Category: Publications

First Newsletter of History Society

The first issue of the History Society’s Newsletter has been published.

The first issue of the History Society’s Newsletter has been published.

You can read it here >> Newsletter

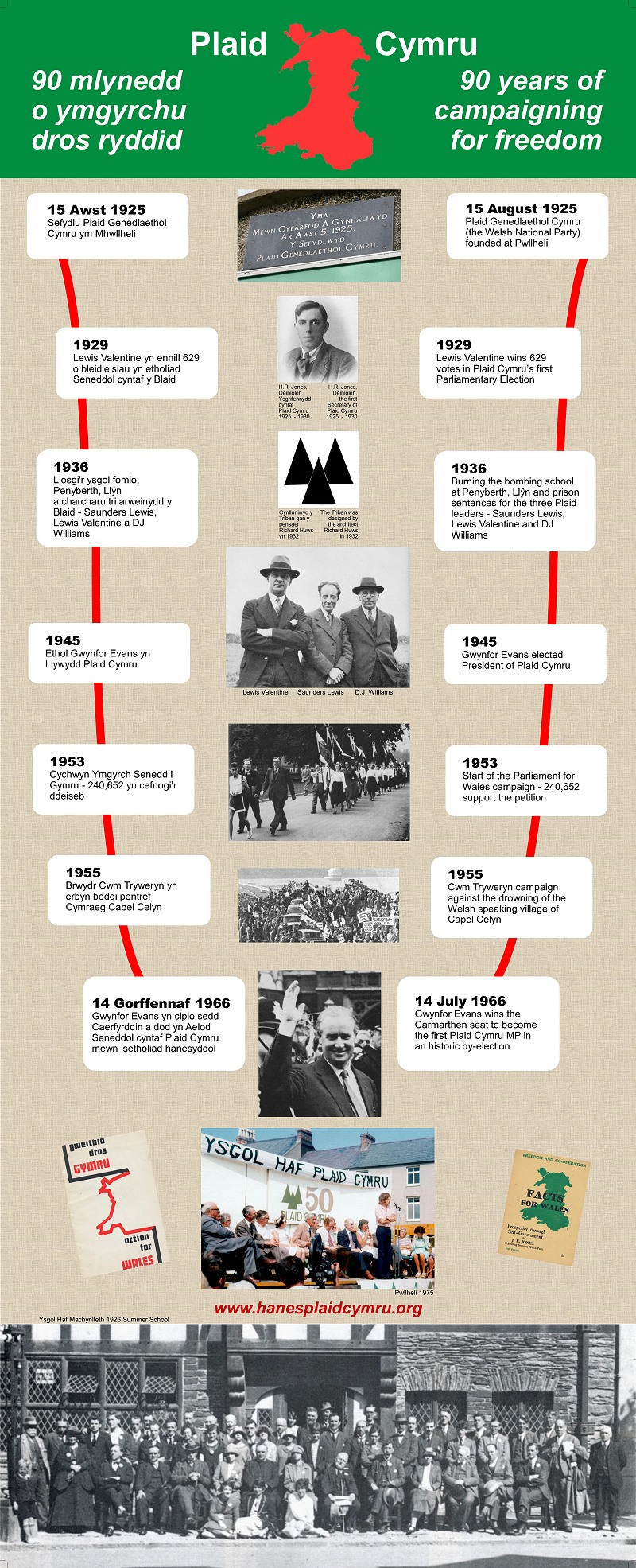

Magnus Maximus

Gwynfor Evans – Lecture by Peter Hughes Griffiths

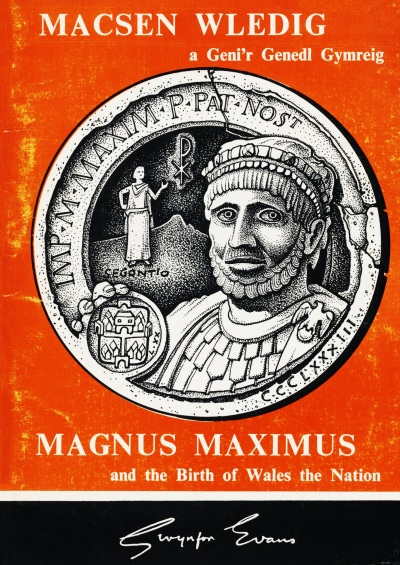

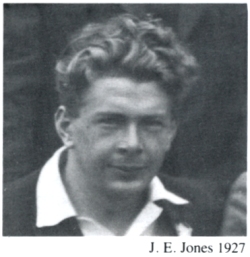

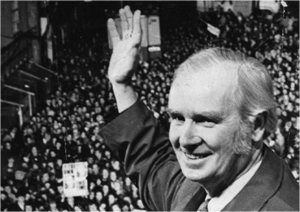

The first ever National Eisteddfod lecture to be organised by the Plaid Cymru History Society focused on the life of Gwynfor Evans and took place on 6 August 2012. It was delivered by Peter Hughes Griffiths, Plaid Cymru’s council group leader on Carmarthenshire County Council who served Gwynfor and Plaid Cymru as full-time organiser in the county. An extended version was given in Carmarthen on Friday 5 October as the Enid Jones memorial lecture. The Society is grateful to Peter for permission to reproduce the lecture on our website and to Councillor Alun Lenny for his kind help in supplying the photographs. This text has been translated from Welsh by Dafydd Williams.

GWYNFOR EVANS – THE LEADER AND THE MAN

Gwynfor Richard Evans was born on 1 September 1912 – one hundred years ago – in Y Goedwig, Somerset Road, Barry in the Vale of Glamorgan, the son of Dan and Catherine Evans and brother of Alcwyn and Ceridwen. After studying his life, reading extensively about him and getting to know him personally – the only conclusion we and future historians I am sure can draw is this: How could one human being achieve so much during his life – politically, yes – but also in so many other fields – and all of this for the sake of Wales. Gwynfor Evans was special, and a person completely dedicated to his country, as far as I know, uniquely in our nation’s recent history. There is that one estimate he travelled over a million and a quarter miles during his life – for the sake of Wales. And according to Graham Jones of the National Library – “Gwynfor’s collection is the biggest collection the Library possesses, and it is still far from complete.” In his biography of Gwynfor, the author Rhys Evans records that in 1989 he published his millionth word in his eleventh book. He went on to publish a number of books after that, all this quite apart from the hundreds and hundreds of articles he wrote in Welsh and English for the Plaid newspapers, Y Ddraig Goch and the Welsh Nation, as well as the endless weekly statements, leaflets and pamphlets – all of them in the age of the typewriter – where he acknowledges that his wife Rhiannon would do all the hard work for him. This was the era of the power of the printed word, a time when people read extensively, before the arrival of radio and television. Dr Pennar Davies said that his name is an integral part of the reawakening of Wales in the twentieth century, while to quote his biographer Rhys Evans once more – “It was Gwynfor who created the ‘national movement… Gwynfor was also the founder of the Parliament for Wales campaign … There is now a lasting memorial to that organisation in Cardiff Bay – It is the Assembly, the unmistakable symbol, for better or worse, of the desire of the people of Wale to live as a democratic nation.”

Gwynfor Richard Evans was born on 1 September 1912 – one hundred years ago – in Y Goedwig, Somerset Road, Barry in the Vale of Glamorgan, the son of Dan and Catherine Evans and brother of Alcwyn and Ceridwen. After studying his life, reading extensively about him and getting to know him personally – the only conclusion we and future historians I am sure can draw is this: How could one human being achieve so much during his life – politically, yes – but also in so many other fields – and all of this for the sake of Wales. Gwynfor Evans was special, and a person completely dedicated to his country, as far as I know, uniquely in our nation’s recent history. There is that one estimate he travelled over a million and a quarter miles during his life – for the sake of Wales. And according to Graham Jones of the National Library – “Gwynfor’s collection is the biggest collection the Library possesses, and it is still far from complete.” In his biography of Gwynfor, the author Rhys Evans records that in 1989 he published his millionth word in his eleventh book. He went on to publish a number of books after that, all this quite apart from the hundreds and hundreds of articles he wrote in Welsh and English for the Plaid newspapers, Y Ddraig Goch and the Welsh Nation, as well as the endless weekly statements, leaflets and pamphlets – all of them in the age of the typewriter – where he acknowledges that his wife Rhiannon would do all the hard work for him. This was the era of the power of the printed word, a time when people read extensively, before the arrival of radio and television. Dr Pennar Davies said that his name is an integral part of the reawakening of Wales in the twentieth century, while to quote his biographer Rhys Evans once more – “It was Gwynfor who created the ‘national movement… Gwynfor was also the founder of the Parliament for Wales campaign … There is now a lasting memorial to that organisation in Cardiff Bay – It is the Assembly, the unmistakable symbol, for better or worse, of the desire of the people of Wale to live as a democratic nation.”

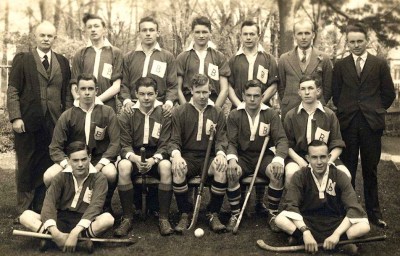

The opening sentence of the Welsh Academy’s Encyclopaedia of Wales describes him in this way: “The greatest patriot of 20th-century Wales, his dedication to his country did much to transform the national prospects of the Welsh people”. He received the Fellowship of a number of our colleges as well as serving as President of the Day in the National Eisteddfod more often than any other person in our time. Capel y Tabernacl in Barry was spiritual home for the entire family, with Gwynfor’s mother and father playing leading roles and his grandfather the Reverend Ben Evans its first minister. His father was a deacon and conductor of the mixed choir of over a hundred voices that performed the major oratorios on a regular basis. In the year 2,000 a new stained glass window was unveiled to honour the lives of Dan and Catherine, who set up well known, flourishing businesses in Barry town. Gwynfor attended Barry Grammar School where he captained the school’s cricket and hockey teams, and was selected to play in the Welsh Schools Cricket Team in 1930. Then it was off to University College, Aberystwyth and a law degree – and selection to play in the college cricket and hockey teams once more.

While in University, there took place two events that would have a strong influence on his later life – the first: “I would marvel at the dedication of the young men and women who sold Y Ddraig Goch on the streets of Aberystwyth – Gwenant Davies, Eic Davies and others.” And secondly – “but one day he saw a yellow coloured pamphlet outside a bookshop in Aberystwyth – The Economics of Welsh Self Government by DJ Davies. This booklet removed all kinds of doubt, and in the summer of 1934 he approached Cassie Davies in Barry and joined the national party.” At the time Cassie Davies was a member of staff at Barry College and in her book Hwb i’r Galon she recalls – “And this was the time that a remarkably good-looking young man from Barry, wearing an Aberystwyth college blazer, began to call to talk about this new party and ask to join it.” Gwynfor then went to Oxford University where he set up a party branch and became secretary of the famous Cymdeithas Dafydd ap Gwilym. He graduated there in 1936. Although he was to send an article from Oxford for his old school’s magazine, parts of which appeared in the Western Mail, it was in January 1937 that he published his first full article in Y Ddraig Goch, dealing with the establishment of the St Athan camp, and in the Plaid Cymru Summer School in Bala the same year he proposed a motion calling for official status for the Welsh language. And guess what – 400,000 signatures were collected in support of the proposal before the Second World War put paid to that effort. So you can see that Gwynfor had already made his first major strides in what was to be his life’s work – for the sake of Wales. He became a member of Plaid Cymru’s national executive in 1937 and within six years, in 1943, he was chosen as party vice-president. Then on 1 August 1945 in the Llangollen conference (five days before the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima) he was elected as President of Plaid Cymru at the age of just 32, the start of his great lifetime mission – he would remain president and leader for the next 36 years.

In the meantime he had married his lifelong partner Rhiannon and was living in Wernellyn, Llangadog where he launched a market garden venture. I like his description of how he fell for Rhiannon. In his autobiography Bywyd Cymro, available in English as For the Sake of Wales, Gwynfor describes how he called on Rhiannon’s parents in Cardiff – “I have to confess that my heart lost a beat the moment Rhiannon walked into the room. On seeing her again two months later amid the beauty of a summer’s day at Islaw’r Dref dressed in a very short light frock – beach wear no doubt – the boy from Barry fell head over heels in love!” They were married on St David’s Day 1941, and Pennar Davies says in his book that if heaven had ever arranged marriages this was surely one it had done well: “And the contribution of Rhiannon Evans to the work of her husband cannot be overestimated.” Gwynfor contested his first Parliamentary election in Meirionydd in 1945. He led the Llyn y Fan protest on New Year’s Day 1947 and that in Abergeirw in 1948 and was elected a member of the University Court’s Guild of Graduates and of the Welsh Independents the same year, as well as serving as Welsh Secretary of the Celtic League in the Colwyn Bay National Eisteddfod as early as 1947, when he was 34. It is evident that by the end of the 1940s Gwynfor Evans had established himself as a national leader with wide support among his people.

Gwynfor was elected to Carmarthenshire County Council in 1949 and was a County Councillor for 25 years. The 1956 County Council elections produced an interesting result, with 29 Independent councillors, 29 Labour and 2 Plaid Cymru. Plaid Cymru held the balance, and stranger still both Plaid councillors bore the name Gwynfor Evans – Gwynfor Evans of Betws, Ammanford and Gwynfor Evans, Llangadog. Gwynfor Evans, Betws took the county council to the High Court in London for failing to provide nomination papers in Welsh – and won his case, leading significantly to the establishment of the Hughes Parry Committee in 1963 to investigate the legal status of the Welsh language. In 1949 Gwynfor led Plaid Cymru’s most ambitious Rally ever – 4,000 people came to Machynlleth to call for a Parliament for Wales, and after Gwynfor’s speech one correspondent concluded that the accolade of Wales’ leading orator should be awarded to Gwynfor rather than Aneurin Bevan. There followed further Parliament for Wales rallies in Blaenau Ffestiniog in 1950 and then the great rally in Cardiff in 1953, with a quarter of a million people signing a petition presented to the House of Commons. Gwynfor fought Meirionydd in the 1950 General Election, the Aberdare by-election in 1954 and Meirionnydd again in 1955 and 1959. And what about the fight for Tryweryn? A rally in Bala in 1956 – “No sooner had Mr Gwynfor Evans got to his feet to speak than the thousands in the great marquee stood up to welcome him and give him prolonged applause.” And in his book Bywyd Cymro Gwynfor said– “And except for the Parliament for Wales campaign, Tryweryn was the most important of all our campaigns.” Gwynfor’s leadership during that battle have been recorded in detail and the deputations to Liverpool and so on are historical events. Gwynfor wrote – “The Welsh had been as united as ever any nation could be. Their opinion was completely ignored. The state of democracy in Wales was exposed.”

A young woman – Jennie Eirian Davies, married to a minister in Brynaman – stood as Plaid Cymru’s first candidate in Carmarthen in the General Election of 1955 and again in a by-election in 1957. Dewi Thomas writes about her in a book of tribute to her – “Her tireless dedication and brilliant talent in the fifties opened the door for Gwynfor’s success in the great victory in Carmarthen later on.” Indeed Jennie Eirian herself said after the 1957 election – “The Blaid will win this seat within 10 years.” That happened in 1966 – within 9 years! Where should I begin with Gwynfor’s victory in the 1966 by-election? That story deserves a lecture in its own right. You will get that in 2016 when we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the victory! All I wish to say tonight is that the fact that result took place changes the political history of Wales for ever. Gwasg y Dryw brought out a record of Gwynfor speaking after his victory, calling on his country to will a full life and the means of creating it, a Welsh government. Today that government exists. We are on the way to securing a comprehensive Welsh government, Gwynfor’s full vision. Think about him going to London and the House of Commons and entering the lion’s den – “As he showed me round the tea rooms, Emrys Hughes pointed to the Welsh table, saying, ‘I wouldn’t sit there if I were you ’– ‘Your name is mud there.’ Goronwy Roberts used to pass me in the corridor without looking at me. It may be difficult for some readers to recall how vicious George Thomas could be. He was extremely set in his anti-Welsh sentiment. He was the very scourge of Welsh nationalism and the Welsh language.”

That was the environment Gwynfor entered, but he took advantage of that imperial establishment to fight for Wales and call for self-government. Things like this – With the support of Plaid Cymru’s Research Group, he came to the conclusion that the best tactic was to wage a guerrilla war and ask numberless questions about the situation of Wales. Gwynfor’s question would drive the civil service crazy: by the end of the first year he had asked over 600 questions, all of them published together with their answers in three volumes –the Black Books of Carmarthen. Then the party set out Plaid Cymru’s case to the Royal Commission on the Commission in 1969. Losing Carmarthen in 1970 – after the Investiture, direct action by Cymdeithas yr Iaith and the FWA (if such a thing existed!). Then losing by just 3 votes in March 1974 and scoring a sweeping victory in October 1974. At half past three in the morning a crowd of 3,000 were on Nott Square to hear the result and that Gwynfor had taken 23,325 votes. This was the only seat that Labour lost anywhere in the United Kingdom that night. So back to London, but this time with the two Dafydds for company! His working day would often commence at nine o’clock in the morning and carry on into the early hours of the following morning. This was a crucial period for making the case for assemblies for Wales and Scotland – there were three nationalist MPs from Wales as well as seven from Scotland. The Government’s majority over the other parties was only three. Gwynfor said – “Here was the most hopeful political situation I had ever encountered”. The Government was compelled to yield to the pressure for parliaments for Wales and Scotland – and this marked the beginning of a long and difficult journey which has now taken place, much more so in Scotland than in Wales! The Labour Party took care to ensure that the devolution referendum in Wales and Scotland faced barriers so that it was impossible for the Yes vote to succeed. We remember Neil Kinnock and others in the Labour Party campaigning strongly against their party’s own policy and getting every facility to do so. The outcome was the Na vote in the 1979 Assembly referendum in Wales. Rhys Evans says – “Gwynfor experienced many highs and lows in his career, but this was the nadir. For him and his generation of nationalists, the referendum was more than a ballot on the administration of Wales; the referendum was a vote on the spiritual and existential question of whether Wales existed. He was devastated, not knowing which made him feel more sick … Welsh toadyism or Labour deceit and corruption.”

He lost the General Election that followed the Referendum because of publication of a BBC opinion poll days before the election that predicted that Gwynfor would come a poor third. In my personal opinion all this had been arranged by the ‘establishment’ to get rid of Gwynfor from the House of Commons. In fact, the BBC admitted following a detailed review of the company that carried out the opinion poll that were unacceptably far from the mark! Gwynfor’s response was – if he had won that election, with his health as it was at the time, he would no longer be in the land of the living! And then in 1981 after 36 years as President of Plaid Cymru Gwynfor stepped down from the helm in the Conference in Carmarthen. That is a quick sketch of the work and impact of Gwynfor in the field of politics. It was a very profound impact, and we would never be where we are today but for Gwynfor having accomplished so much. His political success is now acknowledged by everyone. A very very special man. But what is truly remarkable about this man is that he accomplished so much side by side with his political career. And what I want to do now is give you a taste of those accomplishments, and remind you of the other tremendous pioneering roles he played. And where should I begin?

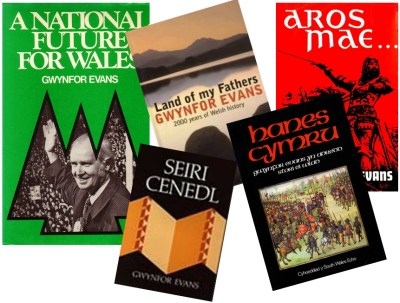

THE HISTORIAN

A few of Gwynfor’s many books

Gwynfor would almost invariably begin every speech with a history lesson. It didn’t matter where, or what was the occasion, the history of Wales was part of the message. He believed it was very important that we as a people should get to know our history. He campaigned to teach Welsh history in our schools – at a time when that was virtually non-existent, and he set about writing and publishing books, and encouraging others to do the same – “Gwynfor’s aim throughout his life was to awaken national consciousness through imbuing people with the history of Wales, restoring their memory and strengthening their desire to live.” (Dr Geraint Jenkins) He wrote history classics –Hanes Cymru/ History of Wales, through the South Wales Echo. Then Aros Mae, Seiri Cenedl y Cymry and Land of My Fathers. Picture him setting out on Christmas Day 1970 to write the first two pages of notes for Aros Mae! It was on sale within 7 months, with the first edition selling fast and a second edition soon in hand. Elin Garlick set about a translation into English, entitled Land of My Fathers. Three reprints were to follow and the publishers Tŷ John Penry commented– “this was the best seller of all the books we have published.” His other historical classic is Seiri Cenedl y Cymry, available in English as Welsh Nation Builders, portraits of the history of 65 men and women who contributed in different ways to the building and development of our nation. Think of all the research work needed to write historical studies and get the facts right! Gwynfor was a prolific author – of some 30 books in total – as well as pamphlets, leaflets and numerous books, in Welsh and English. He told me once of his intention to write one more book based on all his travelling around Wales – a study of Welsh chip shops as he had eaten in so many of them as he criss-crossed the country!

THE CHRISTIAN AND PACIFIST

We heard the Reverend Beti Wyn James and Mererid Hopwood assessing the significance of Gwynfor’s contribution in these two fields in the memorial service held in Capel y Priordy on Sunday 2 September. So I shall just summarise some of the main features. Gwynfor was a teacher in the young people’s Sunday School in his chapel, Providence Llangadog, for many years, and what is special id this – wherever he had been on the Saturday night – he would almost always return for his Sunday School class the following day. Read the full chapter about Gwynfor the Pacifist in the book by Pennar Davies – it gives us a comprehensive and detailed picture of the depth of his thinking and his faith.

Defending the land of Wales – successfully – Trawsfynnydd, 1951

He was brought up in a Christian family in Barry where his grandfather The Reverend Ben Evans was the first Minister of Capel y Tabernacl. His uncle Idris (his father’s brother) was also a minister and a first-class preacher. Gwynfor became Chairman of the Union of Welsh Independent Churches when he was just forty-two years of age. No-one as young as that had ever been elected before. And his son Guto was also President of the Union in recent times. It is important to recall that in his maiden speech in the House of Commons Gwynfor based his hopes for Wales on the Christian values of its heritage. He occupied a number of positions in the Independents’ organisation and he also played a key role in setting up Tŷ John Penry and its administration. His Christianity was always practical. “I am first a pacifist and then a nationalist” were Gwynfor’s words when given an unconditional discharge after appearing before a military Tribunal in Carmarthen in 1940. After writing his first article about St Athan in 1937 he came under the influence of his great hero George M LL Davies, becoming Secretary of Heddychwyr Cymru, the Welsh peace pledge movement and responsible for its tent in the Cardiff National Eisteddfod in 1938. Throughout his life he led protests and spoke in peace rallies – Swansea Rally in 1940, the great rally to defend Epynt where 400 people were turned out of their homes, the Abergeirw rally of 1948 and Trawsfynydd in 1951, with its celebrated photograph – all of these against the War Office grabbing Welsh land. The Peace Pledge Union was indebted to him for his support and leadership and Gwynfor published a number of booklets and pamphlets such as They Cry Wolf and Wales Against Conscription. Then, in 1973, he delivered his famous lecture in the Temple of Peace, Cardiff – Non-violent Nationalism. He was just as supportive of CND as well, and spoke most strongly time and time against the Vietnam War, offering himself as a human shield in Hanoi in 1968 – but his group were refused admission – nevertheless the act as typical of a man who could not stand by and watch such slaughter. Dafydd Elis Thomas says of him in one of the Peace Pledge Union’s newsletters: “This great soul was born in the most violent century in the history of the world. In the darkness of the warlike twentieth century his life was a beacon.”

FIGHTING FOR THE LANGUAGE

Gwynfor played a vital role in the campaign to secure a radio service for Wales – in 1939 the BBC removed programmes about Wales completely. In the National Eisteddfod in Llandybie in 1944 Gwynfor gave a lecture to a packed chapel on Radio In Wales. The lecture was published in Welsh and in English and 10,000 copies were sold! Gwynfor argued for devolution in the field of broadcasting, and to cut another long story short – this was successful and he was elected as a member of the BBC’s Welsh Advisory Committee in 1946. Although it would be a long battle, BBC Wales together with Radio Cymru and Radio Wales were secured later on.

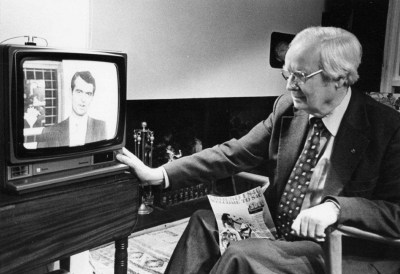

Victory – the first day of the Welsh language television service on S4C, 1982

By the mid 1950s Gwynfor could also see that the arrival of television also meant a revolutionary change in the system of communications that posed a major threat to the Welsh language and culture. He pressed the idea of Welsh television, but the government did nothing to help, and he did not succeed in fulfilling his aim. Gwynfor made an important Commons speech in 1969, calling specifically on the government to establish a Welsh Channel, and you know about that campaign in the 1970s. The story of the campaign to ensure the setting up of S4C is one that will always be associated with Gwynfor and his intention to fast after the Tory Government broke its pledge – that story would be another lecture as later this month we mark the 30th anniversary of broadcasting on C. Apart from the non-stop leadership Gwynfor provided for every aspect of the language struggle, there was his campaign for a Welsh language College. He became a member of the University Court and in 1951 he proposed setting up a Welsh College, with a committee set up to consider the idea. Everyone was opposed apart from Gwynfor, who again in 1953 prepared a detailed memorandum showing the need for this type of college. He carried on the struggle in following years – another campaign in 1973 and then in 1986 when addressing the first Welsh language graduation ceremony organised by the Welsh Students Union in Aberystwyth. He showed great determination and unswerving drive – and by now the Welsh College exists, with its administrative centre in Y Llwyfan here in Carmarthen. THE FAMILY MAN “He would never tell us or our children – ‘go away, I’m too busy, and he never waved a finger at us to chastise us. His patience with the children was limitless.” Those are the words of his daughter Meinir. The family moved from Wernellyn to Talar Wen in 1953 – “Talar Wen was my father’s wedding present, postponed for fifteen years” said Gwynfor. “Everything used to build the house was from Wales and Rhiannon’s brother Dewi Prys designed it.”

Gwynfor and his family

Gwynfor and his familyThey had seven children and in response to a journalist Gwynfor said that his favourite Biblical saying was – “Be fruitful and multiply and fill … the earth”. He loved playing with the children – and dressing up as Auntie Jini, fooling the grandchildren into believing she was a half sister from America. He also loved walking with the children, and his favourite place was y Garn Goch – the mountain where his ash was scattered and where a memorial stone stands at the foot of the hillside. Like his father, Gwynfor was musical and liked to play the piano. According to his brother Alcwyn, Gwynfor would tend to go to the piano when he faced pressure, and when playing he would be able to relax. Gwynfor and Rhiannon moved to another Talar Wen in Pencarreg near Llanybydder in the summer of 1984 when he retired. A big farewell supper was held in Llangadog hall for the community to pay tribute to a couple who did so much for the Welsh traditions of the area for a period of 45 years. When 17 Plaid Cymru members were elected to the first National Assembly in 1999 they all came to Pencarreg to see Gwynfor and Rhiannon. Other visitors included Winnie Ewing with Rhodri, Cynog and Roy Llywelyn. On the day before Gwynfor celebrated his 90th birthday a piece about him was carried in the Western Mail. He headline read – ‘Pacifist giant of Welsh culture whose place in history is secured – Wales celebrates 90 years of Gwynfor’. “Gwynfor Evans has been described as ‘one of the greatest souls of the 20th century. Alongside Lloyd George and Aneurin Bevan he is one of the last century’s three greatest Welsh politicians. But he arguably stands alone and ahead of them all in the measure of his influence and is one of the few people from any era recognised solely by their Christian name. “Gwynfor’s place in history is secure, and not just through his achievements and influence but his public acclaim. He was chosen by readers of Wales on Sunday as Millennium Icon ahead of Lloyd George and Aneurin Bevan, voted Welsh Person of the Millennium ahead of Owain Glyndŵr by readers of Y Cymro and was reader’s choice in the Western Mail’s Person of the Millennium Award. They were popular endorsements of the greatest living Welshman of the 20th century.” Gwynfor appeared in public for the last time at the 2,000 National Eisteddfod in Llanelli, where he received the Worldwide Welsh Award for a lifetime’s work for Wales. The ceremony was full of emotion, with a packed pavilion honouring this very special man. And to conclude, I would like to quote Professor Geraint Jenkins in his address to the Gymanfa Ganu we held in Capel Heol Awst to mark Gwynfor’s life soon after he died. This is what he said – “Set about praising and publicly honouring Gwynfor’s name by erecting a fitting monument to him. What better place could there be to place a fitting memorial than here in Carmarthen, where he experience his big moment on 14 July 1966 so that your children and your children’s children can come here to admire one of the great figures of our nation.” And as you know that work is now in hand, with the intention of realising a monument by 2,016, the fiftieth anniversary of his great victory in 1966. Gwynfor Richard Evans died on Thursday morning 21 April 2005 at the age of 92 in his home in Talar Wen, Pencarreg. Rhys Evans says: “Gwynfor wanted to return to Garn Goch, to the soil, the land of Wales where his politics had taken root. Nevertheless, as his ashes blow in the wind, his legacy survives.” And Dr Geraint Jenkins says: “His aim was to build a nation that was free, responsible and confident, by restoring the memory of its people and strengthening its will to live – and we should remember him as ‘Llusernwr y canrifoedd coll’, the illuminator of the lost centuries. Time after time Gwynfor was there to stand in the breach – his life reflected the history of Wales 1940 on. The foundation of Gwynfor’s life was his Christianity and his pacifism.” The last sentences in Rhys Evans’ substantial volume are: “No one did more than Gwynfor in the twentieth century. It is not the Welsh-speaking Christian Wales that Gwynfor dreamed of, but it is still Wales. Wales, the nation he loved with such passion, has survived, despite it all.”

Peter Hughes Griffiths

JE – Architect of Plaid Cymru Address by Dafydd Williams

During the annual conference in Llandudno in September 2011, the Plaid Cymru History Society organised a meeting to commemorate the life of JE Jones, who served as party General Secretary between 1930 and 1962. This is the address by the Chair of the society and one of his successors in the post, Dafydd Williams.

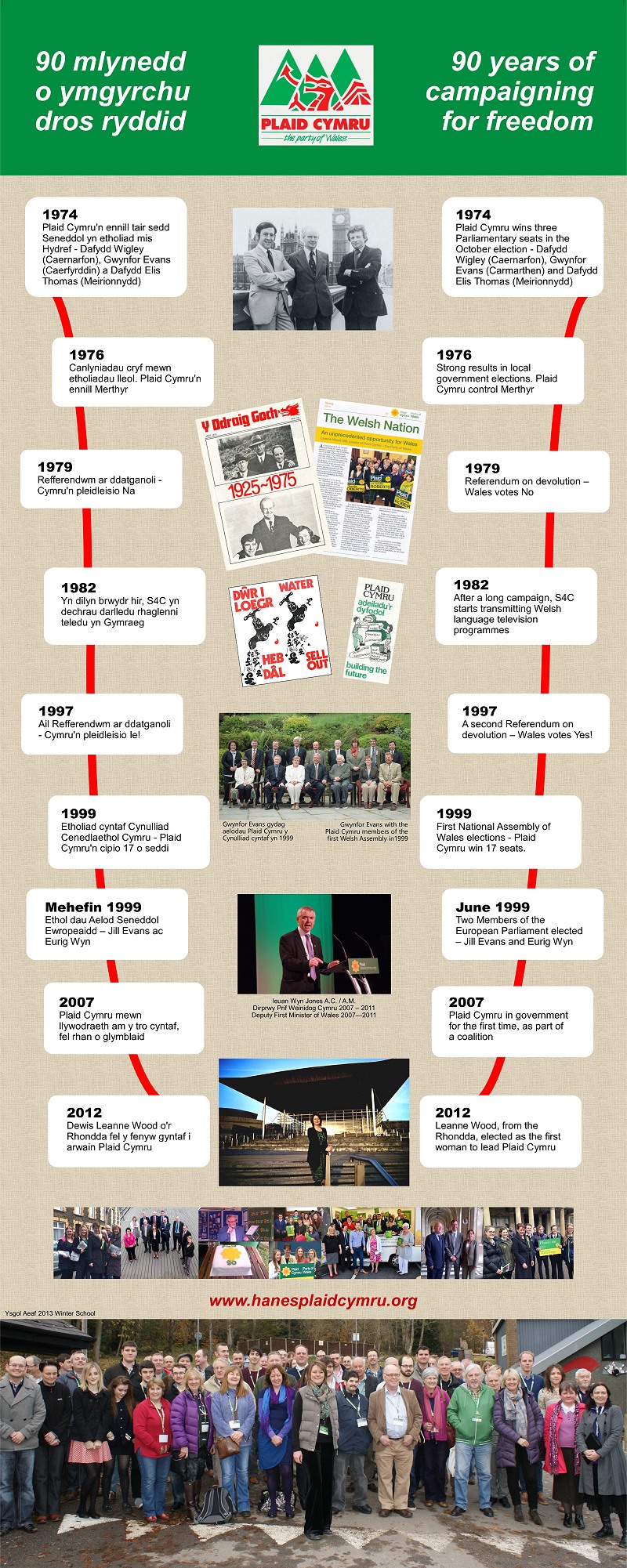

One of the earliest photographs from Plaid Cymru’s archives shows a group of people gathered at the 1927 Summer School at Llangollen. At the end of the front row is a young man with curly hair, his face full of energy and enthusiasm. Naturally I never knew the strong, young JE Jones who delighted in day-long expeditions across the mountains of Wales. By the time I met him in the mid 1960s, his robust good health had left him – a consequence, some said, of his incessant overwork for the cause of Wales. But his spirit and dedication to his country were as strong as ever.

John Edward Jones was born in December 1905. That meant he was ten years or so younger than Saunders Lewis and Lewis Valentine, and unlike them part of the generation that escaped the horrors of the First World War. His childhood home lay near the village of Melin-y-Wig, a hilly district about seven miles from Corwen and ten from Ruthin, the stamping ground of Owain Glyndŵr.

From the high ground behind the family farm, Hafoty Fawr, a clear day would give you a 360-degree view of the mountainous heartland of Gwynedd, Clwyd and Powys, which he describes in a lyrical passage in his important book Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid – half autobiography, half history of Plaid’s first forty years. It would be fair to describe JE as a patriot from his earliest days, drawing inspiration from the mountains of his birthplace: in fact he describes himself as ‘Mab y Mynydd’, the son of the mountain.

Before he had reached his first birthday, JE’s father died; but somehow his mother kept the family farm going with the help of her family, JE’s two brothers in particular, both of whom left school at 14 years of age. JE himself was to tread a very different path, despite his deep attachment the rhythm of agricultural life and the rural culture of Melin-y-Wig, with all its concerts and eisteddfodau. He won his way to Bala Boys Grammar School, Ysgol Tŷ Tomen, staying in Bala during the week. For all that Bala was a solidly Welsh-speaking area, everything in the school was in English. Was it this that fired up his lifelong support for Wales and the Welsh language? He tells the story of how he and a friend intervened to prevent a teacher picking on one of their fellow pupils who spoke little English – and succeeded in putting a stop to it. Then during the summer holidays in August 1923, after delivering eggs and butter to the village shop, he read a newspaper account of the meeting in Mold of a new movement with the odd title of ‘The Three Gs’, an acronym for y Gymdeithas Genedlaethol Gymreig, the Welsh National Society. This was one of the three groups that later came together to form Plaid Cymru; and a year or so later JE was to join it, as a first year university student at Bangor, where he studied Welsh, English and Mathematics, which he described as a “somewhat unusual combination”.[1]

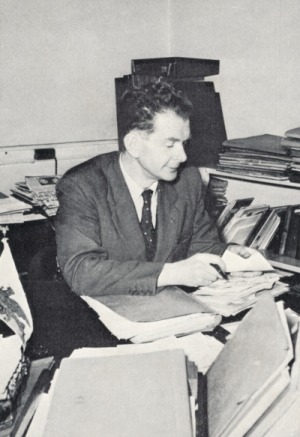

JE Jones – Architect of Plaid Cymru in his office in Caernarfon

Soon after, he heard reports of the launch of Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru in Pwllheli, and in October 1926 he attended a Plaid meeting in Caernarfon, filling in a membership form there and then. The forms were collected by HR Jones, a thin young man with a pale complexion: little did JE know that in a few years’ time he would be taking his place as Plaid Cymru’s general secretary. Within a month, a Plaid branch had been set up in the college in Bangor, with JE as secretary; by the summer it had nearly 80 members. JE stood as the party’s candidate in a mock election in November 1927 – and after a barnstorming campaign, he won! Could this have been Plaid’s first ever election victory? “I learnt then,” he was to say, “that it was easier to win over intelligent English people than a number of servile Welsh individuals.”[ii]

Once his University days were over, it was time to look for work. With a depression already looming, he applied for a teaching post in east London – and got it, one of four appointments out of 60 candidates. It seems most of the interview was spent discussing self-government for Wales! In no time at all, he had become secretary of Plaid Cymru’s London branch, although he also found time to play football for London Welsh Second XI and tennis during the summer.

Then came a decisive turning point in the young teacher’s life. After a long illness, HR Jones, the main driving force behind the foundation of Plaid Cymru, died. Despite fears about being able to afford it, the party leaders decided that a full-time successor had to be appointed. JE, together with a friend, the Guardian journalist

Gwilym Williams, decided they would both apply – using exactly the same wording, and giving each other’s name as a reference! JE was appointed – to a post he loved: “I was Secretary and Organiser of the movement for Welsh freedom from December 1930 until May 1962, when the old heart said it could take no more.”[iii]

It is interesting to compare the two Jones, HR a JE. One footnote, perhaps trivial but worth noting, is this: both of them succeeded in restoring the traditional names of their home communities; from Nasareth to Deiniolen in the case of HR, Cynfal to Melin-y-Wig in the case of JE. There was certainly a strong similarity in one aspect of their characters – an unswerving devotion to the cause of Wales and the Welsh language, and a vision of their country as taking its place among the world’s fully fledged nations. To which we can add the readiness to work without stop. I am grateful to Dewi Rhys, JE’s son, for these recollections of his father (my translation): “He was never idle. He would be on his feet about 5 every morning – either on the little typewriter, or in the greenhouse where he would ‘relax’ by transplanting hundreds of small plants, with the garden a sea of colour every summer. He was delighted to hear people making complimentary comments about the garden as they passed by. Even on holiday, he wasn’t idle. He would write diaries and bind them together as book after we came home.”[iv] Such commentaries were to form the basis for Tro i’r Swistir, the book he later wrote about their visits to Switzerland.

But the differences between the two are also revealing. As ever, JE is full of praise for his predecessor but he could not but observe the fact that party branches and rhanbarth organisations had languished and ceased to exist during HR’s illness: “To all intents, I was obliged to rebuild Plaid Cymru all over again.”[v] Plaid’s principal historian, D Hywel Davies, goes further, describing HR in these terms: “a restless visionary, longing for vigorous action on behalf of Wales rather than a desk role”. By contrast, JE “though prepared for radical action, was blessed with a painstaking nature more fitted to the task of careful organisational planning”.[vi] Hywel Davies also points to JE’s background as a University graduate and qualified teacher, concluding that this made him more comfortable among the membership Plaid was attracting.

JE took up his post on 1 December 1930, working from a small office in Caernarfon adjacent to the Pendref hotel where he took lodgings. What followed was a 32-year ‘stretch’ in which he became the lynch pin of party activity. JE soon established himself as the centre of communication and information for the party; and Plaid Cymru became noted for the quality and quantity of its publications. In the first four years of existence, it had published just one substantial pamphlet, Saunders Lewis’ Principles of Nationalism. Once JE took up the reins of office, Plaid began producing a steady stream of literature. It is worth noting that this output included several solid works on economic policy – including The Economics of Welsh Self-Government by Dr DJ Davies (July 1931) and two by Saunders Lewis – The Case for a Welsh National Development Council (1933) and Local Authorities and Welsh Industry (1934). These publications, supplemented Y Ddraig Goch, which slightly preceded the foundation of Plaid Cymru, and its English-language counterpart, Welsh Nationalist, set up in 1932.

The emphasis was very much on selling and sales campaigns rather than giving away; although JE developed the habit of what he called ‘meithrin tawel’ (quiet cultivation), sending the latest publication with a friendly covering letter to a selected range of prominent people – the artist Augustus John was one he said joined the party as a result.[vii] I recall (to my shame) Gwynfor Evans pointing frequently to the relative dearth of Plaid publications during the 1970s and 1980s by comparison with JE’s term of office.

Then there is PR. While persuading others to produce detailed publications, JE himself was master of collecting the telling quote and the killer fact, which he described as ‘bwledi’ – bullets. This led on naturally to press communications, in which he proved expert – both in crafting press statements and cultivating journalists. I like his restrained critique of some of his fellow Nationalists in this area: “I found one of the most difficult things, in the early years, was to educate our local officials – secretaries or correspondents – to write ‘effective pieces’ for the Press and to develop friendly relations with journalists. But that came, over time.”[viii] JE could have taught 21st century spin doctors a trick or two: his advice on using the Press remains as true today as ever, for all the changes brought by the age of the internet, Facebook and Twitter.

One early priority was building the party, from the tiny handful he inherited in 1930. This proved painfully slow, although JE set about the task in his typically systematic way, moving from county to county, badgering members to establish county committees and in due course branches. Saunders Lewis was characteristically acerbic about the rate of progress: at the end of 1935, after praising JE’s work, he asked: “But where are his disciples? An organiser of the same calibre in every Rhanbarth Committee would transform the course of Plaid Cymru.”[ix]

Here it’s worth recalling some home truths. Plaid Cymru was still small. It was also (in terms of the age of its members) overwhelmingly young. Because it was small and young it was also poor, very poor. This partly explains how few elections it fought – one Parliamentary seat in 1929, two in 1931 (Caernarfon county and the University of Wales), back down to one in 1935. By the way, 1935 was the first election for Plaid to use canvassing – a technique JE adapted from his contacts with parties in Denmark, Ireland and England. Local elections contested were also few and far between. Perhaps poverty isn’t the whole truth – the indefatigable DJ Williams complained bitterly at the lack of fighting spirit, describing Carmarthenshire county committee as “a dead body”.[x] This was 1935!

One technique JE pioneered to tackle Plaid’s financial problems was the St David’s Day Fund, based on the experiences of Fianna Fáil. The first appeal, in 1934, raised the princely sum of £250! Building party membership and funding went hand in hand with fighting campaigns – on a whole range of topics. Just one example – shortly after taking up his post JE launched a campaign to popularise use of the Welsh flag in place of the ubiquitous Union Jack. The first target was Caernarfon castle, whose Constable was none other than David Lloyd George. His opening gambit was typically modest, scarcely capable of rejection – simply equal status for the two flags on St David’s Day. A letter forwarded by Lloyd George to the Minister in London elicited a contemptuously negative response – just what JE was after of course. He promptly published it!

On St David’s Day 1932, clad top to toe in motor cycle gear, JE paid his sixpence and made his way to the top of the Eagle Tower, joined by three other conspirators, including Lloyd George’s nephew, WRP George. There they lowered the Union Jack, raised the Ddraig Goch and then stapled the ropes to the flagpole – JE’s planning of course included a hammer and staples in his rucksack. The spectacle of a large red dragon flag on the tower prompted cheers and a quick rendition of Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau from a crowd below; although the local constabulary soon appeared, and before long the Union Jack was back in its place. Later in the day, however, and quite independently, a group of Plaid students from Bangor showed up on the back of a lorry. They too got up to the Eagle Tower and succeeded in smuggling out the offending Union Jack, which met an unfortunate fate on the Maes.

The following St David’s Day saw a government U-turn. A large Draig Goch was raised as high as the Union Jack, and the ceremony was performed by none other than David Lloyd-George. Soon afterwards, the Welsh flag would fly from all government buildings on 1 March; and JE saw to it that party branches pressed the local authorities to follow suit. He then arranged production of more flags, selling them at a tidy profit.

Other campaigns involved moves to raise the status of the Welsh language – for example, shaming the Post Office into accepting prepaid envelopes with Welsh place names – building up to the successful drive to ensure Welsh language programmes on the BBC. A common theme in all these endeavours – and many more – was careful planning and a holistic approach – never missing out on an opportunity for good PR. This care was evident than during the burning of the Penyberth bombing school in September 1936, an operation remarkable for its secrecy and meticulous attention to detail. This included a spy – the young Alaw Non Rees, who from her upstairs window in Llanbedrog kept tabs on how much timber had arrived on site.

JE was one of seven people who played a direct role in the operation – he walked part of the way back to Caernarfon along the railway to avoid detection. The following morning in his lodgings he received a letter from Saunders Lewis – apologising for not informing him about the burning! It was of course an alibi – the Plaid leaders could not afford to have their office closed down and their organiser behind bars at such a crucial moment. JE remained free to organise nationwide protests. Dewi Rhys recalls seeing the bundles of telegrams of support sent to the Penyberth Three – Saunders Lewis, Lewis Valentine and DJ Williams – telegrams that JE had organised: by law they had to be delivered, even during a High Court trail, helping to maximise the impression of public support.[xi] He also arranged what I believe must still rank as the biggest ever party rally – a crowd of 12,000 welcomed the Penyberth Three back to Caernarfon from Wormwood Scrubs.

Penyberth and the two High Court trials that followed proved a pre-War high water mark for Plaid Cymru. JE argues that much of the new support the party won was dissipated by opposition to the coronation of George VI, a decision taken during Saunders Lewis’ prison sentence and a rare spell of sick leave for himself. Opponents also saw Lewis’ conversion to Catholicism as a chance to smear Plaid with the taint of fascism. The outbreak of War posed a huge challenge – even a mortal threat to the party’s existence, as Saunders Lewis openly admitted at the time. Yet somehow Plaid Cymru carried on, and even grew in influence as the war went on. The party hit back at its detractors with vigour and confidence. It resisted conscription, JE facing six separate courts and tribunals over three years, and doing so with some style. And it fought tooth and nail to save 40,000 acres of land in the Epynt range from seizure as a Ministry of War firing range. So in April 1940, JE found himself walking the mountains again, visiting every farm endangered; but London had its way.

Planning post-War election strategy – the SNP’s first MP Dr Robert McIntyre joins Plaid leaders in 1945

From 1942 the tide was clearly turning in the party’s favour. A by-election for the University of Wales seat saw Saunders Lewis take 23 per cent of the vote: JE notes (with satisfaction) that he was described as ‘cunning’ for his role as the “assiduous, astute and untiring agent”.[xii] And he had another reason to be happy. In 1940 he had married Olwen Roberts, secretary of the Caernarfon rhanbarth, the ceremony performed by Lewis Valentine. Two children, Angharad and Dewi Rhys, were to follow.

By 1945, Plaid Cymru emerged stronger than ever. For the first time it could lay some claim to be an all-Wales party, fighting seven seats in the general election. In the summer it chose a new leader, the 33-year-old Gwynfor Evans, and he and JE were to form a cohesive team for the next decade and a half. In fact, says Hywel Davies, it is from 1945 rather than 1925 than Plaid can be regarded as a political party, albeit still a party in embryo.[xiii]

Once again it fought a Ministry of War land grab, this time in Trawsfynydd, Meirionnydd and this time successfully. Again JE provided organisational flair: the police and army were outwitted by a diversionary group while the main protest used back lanes to stage a two-day blockade. By 1950 Plaid Cymru was fully engaged in the Parliament for Wales campaign and JE organised a series of rallies which would be held annually for a quarter of a century. The 1953 rally was one of the biggest seen in Cardiff. Unusually he took the chair – but his real input was planning and implementation. The build-up included a relay of torch bearers running from the Owain Glyndŵr Parliament House in Machynlleth to Sophia Gardens: JE ensured the speeches and messages went on long enough for the ensuing procession to be seen by crowds leaving Cardiff Arms Park.[xiv] He was also involved in the defence of the Tryweryn valley although by now he had more assistance.

JE chairs the 1953 Parliament for Wales rally in Sophia Gardens, Cardiff

Of course JE Jones was not without his critics. Some felt that someone of his background could not relate to the industrial, non-Welsh-speaking communities of south-east and north-east Wales. I think his track record shows otherwise. Tros Gymru is full of references to the need to appeal to those who do not speak Welsh. JE supported the move of the party’s office from Caernarfon to Cardiff in 1946 – in fact he personally located premises in 8 Queen Street. Dewi Rhys recalls that the official opening took place on 1 March, the day of his birth, with his father trying to be in two places at the same time – as usual![xv] His work enabled Plaid Cymru to spread its wings in the south after the war. For his part JE always showed a great reluctance to criticise fellow Nationalists. Here is one rare example: after praising the leadership of Saunders Lewis, he allowed himself this one comment: “But he did develop a tendency towards a mistaken prejudice sometimes against certain types of people; for example, he could suggest, about someone quite as courageous as himself, that pacifism was cowardice.”[xvi] The ‘someone’, of course, has to be Gwynfor Evans.

Others felt he was too close to the party elite; especially at times of strain within the ranks, as for example during the Tryweryn campaign. By 1950, the now ex-president Saunders Lewis was privately critical of what he called JE’s ‘parchusrwydd’, respectability, which he contrasted unfavourably with the militant tactics of the Welsh Republicans.[xvii] But JE was by his nature a loyalist, committed to supporting Plaid Cymru and its chosen leadership through thick and thin, whatever that might demand. He had proved himself more than ready for radical action: his willingness during the war years to oppose conscription as a nationalist and face prison demonstrates that. The ‘respectability’ of which Saunders Lewis complained was that of Plaid Cymru rather than JE: it reflected the determination of Gwynfor Evans to put post-War Plaid on course to be a truly all-Wales party rather than a nationalist pressure group.

Looking back, what is striking is JE’s willingness and ability to continue at his post, for all the problems and pressure Plaid Cymru faced. Could the party have held together during the 1930s, the 40s and the 50s without JE at the helm? Perhaps, but I find it hard to imagine how. His tombstone in Melin-y-Wig bears the dedication ‘JE Jones, Pensaer Plaid Cymru’ – a fitting tribute to the architect of Wales’ national movement.

JE Jones (1905-1970) is buried in the cemetery opposite the chapel in Melin-y-Wig, Denbighshire. A plaque on the wall of the former village school he attended also commemorates his life.

[1] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid. (Gwasg John Penry, Abertawe, 1970), p.37.

[ii] Ibid, p.40

[iii] Ibid, p70

[iv] Ebost i’r awdur gan Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, Mis Medi 2011.

[v] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.97.

[vi] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party 1925-1945: A Call to Nationhood (University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1983), p.187.

[vii] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.88.

[viii] Ibid, p.95.

[ix] Ibid, p.113.

[x] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party, p.204.

[xi] Email to the author by Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, September 2011.

[xii] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.276.

[xiii] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party, p.268.

[xiv] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid. p 307.

[xv]Email to the author by Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, September 2011.

[xvi] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.155.

[xvii] Emyr Hywel (Editor), Annwyl D.J. Llythyrau D.J., Saunders, a Kate. (Y Lolfa, Talybont, Ceredigion, 2007), p.182.

A Bee or Two in my Bonnet – Emrys Roberts

In the beginning … D.Hywel Davies

PLAID CYMRU HISTORY SOCIETY, MARCH 25, 2011

[TRANSLATION FROM WELSH]

IN THE BEGINNING …

By D.Hywel Davies B.A., M.Sc.(Econ.)

AS is appropriate for the inaugural meeting of the Plaid Cymru History Society, I wish to take you back to the earliest period in the history of the formation of the movement. But not to the famous event that was held in Pwllheli in 1925 but to another one held in Caernarfon in 1924. I’m afraid that I can’t offer a much more exciting location: the Maesgwyn Temperance Hotel was the place arranged in Pwllheli; the Queen’s Café is the best that I can offer you in Caernarfon.

It is Saturday night the twentieth of September, 1924, and quite a number of people from Caernarfon and district are walking in the direction of the Queen’s Café in the old heart of the town. It has been a year of political excitement – namely the formation of a British Government for the first time by the new Labour Party under the leadership of Ramsay Macdonald back in January. It’s a minority Government, and the talk is that there will be another General Election pretty soon. David Lloyd George has no worries about that. Caernarfon Borough is solidly behind him – and it’s certain that he is conspiring how to regain the keys to Number 10 sometime in the future. But the Labour Party is now on the rise having already achieved the status of the second party in the only Parliament they had at that time.

Britain is not the topic of conversation of those heading for the Queen’s Café tonight. Wales is the topic. The politics of Wales. A Wales without a national political body. A Wales without a nationalist movement. A Wales without sub-branches of the British parties to recognise its national status. A Wales without the Red Dragon on the towers of Caernarfon Castle.

But there is some Welsh political context. Specifically, because of its previous history as the main spokesperson for Wales at Westminster, the failure of the Liberal Party as a body to raise once more the question of devolution. The most recent development was a religious matter. The Church of England in Wales was disestablished as a part of the British state church. In its place, in 1921, the Church in Wales was established as an independent Welsh church. But with that religious devolution, it was as if the breezes had disappeared from the sails of Welsh political devolution. But not entirely.

A number of conferences were held between 1918 and 1922 to discuss devolution. They were arranged by a handful of individual Liberal Members of Parliament who invited representatives of local councils and other movements. There was very little response to the first conference that was held in Llandrindod Wells. It was agreed that ‘self-government’ would be beneficial for Wales but without it being defined. Not having received an invitation to this conference, the new Labour Party saw the whole thing as a Liberal ruse aimed at hanging on to the votes of Welsh patriots. The Labourites of south Wales declared their support for home rule in 1918 as did the North Wales Labour League in 1924. Nevertheless, as was stated by the important Labour figure David Thomas, who supported devolution, the real battle was that between labour and capital.

The most successful conference was that in 1919, again in Llandrindod Wells. It was enthusiastically agreed to call for ‘full local autonomy’, again without definition. And a Welsh Secretary of State was called for though with a smaller majority following a heated debate. The Western Mail described the agreement that was reached as ‘something in the nature of a miracle … [though it] left the question very much where it found it.’

Not much more light was provided when a small group of Liberal Members of Parliament asked the Prime Minister – the old nationalist David Lloyd George – in 1920 to create a Secretary for Wales. “Go for the big thing!” he replied, but nobody understood that. A measure was proposed by David Matthews, the Liberal MP for Swansea East, in 1921 calling again for a Secretary of State for Wales, but no one was paying attention. There were other things on the minds of the leaders of the central Liberal Party. The Labour Party in particular.

By now the Welsh inspiration was diminishing quickly. The final conference of this series was held in Shrewsbury in 1922 – ironically enough on the day of the signing of the Royal Assent for the creation of the Irish Free State. There was scant support. The few who were present failed even to support Murray Macdonald MP’s private measure, The Government of Scotland and Wales, which called for federal devolution. The Welsh Outlook magazine commented, ‘The futile Shrewsbury Conference on March 31st last and the ridiculous debate which followed it in the House of Commons on April 18th, marked the nadir of the Welsh Home Rule movement, and only a small remnant of those who supported it escaped pessimism and despair.’ Murray Macdonald’s measure failed. It was the end of an era. Devolution disappeared at Westminster.

No. Those Welsh patriots who were closing in on their cups of tea at the Queen’s Café did not have much reason for hope. But, with the enthusiasm that has been central to our movement, they would surely have responded. “Hold on! There’s an excellent group of students who have raised a great nationalist furore at Aberystwyth fairly recently. And in Bangor – there’s a student society there – The Tair G society – which is full of Welsh enthusiasm. And there’s the scholar Saunders Lewis who has kicked a hornet’s nest to annoy the respectable, hypocritical Welsh. Yes, there is hope!”

Ready to welcome them in the Queen’s Café was 24 year old H.R.Jones, a quarryman who had had to become a travelling salesman due to poor health. H.R. was from the village of Ebenezer – though he was leading a campaign at the time to bring Deiniolen back as its name. It was he who had arranged tonight’s meeting on the much greater topic of the nation’s future. H.R.Jones had been sending letter after letter to everyone he knew as patriots – far and wide, prominent and less well known. Come, he said, to set in motion an independent Welsh nationalist political movement.

H.R. was a shy man, a quiet man. But he was boiling with frustration. It was yet another conference that had particularly upset him. This one had been held during the summer by one of the small patriotic movements that were emerging briefly and disappearing like fireflies as Welsh enthusiasts sought the way forward: Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (The Welsh Language Society) – the first with that name; Urdd y Delyn (The Order of the Harp) – a foretaste of Urdd Gobaith Cymru; the enthusiastic Lady Mallt Williams of St Dogmael’s Byddin Cymru (Army of Wales) – not a weapon in sight despite its name; Undeb y Ddraig Goch (The Union of the Red Dragon) in Liverpool; Lloyd George’s brother William’s Cymdeithas Cymru Well (The Better Wales Society). This time it was Byddin yr Iaith (The Language Army) which had held its annual meeting in Llandrindod Wells. Despite its threatening title, there was nothing military about Byddin yr Iaith: members were to wear the movement’s badge, to speak Welsh as often as possible in places such as post offices and train stations, and to demand official status for the Welsh language. During the conference, another tiny movement with a big name – the Home Rule Section of the League of Welsh Nationalists – had held their own meeting. There were speeches. An appeal was issued.

H.R. was furious. He sent even more letters. It was raining H.R. letters in Wales! The Rev J.Seymour Rees was glad to receive one in Treorci. D.J.Williams was pleased when his arrived in Fishguard. Iorwerth C.Peate was delighted, though he would have a few questions. So H.R. went ahead to organise his meeting in the Queen’s Café with the aim of ‘establishing a society for young home rulers.’

It was also true that the academic and conservative Saunders Lewis – a conservative with a small ‘c’ but a pretty big ‘C’ as well! – had caused consternation only a year earlier due to a speech he gave at the National Eisteddfod in Mold. He shook long-winded patriots by calling for the establishment of camps to teach discipline. But remember that this was Lieutenant John Saunders Lewis talking, one who had served in the trenches during the Great War and who had been injured. He stated: ‘Our condition cannot be saved by a conference but by discipline and obedience. Do not seek a conference in which all the chatterboxes of Wales can deliver useless speeches, but next year form a battalion and a Welsh camp, and every Welshman who wishes to serve his country to come there to drill together for a fortnight and obey military orders so that they work together quietly and without argument, everyone prepared to obey and to be punished if he does not do so. And do this for five years, without chatter. Drilling without weapons, and so openly and without breaking the law of any country, but by this preparing ourselves to accept laws and leadership by Welshmen. If we had a hundred or fifty or only twenty in the first year to do so, this would be Wales’ most important movement since the days of Glyndŵr. I am perfectly serious’.

It was necessary for Lewis to add that last sentence. Welsh nationalists were not supposed to talk like this. But that was the kind of frustration that was to be found among the younger generation. Saunders Lewis’ particular response was unique, foreign, and he was flayed. ‘Naked stupidity,’ said the weekly Darian newspaper in the southern Valleys of his plan. ‘The most stupid of reactionaries’ was the response of the Western Mail. ‘Hotheads who propose to give the undergraduates of the Welsh colleges military training in holiday camps!’ said the South Wales News.

The only one to express similar ideas was Ambrose Bebb, Lewis’ friend and another conservative with a small ‘c’ which had larger implications. Bebb had moved on from Aberystwyth to study and lecture at the Sorbonne university in Paris. There, Bebb came under the influence of the right wing movement of Charles Maurras. He, too, was inspired to express the need for social discipline under strong political leadership in an article he wrote in 1923. With more rhetoric than reason, Bebb succeeded in linking the names of Lenin and Mussolini as the kinds of heroes that the Welsh should consider. Very quickly, Saunders Lewis and Bebb were being known as Sinn Féin people.

So, with the weak devolutionary conferences of the Liberals having failed, the new Labour Party gaining in strength, along with the inflammatory declarations of Lewis and Bebb, the Queen’s Café crowd had a quite a lot on their plates.

And there they are arriving at the Queen’s. Among the youngsters is Gwilym R.Jones, who would later become Editor of the important weekly newspaper Y Faner. This is how he described the assembly: ‘There were some forty of us in the meeting. There were teachers, quarrymen, ministers, a doctor – and one pale salesman,’ namely H.R.Jones himself. ‘This salesman had brought together the meeting, but he said very little. Nervous, inarticulate, bungling. He wanted an “army” to defend Wales and the language.’ In an effort to have a person of status at the helm, the patriotic doctor, Dr Lloyd Owen of Cricieth, chaired the meeting. But H.R. was the catalyst for the event.

H.R.Jones was considered an expert on the history of Ireland. It must be remembered that the bloody Irish struggle to achieve freedom from the bonds of London was the background to all the home rule discussions in Wales following the end of the Great War. According to his friends, H.R.’s view was that similar radical action, including violence, was also needed to promote the cause of Welsh nationalism. Gwilym R.Jones would later quote him stating categorically, “We will never awaken a nation that has been sleeping without sacrificing more. We must suffer … blood must be spilt. Our movement is too tame, and we are too cowardly.”

Saunders Lewis would say of him, “H.R. was the only one in our midst to whom one could imagine Michael Collins giving a post, one who could not be shocked nor frightened, one who would do anything, without caring about the consequences, if that would bring the freedom of Wales closer.”

With all of this in the background, Dr Lloyd Owen declared from the chair that though perhaps a ‘militant attitude’could be welcomed to the new nationalist movement, there would be no place for ‘violence.’ His comment was supported by at least one other who roundly criticised any suggestion of what was described by him as ‘Russian or Irish methods.’But one of H.R.’s associates, Evan Alwyn Owen, argued in return that ‘introducing a little Sinn Féin’ to the movement could be helpful. Another friend, the journalist Gwilym Williams, went as far as declaring that he supported ‘marching with guns’ and that he agreed with ‘the philosophy of [Patrick] Pearse.’

No further light was shed in the Queen’s that night, however, on the question of methods. Neither was there detailed agreement regarding what kind of home rule would be of benefit to Wales. Nevertheless, it was agreed to establish a new movement. Reflecting the feeling that what was essential was a completely committed society, it was decided to name it ‘Byddin Ymreolwyr Cymru’ (the Welsh Home Rulers’ Army) and to adopt an oath of loyalty that might ensure organisational effectiveness. The emphasis, however, was on political methods. In a note for the press, H.R.Jones said, ‘We aim for home rule today not in the ruins of the United Kingdom but through arguing rationally for our rights. We, the oldest nation in Europe, demand a Parliament and a home, by which will be organised a way for our nation to develop its life along Welsh lines.’

The fact that the Queen’s Café meeting was a public event meant that the press had plenty of material with which to be critical. The North Wales Chronicle was scathing: ‘Those present,’ it said, ‘outnumbered the famous tailors of Tooley Street, but, like the latter, their ambition has brought a touch of comedy into a movement which has as much attraction for faddists as a lamp light has for moths.’

The local Herald Cymraeg was more disappointed than aggressive: ‘The meeting of home rulers of the district that was held in Caernarfon on the Saturday before last was of no help to the movement; rather to the contrary. It was entirely irresponsible and childish. It is a great shame to move ahead with such an important movement without proper preparation, and without ensuring influential speakers.’

‘Childsplay,’ complained the Darian in the south.

Gwilym R.Jones referred to what he described as bungling. Nevertheless, a meeting was held, and a public meeting at that. Being so open – inviting people to the Queen’s Café – was a very different kind of procedure to that of another nationalist movement which had been established at the start of the same year. That was created by Saunders Lewis, Ambrose Bebb and Gruffudd John and Elisabeth Williams in Penarth, in the privacy of the Williams family home. Very few knew about it because it was a secret movement. Y Mudiad Cymreig (the Welsh Movement) was the name whispered quietly among its handful of supporters. Their aim was to remain secret for an indefinite period. That would not prove difficult because they decided to use Breiz Atao, the paper of the Breton nationalist movement, as the prime medium for their ideas. Gruffudd John Williams later said, ‘The French and Breton turned many people away.’ At least the Welsh Home Rulers’ Army had made it into the headlines in the press, and, as is claimed, all publicity is good publicity.

The Queen’s Café, however, was a process not an event. H.R.Jones had set in motion an activity that would be of central importance in the development of our national movement. There was a great deal of discussion regarding the first night at the Queen’s. The problem was that there had been no clear agreement on objectives. Indeed, the Welsh Home Rulers’ Army almost came to an end, just another small, short-lived society. Some argued in favour of merging with the Bangor university student movement, namely the Tair G (the Welsh Nationalist Society). But this was opposed by the Home Rulers’ treasurer, Evan Alwyn Owen. Evan’s aim, like that of H.R., was to establish an independent nationalist party. It was agreed to meet again at the Queen’s Café on December 20 to discuss matters further. On that occasion, Evan proposed that the title Welsh Home Rulers’ Army should be dropped in favour of Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru – the Welsh National or Nationalist Party. He said that this party should raise funds, adopt parliamentary candidates, cooperate with nationalists in Scotland, and declare that Welsh membership of the League of Nations was its objective. And so it was agreed. Three months after it was established, the Welsh Home Rulers’ Army disappeared being reconstituted immediately as the Welsh National/ist Party. The place of the Queen’s Café was safe, well fairly safe, in the history books.

The Rev Lewis Valentine M.A., a Baptist minister, was chosen as President of the new National/ist Party and H.R.Jones, of course, became its Secretary. H.R. proceeded at once to try to attract more patriots from all parts of the land to join the Blaid Genedlaethol. It appears that he had heard something of the existence of the shy Mudiad Cymreig in the south, and Saunders Lewis duly received one of his letters. Wasting no time, the small, new, independent Plaid Genedlaethol began with its activities which were entirely political in nature. The Blaid protested against the Government’s aim to split up the Central Welsh Board of Education and to close the regional office of the Department of Pensions in Cardiff; it called for Welsh speaking judges for the courts of north Wales; politicians were contacted calling on them to support Welsh home rule. Central to the new Plaid was the idea that the government of Wales should be organised with the nation as its basis and that the Welsh language should be accorded respect. Specifically with regard to linguistic considerations, the pioneering fact was that Welsh was the language of this new political party, formed as it was in Caernarfon. It was through the Welsh language that it was established and began its campaigning.

Central to everything now was the need to expand membership and to place the Blaid on a national footing. The discussions between H.R.Jones and Saunders Lewis were all-important in that process. It was no easy matter to deal with Saunders Lewis. At this early stage, he insisted on a full clarification with regard to two fields of policy in particular before agreeing to join the Nationalist Party, namely regarding the status of the Welsh language and the mode of political action.With regard to language status, Lewis agreed that ‘Gorfodi’r Gymraeg’ [trans. Welsh being made compulsory] should be the language policy, as H.R.Jones had noted, but he insisted that this had to mean that Welsh would be the administrative language of local councils, and the language of schools. With regard to the nature of political action, Saunders Lewis also agreed with the aim of ‘Breaking every link with the political parties of England and Wales.’ But he went further. He insisted as well that all links should also be broken with the ‘English Parliament’ through a declaration that the Blaid would choose to work solely through the local councils of Wales. ‘Nothing will ever come to Wales through the Parliament of England,’ he said, ‘Now, if you fully adopt these two principles, I will join with you immediately.’

H.R.Jones was not one to delay. Before Saunders Lewis received a response, there was a leaflet in his hand declaring that he was already vice-president of the new party. A furious Lewis demanded an explanation. But to his friends in the secret Mudiad Cymreig, he soon stated his satisfaction that all their ideas had been accepted. They could work like a‘bloc national’ – in Saunders’ French – within the new party that had appeared so unexpectedly, so ensuring that it kept to their principles. ‘As you see,’ he said, ‘without them knowing, they are all members of our movement.’

One other matter remained. Saunders Lewis insisted that a meeting should be held to place the Blaid Genedlaethol on a national basis. The Queen’s Café, Caernarfon, had performed the inaugural miracle. Saunders Lewis would comment, ‘I believe it correct to say that H.R.Jones established the Welsh Nationalist Party.’ H.R. now went ahead to arrange a small, private meeting for seven* representatives to meet at the Maesgwyn Temperance Hotel, Pwllheli, during the National Eisteddfod of August 1925. But that’s another story.

*Only six made it to the Pwllheli meeting, D.J.Williams having missed his train.