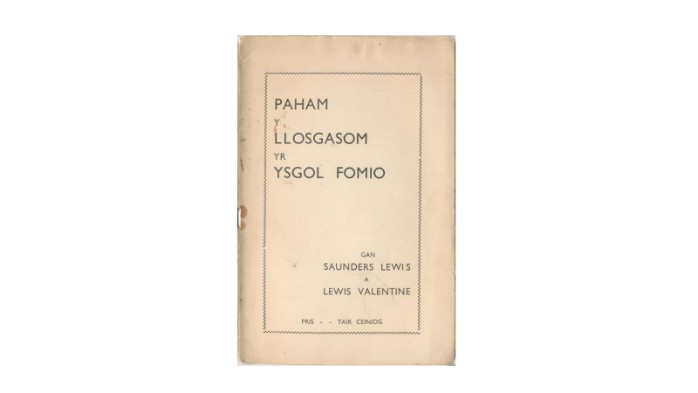

The crowd outside the court had already been singing Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau, disrupting, at times, proceedings inside but, as it became known that the jury had been unable to agree, the singing broke out even more strongly. Already, copies of Saunders Lewis and Lewis Valentine’s speeches to the jury, in the form of the pamphlet “Paham y Llosgasom yr Ysgol Fomio” (“Why We Burned the Bombing School”) were on sale on the streets of Caernarfon for 3 pence each.

Shocking news

The jury’s unwillingness to find the Three guilty was seen as a major victory for their case. The Party envisaged that the same outcome would be repeated when the case came before the next Assizes and that the prosecution would ultimately have no option but to drop the charges against the Three. The Plaid began organising public meetings across Wales to support them. But at a meeting of the Party’s Executive Committee on the 31st of October there was a startling report from J. E. Jones, “(W)e have received information, from someone claiming to be close to its source, to the effect that the Crown is closely watching the situation in Wales in order to determine whether it would make a request for the case to be moved to London, and that we should keep as silent as mice lest we cause this to happen. This puts us in a pickle. We would not, by giving the country an opportunity to show its enthusiasm for the three, to want to cause the case to go to London and for all three to go to jail. On the other hand, it was necessary to rise up strongly against the Bombing School.”

The implications of transferring the case to London, a move which, with the consent of the High Court, was allowed under the Central Criminal Court Act 1856, were inescapable, The strategy of making the case the centrepiece of the campaign in Wales against the Bombing School would be seriously undermined and there would be no chance of a jury in London refusing to convict the Three.

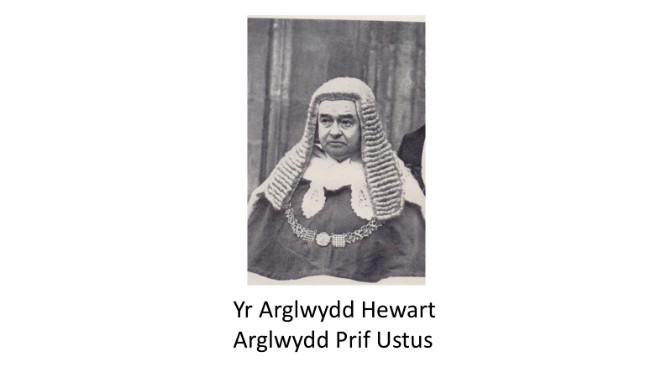

The question of applying to the High Court to move the case to London was discussed on the 12th of November, with the Attorney General, Sir Donald Somervell KC, the Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Edward Tindal Atkinson and the prosecution’s counsel, W. N. Stable KC, all present. It was decided to proceed with an application and there were hearings before the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Hewart, Mr Justice Swift and Mr Justice McNaghten at the High Court in London on Monday November 23rd and Monday 7th December.

The prosecution was represented by the Attorney General himself and such was the importance of resisting the move, in the Party’s view, that it enlisted the service of one of the most prominent (and costly) barristers of the day, Norman Birkett KC, to try to do so.

Norman Birkett KC

But he did not succeed. There was no doubt that the Three had set fire to Penyberth deliberately and without legal authority. The defendants had confessed and even taken pride in the deed. They had urged the jurors to decide the case on grounds other than principles of law. The proceedings took place in an emotional atmosphere, with the crowd outside singing Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau so loudly that it was difficult, at times, to hear what was being said inside the court. The addresses of two of the Three had been published and were on sale immediately after the conclusion of the hearing. And supporters of the Three had been urging any who might be chosen, next time, to be jurors to follow the example of the original jury and refuse to find them guilty. There was, therefore, sufficient evidence to support the prosecution’s argument that, if the case were to be heard again in Caernarfon, the jury would be placed under exceptional pressure which could influence their decision. As the High Court recognised no constitutional principle that Welsh people should stand trial in front of a jury of their fellow countrymen, it was inevitable that the Court would agree that the objectives of justice (the relevant legal test) justified moving the case to the Central Criminal Court, as the 1856 Act allowed.

Wales’ reaction to the decision to move the case to London

By the time the application was finally decided by the High Court it had already drawn a hornet’s nest on the head of the Government. The newspapers received piles of letters accusing the Government of undermining the rights of the Welsh by depriving the Three of their right to lay their case before a jury of their fellow countrymen, in their own country and in their own language.

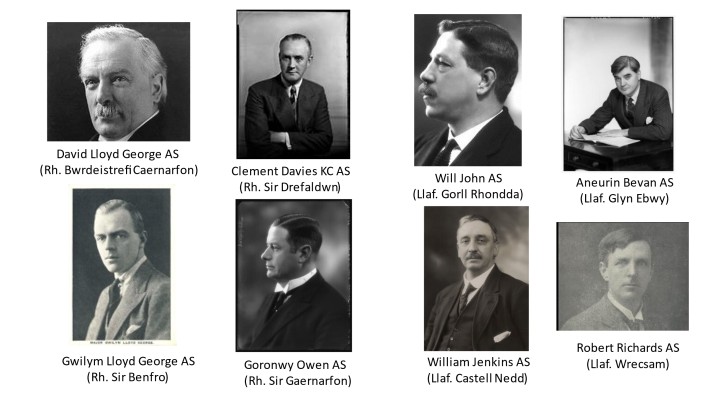

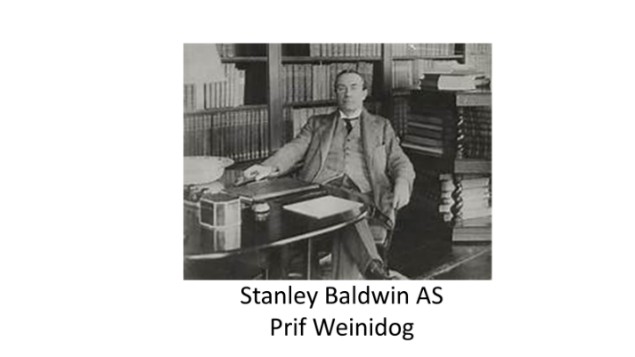

Criticism of the decision to move the case was not limited to those who had supported the Three’s opposition to the Bombing School. Local MPs David Lloyd George and Goronwy Owen had kept their heads down quite successfully during the campaign, with Lloyd George, as the Prime Minister responsible for setting up the RAF, reluctant to condemn the principle of improving its efficiency. But his reaction to the decision to move the case to England was scathing: “I think this is a piece of unutterable insolence, but very characteristic of the Government. They crumple when tackled by Mussolini and Hitler, but they take it out on the smallest country in the realm…. This is the First Government that has tried Wales at the Old Bailey.” A wave of protest against the intention arose from Welsh MPs from all parties, and the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, had to receive a delegation that included prominent figures such as Goronwy Owen, Gwilym Lloyd George and Clement Davies from the Liberals and Robert Richards, Wil John, William Jenkins and Aneurin Bevan of the Labour Party. (Lloyd George himself was on his way to the Carribean but sent a message supporting the opposition.)

In response to a Parliamentary question by Robert Richards, Labour Member of Parliament for Wrexham, the Attorney General tried to distance himself and the Government from the decision. “Facts were brought to my notice which, in my view, made it my duty to apply to the Court for the transfer to the Central Criminal Court on the grounds that such transfer, in the wording of the Act of Parliament, was “in the interests of justice””.

The Old Bailey

As it would be futile to try to convince the Old Bailey jurors of the correctness of the arguments presented at Caernarfon, the Three did not bother to make any addresses to the jury at the conclusion of their evidence there and were found guilty by the jury without them even leaving the court to discuss the matter. Another wave of protest ensued, with Professor W. J. Gruffydd, who had by now become one of the Party’s vice-presidents, declaring in the Western Mail that the Government had struck a fatal blow to the idea of impartial English justice and, thereby, destroyed “the only decency left in the English in the eyes of modern Welshmen.”

As it would be futile to try to convince the Old Bailey jurors of the correctness of the arguments presented at Caernarfon, the Three did not bother to make any addresses to the jury at the conclusion of their evidence there and were found guilty by the jury without them even leaving the court to discuss the matter. Another wave of protest ensued, with Professor W. J. Gruffydd, who had by now become one of the Party’s vice-presidents, declaring in the Western Mail that the Government had struck a fatal blow to the idea of impartial English justice and, thereby, destroyed “the only decency left in the English in the eyes of modern Welshmen.”

What was behind the decision to move the case to London

Despite the Government’s argument that moving the case to London had been inevitable in the interests of justice, the version of the decision that has been accepted by the national movement and by many others in Wales, is that it was a politically oppressive move. It was believed to have been taken by the Government in London in order to punish the people of Wales for being so presumptious as to challenge the authority of the state. But is that entirely true? Or is there another interpretation which is more complex and perhaps less comfortable for us Welsh.

On 25th October 1936, twelve days after the first trial in Caernarfon, Chief Constable Edward Williams wrote to the DPP with his comments on what had happened. Bearing in mind his goal of using the case to restrain the Party, and his view that it was nothing but a noisy clique, what had happened was a disaster, and the last thing he wanted to see was the same thing happening again. To demonstrate to the DPP that very decisive steps had to be taken to avoid this, he attached a copy of the panel of prospective jurors which he had marked to show which jurors had been prepared to find the Three guilty and which were not – 7 for guilty and 5 against (none of the five, by the way, had been on the police list of Party supporters).

This clearly showed how divided the jury had been. It had not been a case of one or two stubborn individuals. The origin of his knowledge of jury deliberations was what he described as “discreet enquiries” among them. Although such enquiries were not illegal at that time, the public reaction to the police’s interest in jury proceedings would probably not have been favourable, particularly bearing in mind the political implications of the case, which explains why the enquiries had to be “discreet”. It is worth noting that one of those named as refusing to find the Three guilty was the jury foreman, John Harlech Jones of Criccieth. His attitude had hardly been a secret as he had been winking at Lewis Valentine during the hearing and had sought him out that evening in order to assure him that he had been one of his supporters.

As well as referring to the deep division in the jury, the Chief Constable, in his analysis, emphasised the atmosphere outside and inside the court during the trial. A crowd had gathered in support of the Three who, according to the Chief Constable, included “Students from Bangor University, female School Teachers (and) unemployed quarrymen from outside Caernarvon” – all of whom, he believed, were supporters of the Welsh Nationalist Party. The outcome of the case had given “a great stimulus to the Party and it is said by them that a similar result will happen again if the defendants appear before a Welsh jury”. The jury’s failure to reach a decision was, he believed, “(a) challenge to the Law of England”. He finished by expressing the view that “that a fair trial cannot be obtained here and that the trial should take place if possible at the Old Bailey”.

Responsibility for moving the case

We see, therefore, that it was not the prosecutor, nor the Director of Public Prosecutions nor the Attorney General who made the original suggestion that the case be moved from Caernarfon to London but the Chief Constable of Caernarfonshire, Edward Williams. The move of the case out of Wales and to London was necessary, according to him, to secure a “fair trial”, a concept which, in the Chief Constable’s view, meant one that hindered the development of the Nationalist Party.

And, having regard to the response of the DPP and the Attorney General to his suggestion, it is clear that the Government did not share the Chief Constable’s view that a fair trial would not be possible before any Welsh jury. Such was the strength of the objection raised against the application to move the case to London that the Attorney General looked for another option, admitting that he had not anticipated that the idea of moving a case from Wales to England could be so controversial. At the end of the final hearing in front of the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Donald Somervell rose to make it clear that the prosecution would be satisfied if the case was moved not to the Old Bailey but rather to somewhere in Wales other than Caernarfon. He suggested Cardiff as a possibility. But by then it was too late. As Lord Hewart pointed out, the only application before the Court was for the case to be moved to London. As the evidence showed that, in his view, the interests of justice would be better served in London than in Caernarfon he did not feel he needed to consider any alternative.

It is clear, therefore, that the impetus for moving the Penyberth case from Caernarfon to London originated not in Westminster but in the office of Edward Williams, Chief Constable of Caernarfonshire. One must ask how someone whose salary was paid by the people of Caernarfonshire could be so willing to deprive them of the right to administer justice in their own county? The answer, I think, is that he saw his function as Chief Constable not, primarily, in terms of protecting the people of the county and their rights but as custodian of “English law” and the British order in general. Ironically, his zeal for that order had the effect of transforming the Penyberth case from being a matter of primarily local interest to one that heightened patriotic sentiment from Anglesey to Monmouthshire.

Although there has been considerable change in the organisation of the courts since 1936, and in their attitude towards the use of Welsh, the Welsh courts are still nothing more than a region of those of England. By the next general election for Westminster five years will have passed since the publication of Lord Thomas of Cwmgïedd’s report on “Justice in Wales for the People of Wales”. That called for authority over the Welsh courts to be transferred to the Cardiff Bay Parliament. Only achieving that will be able to draw a final line under the disrespect towards the residents of Wales highlighted by the Penyberth case.

© Keith Bush, August 2023