During the annual conference in Llandudno in September 2011, the Plaid Cymru History Society organised a meeting to commemorate the life of JE Jones, who served as party General Secretary between 1930 and 1962. This is the address by the Chair of the society and one of his successors in the post, Dafydd Williams.

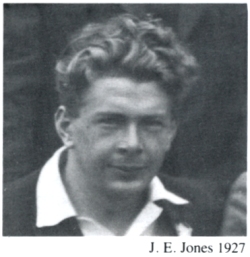

One of the earliest photographs from Plaid Cymru’s archives shows a group of people gathered at the 1927 Summer School at Llangollen. At the end of the front row is a young man with curly hair, his face full of energy and enthusiasm. Naturally I never knew the strong, young JE Jones who delighted in day-long expeditions across the mountains of Wales. By the time I met him in the mid 1960s, his robust good health had left him – a consequence, some said, of his incessant overwork for the cause of Wales. But his spirit and dedication to his country were as strong as ever.

John Edward Jones was born in December 1905. That meant he was ten years or so younger than Saunders Lewis and Lewis Valentine, and unlike them part of the generation that escaped the horrors of the First World War. His childhood home lay near the village of Melin-y-Wig, a hilly district about seven miles from Corwen and ten from Ruthin, the stamping ground of Owain Glyndŵr.

From the high ground behind the family farm, Hafoty Fawr, a clear day would give you a 360-degree view of the mountainous heartland of Gwynedd, Clwyd and Powys, which he describes in a lyrical passage in his important book Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid – half autobiography, half history of Plaid’s first forty years. It would be fair to describe JE as a patriot from his earliest days, drawing inspiration from the mountains of his birthplace: in fact he describes himself as ‘Mab y Mynydd’, the son of the mountain.

Before he had reached his first birthday, JE’s father died; but somehow his mother kept the family farm going with the help of her family, JE’s two brothers in particular, both of whom left school at 14 years of age. JE himself was to tread a very different path, despite his deep attachment the rhythm of agricultural life and the rural culture of Melin-y-Wig, with all its concerts and eisteddfodau. He won his way to Bala Boys Grammar School, Ysgol Tŷ Tomen, staying in Bala during the week. For all that Bala was a solidly Welsh-speaking area, everything in the school was in English. Was it this that fired up his lifelong support for Wales and the Welsh language? He tells the story of how he and a friend intervened to prevent a teacher picking on one of their fellow pupils who spoke little English – and succeeded in putting a stop to it. Then during the summer holidays in August 1923, after delivering eggs and butter to the village shop, he read a newspaper account of the meeting in Mold of a new movement with the odd title of ‘The Three Gs’, an acronym for y Gymdeithas Genedlaethol Gymreig, the Welsh National Society. This was one of the three groups that later came together to form Plaid Cymru; and a year or so later JE was to join it, as a first year university student at Bangor, where he studied Welsh, English and Mathematics, which he described as a “somewhat unusual combination”.[1]

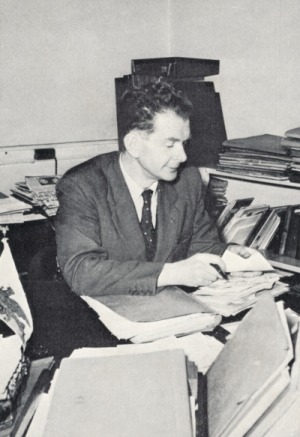

JE Jones – Architect of Plaid Cymru in his office in Caernarfon

Soon after, he heard reports of the launch of Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru in Pwllheli, and in October 1926 he attended a Plaid meeting in Caernarfon, filling in a membership form there and then. The forms were collected by HR Jones, a thin young man with a pale complexion: little did JE know that in a few years’ time he would be taking his place as Plaid Cymru’s general secretary. Within a month, a Plaid branch had been set up in the college in Bangor, with JE as secretary; by the summer it had nearly 80 members. JE stood as the party’s candidate in a mock election in November 1927 – and after a barnstorming campaign, he won! Could this have been Plaid’s first ever election victory? “I learnt then,” he was to say, “that it was easier to win over intelligent English people than a number of servile Welsh individuals.”[ii]

Once his University days were over, it was time to look for work. With a depression already looming, he applied for a teaching post in east London – and got it, one of four appointments out of 60 candidates. It seems most of the interview was spent discussing self-government for Wales! In no time at all, he had become secretary of Plaid Cymru’s London branch, although he also found time to play football for London Welsh Second XI and tennis during the summer.

Then came a decisive turning point in the young teacher’s life. After a long illness, HR Jones, the main driving force behind the foundation of Plaid Cymru, died. Despite fears about being able to afford it, the party leaders decided that a full-time successor had to be appointed. JE, together with a friend, the Guardian journalist

Gwilym Williams, decided they would both apply – using exactly the same wording, and giving each other’s name as a reference! JE was appointed – to a post he loved: “I was Secretary and Organiser of the movement for Welsh freedom from December 1930 until May 1962, when the old heart said it could take no more.”[iii]

It is interesting to compare the two Jones, HR a JE. One footnote, perhaps trivial but worth noting, is this: both of them succeeded in restoring the traditional names of their home communities; from Nasareth to Deiniolen in the case of HR, Cynfal to Melin-y-Wig in the case of JE. There was certainly a strong similarity in one aspect of their characters – an unswerving devotion to the cause of Wales and the Welsh language, and a vision of their country as taking its place among the world’s fully fledged nations. To which we can add the readiness to work without stop. I am grateful to Dewi Rhys, JE’s son, for these recollections of his father (my translation): “He was never idle. He would be on his feet about 5 every morning – either on the little typewriter, or in the greenhouse where he would ‘relax’ by transplanting hundreds of small plants, with the garden a sea of colour every summer. He was delighted to hear people making complimentary comments about the garden as they passed by. Even on holiday, he wasn’t idle. He would write diaries and bind them together as book after we came home.”[iv] Such commentaries were to form the basis for Tro i’r Swistir, the book he later wrote about their visits to Switzerland.

But the differences between the two are also revealing. As ever, JE is full of praise for his predecessor but he could not but observe the fact that party branches and rhanbarth organisations had languished and ceased to exist during HR’s illness: “To all intents, I was obliged to rebuild Plaid Cymru all over again.”[v] Plaid’s principal historian, D Hywel Davies, goes further, describing HR in these terms: “a restless visionary, longing for vigorous action on behalf of Wales rather than a desk role”. By contrast, JE “though prepared for radical action, was blessed with a painstaking nature more fitted to the task of careful organisational planning”.[vi] Hywel Davies also points to JE’s background as a University graduate and qualified teacher, concluding that this made him more comfortable among the membership Plaid was attracting.

JE took up his post on 1 December 1930, working from a small office in Caernarfon adjacent to the Pendref hotel where he took lodgings. What followed was a 32-year ‘stretch’ in which he became the lynch pin of party activity. JE soon established himself as the centre of communication and information for the party; and Plaid Cymru became noted for the quality and quantity of its publications. In the first four years of existence, it had published just one substantial pamphlet, Saunders Lewis’ Principles of Nationalism. Once JE took up the reins of office, Plaid began producing a steady stream of literature. It is worth noting that this output included several solid works on economic policy – including The Economics of Welsh Self-Government by Dr DJ Davies (July 1931) and two by Saunders Lewis – The Case for a Welsh National Development Council (1933) and Local Authorities and Welsh Industry (1934). These publications, supplemented Y Ddraig Goch, which slightly preceded the foundation of Plaid Cymru, and its English-language counterpart, Welsh Nationalist, set up in 1932.

The emphasis was very much on selling and sales campaigns rather than giving away; although JE developed the habit of what he called ‘meithrin tawel’ (quiet cultivation), sending the latest publication with a friendly covering letter to a selected range of prominent people – the artist Augustus John was one he said joined the party as a result.[vii] I recall (to my shame) Gwynfor Evans pointing frequently to the relative dearth of Plaid publications during the 1970s and 1980s by comparison with JE’s term of office.

Then there is PR. While persuading others to produce detailed publications, JE himself was master of collecting the telling quote and the killer fact, which he described as ‘bwledi’ – bullets. This led on naturally to press communications, in which he proved expert – both in crafting press statements and cultivating journalists. I like his restrained critique of some of his fellow Nationalists in this area: “I found one of the most difficult things, in the early years, was to educate our local officials – secretaries or correspondents – to write ‘effective pieces’ for the Press and to develop friendly relations with journalists. But that came, over time.”[viii] JE could have taught 21st century spin doctors a trick or two: his advice on using the Press remains as true today as ever, for all the changes brought by the age of the internet, Facebook and Twitter.

One early priority was building the party, from the tiny handful he inherited in 1930. This proved painfully slow, although JE set about the task in his typically systematic way, moving from county to county, badgering members to establish county committees and in due course branches. Saunders Lewis was characteristically acerbic about the rate of progress: at the end of 1935, after praising JE’s work, he asked: “But where are his disciples? An organiser of the same calibre in every Rhanbarth Committee would transform the course of Plaid Cymru.”[ix]

Here it’s worth recalling some home truths. Plaid Cymru was still small. It was also (in terms of the age of its members) overwhelmingly young. Because it was small and young it was also poor, very poor. This partly explains how few elections it fought – one Parliamentary seat in 1929, two in 1931 (Caernarfon county and the University of Wales), back down to one in 1935. By the way, 1935 was the first election for Plaid to use canvassing – a technique JE adapted from his contacts with parties in Denmark, Ireland and England. Local elections contested were also few and far between. Perhaps poverty isn’t the whole truth – the indefatigable DJ Williams complained bitterly at the lack of fighting spirit, describing Carmarthenshire county committee as “a dead body”.[x] This was 1935!

One technique JE pioneered to tackle Plaid’s financial problems was the St David’s Day Fund, based on the experiences of Fianna Fáil. The first appeal, in 1934, raised the princely sum of £250! Building party membership and funding went hand in hand with fighting campaigns – on a whole range of topics. Just one example – shortly after taking up his post JE launched a campaign to popularise use of the Welsh flag in place of the ubiquitous Union Jack. The first target was Caernarfon castle, whose Constable was none other than David Lloyd George. His opening gambit was typically modest, scarcely capable of rejection – simply equal status for the two flags on St David’s Day. A letter forwarded by Lloyd George to the Minister in London elicited a contemptuously negative response – just what JE was after of course. He promptly published it!

On St David’s Day 1932, clad top to toe in motor cycle gear, JE paid his sixpence and made his way to the top of the Eagle Tower, joined by three other conspirators, including Lloyd George’s nephew, WRP George. There they lowered the Union Jack, raised the Ddraig Goch and then stapled the ropes to the flagpole – JE’s planning of course included a hammer and staples in his rucksack. The spectacle of a large red dragon flag on the tower prompted cheers and a quick rendition of Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau from a crowd below; although the local constabulary soon appeared, and before long the Union Jack was back in its place. Later in the day, however, and quite independently, a group of Plaid students from Bangor showed up on the back of a lorry. They too got up to the Eagle Tower and succeeded in smuggling out the offending Union Jack, which met an unfortunate fate on the Maes.

The following St David’s Day saw a government U-turn. A large Draig Goch was raised as high as the Union Jack, and the ceremony was performed by none other than David Lloyd-George. Soon afterwards, the Welsh flag would fly from all government buildings on 1 March; and JE saw to it that party branches pressed the local authorities to follow suit. He then arranged production of more flags, selling them at a tidy profit.

Other campaigns involved moves to raise the status of the Welsh language – for example, shaming the Post Office into accepting prepaid envelopes with Welsh place names – building up to the successful drive to ensure Welsh language programmes on the BBC. A common theme in all these endeavours – and many more – was careful planning and a holistic approach – never missing out on an opportunity for good PR. This care was evident than during the burning of the Penyberth bombing school in September 1936, an operation remarkable for its secrecy and meticulous attention to detail. This included a spy – the young Alaw Non Rees, who from her upstairs window in Llanbedrog kept tabs on how much timber had arrived on site.

JE was one of seven people who played a direct role in the operation – he walked part of the way back to Caernarfon along the railway to avoid detection. The following morning in his lodgings he received a letter from Saunders Lewis – apologising for not informing him about the burning! It was of course an alibi – the Plaid leaders could not afford to have their office closed down and their organiser behind bars at such a crucial moment. JE remained free to organise nationwide protests. Dewi Rhys recalls seeing the bundles of telegrams of support sent to the Penyberth Three – Saunders Lewis, Lewis Valentine and DJ Williams – telegrams that JE had organised: by law they had to be delivered, even during a High Court trail, helping to maximise the impression of public support.[xi] He also arranged what I believe must still rank as the biggest ever party rally – a crowd of 12,000 welcomed the Penyberth Three back to Caernarfon from Wormwood Scrubs.

Penyberth and the two High Court trials that followed proved a pre-War high water mark for Plaid Cymru. JE argues that much of the new support the party won was dissipated by opposition to the coronation of George VI, a decision taken during Saunders Lewis’ prison sentence and a rare spell of sick leave for himself. Opponents also saw Lewis’ conversion to Catholicism as a chance to smear Plaid with the taint of fascism. The outbreak of War posed a huge challenge – even a mortal threat to the party’s existence, as Saunders Lewis openly admitted at the time. Yet somehow Plaid Cymru carried on, and even grew in influence as the war went on. The party hit back at its detractors with vigour and confidence. It resisted conscription, JE facing six separate courts and tribunals over three years, and doing so with some style. And it fought tooth and nail to save 40,000 acres of land in the Epynt range from seizure as a Ministry of War firing range. So in April 1940, JE found himself walking the mountains again, visiting every farm endangered; but London had its way.

Planning post-War election strategy – the SNP’s first MP Dr Robert McIntyre joins Plaid leaders in 1945

From 1942 the tide was clearly turning in the party’s favour. A by-election for the University of Wales seat saw Saunders Lewis take 23 per cent of the vote: JE notes (with satisfaction) that he was described as ‘cunning’ for his role as the “assiduous, astute and untiring agent”.[xii] And he had another reason to be happy. In 1940 he had married Olwen Roberts, secretary of the Caernarfon rhanbarth, the ceremony performed by Lewis Valentine. Two children, Angharad and Dewi Rhys, were to follow.

By 1945, Plaid Cymru emerged stronger than ever. For the first time it could lay some claim to be an all-Wales party, fighting seven seats in the general election. In the summer it chose a new leader, the 33-year-old Gwynfor Evans, and he and JE were to form a cohesive team for the next decade and a half. In fact, says Hywel Davies, it is from 1945 rather than 1925 than Plaid can be regarded as a political party, albeit still a party in embryo.[xiii]

Once again it fought a Ministry of War land grab, this time in Trawsfynydd, Meirionnydd and this time successfully. Again JE provided organisational flair: the police and army were outwitted by a diversionary group while the main protest used back lanes to stage a two-day blockade. By 1950 Plaid Cymru was fully engaged in the Parliament for Wales campaign and JE organised a series of rallies which would be held annually for a quarter of a century. The 1953 rally was one of the biggest seen in Cardiff. Unusually he took the chair – but his real input was planning and implementation. The build-up included a relay of torch bearers running from the Owain Glyndŵr Parliament House in Machynlleth to Sophia Gardens: JE ensured the speeches and messages went on long enough for the ensuing procession to be seen by crowds leaving Cardiff Arms Park.[xiv] He was also involved in the defence of the Tryweryn valley although by now he had more assistance.

JE chairs the 1953 Parliament for Wales rally in Sophia Gardens, Cardiff

Of course JE Jones was not without his critics. Some felt that someone of his background could not relate to the industrial, non-Welsh-speaking communities of south-east and north-east Wales. I think his track record shows otherwise. Tros Gymru is full of references to the need to appeal to those who do not speak Welsh. JE supported the move of the party’s office from Caernarfon to Cardiff in 1946 – in fact he personally located premises in 8 Queen Street. Dewi Rhys recalls that the official opening took place on 1 March, the day of his birth, with his father trying to be in two places at the same time – as usual![xv] His work enabled Plaid Cymru to spread its wings in the south after the war. For his part JE always showed a great reluctance to criticise fellow Nationalists. Here is one rare example: after praising the leadership of Saunders Lewis, he allowed himself this one comment: “But he did develop a tendency towards a mistaken prejudice sometimes against certain types of people; for example, he could suggest, about someone quite as courageous as himself, that pacifism was cowardice.”[xvi] The ‘someone’, of course, has to be Gwynfor Evans.

Others felt he was too close to the party elite; especially at times of strain within the ranks, as for example during the Tryweryn campaign. By 1950, the now ex-president Saunders Lewis was privately critical of what he called JE’s ‘parchusrwydd’, respectability, which he contrasted unfavourably with the militant tactics of the Welsh Republicans.[xvii] But JE was by his nature a loyalist, committed to supporting Plaid Cymru and its chosen leadership through thick and thin, whatever that might demand. He had proved himself more than ready for radical action: his willingness during the war years to oppose conscription as a nationalist and face prison demonstrates that. The ‘respectability’ of which Saunders Lewis complained was that of Plaid Cymru rather than JE: it reflected the determination of Gwynfor Evans to put post-War Plaid on course to be a truly all-Wales party rather than a nationalist pressure group.

Looking back, what is striking is JE’s willingness and ability to continue at his post, for all the problems and pressure Plaid Cymru faced. Could the party have held together during the 1930s, the 40s and the 50s without JE at the helm? Perhaps, but I find it hard to imagine how. His tombstone in Melin-y-Wig bears the dedication ‘JE Jones, Pensaer Plaid Cymru’ – a fitting tribute to the architect of Wales’ national movement.

JE Jones (1905-1970) is buried in the cemetery opposite the chapel in Melin-y-Wig, Denbighshire. A plaque on the wall of the former village school he attended also commemorates his life.

[1] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid. (Gwasg John Penry, Abertawe, 1970), p.37.

[ii] Ibid, p.40

[iii] Ibid, p70

[iv] Ebost i’r awdur gan Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, Mis Medi 2011.

[v] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.97.

[vi] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party 1925-1945: A Call to Nationhood (University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1983), p.187.

[vii] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.88.

[viii] Ibid, p.95.

[ix] Ibid, p.113.

[x] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party, p.204.

[xi] Email to the author by Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, September 2011.

[xii] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.276.

[xiii] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party, p.268.

[xiv] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid. p 307.

[xv]Email to the author by Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, September 2011.

[xvi] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.155.

[xvii] Emyr Hywel (Editor), Annwyl D.J. Llythyrau D.J., Saunders, a Kate. (Y Lolfa, Talybont, Ceredigion, 2007), p.182.