Saturday, 21 June, 2025 a Rally was held in Pwllheli to celebrate 100 years since Plaid Cymru was formed.

Address by Kiera Marshall at the Pwllheli Rally 21 June 2025:-

It is truly an honour to be here today – to celebrate 100 years of Plaid Cymru. A century of standing up for Wales.

For our language,

For our communities,

and for our future.

Our party was founded on two simple but powerful principles that remain at our core today.

The first: Wales should govern itself. Home rule or self-determination. The belief that decisions about Wales should be made in Wales, by the people of Wales. A belief that other parties still, after all this time, still struggle to understand.

The second principle is our language. Cymraeg. The right to live in our in language. And this is deeply personal for me. As someone still learning Cymraeg, it is a particular honour to say this clearly: That the role of Plaid Cymru in the fight for the Welsh language over the last 100 years cannot be overstated.

Pwllheli and this part of Wales hold special significance for me. Usually I’m here when I’m visiting Nant Gwrtheyrn, learning the language that should have been mine from the start. The last time I was there, my tutor was one of Lewis Valentine’s great-grandchildren. A reminder of how history lives on in the everyday and how our work today builds on the foundations laid a century ago. While we have come so far, there is still much work to do.

I went through the entire Welsh education system and left unable to speak Cymraeg. That isn’t just my story but the story of a system that is still failing our young people.

Our Senedd, though powerful in principle, is still limited in practice. It’s only as old as I am. Our democracy is young and there are people who want to see it weakend and even undone. And still, we are denied the right to shape our own future, with no control over so many vital areas that shape our daily life in Wales.

But our future is bright as we look ahead to the 2026 Senedd elections. Today is a moment to reflect on a century of Plaid Cymru’s achievements, the political force we’ve become, and the future we’re ready to shape.

From S4C, to the Welsh Language Act, to the establishment of our National Assembly, now Parliament… We have led the way, We have built the foundations, And we have been the engine of Welsh nation-building.

Year after year, campaign after campaign, election after election, We have grown, we have fought, and we have delivered.

As we look back, I want to shine a light on those whose work can be often overlooked: the women who helped build this movement.

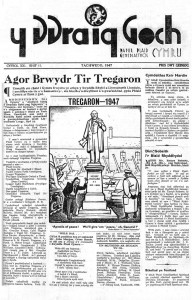

Tomorrow, I hope to visit Cae’r Gors, the childhood home of Kate Roberts. Kate was one of the early pillars of Plaid Cymru. She became the first chair of our women’s section that lives on in women I’m honoured to know and she edited the women’s page of Y Ddraig Goch. She gave voice to those who were too often unheard.

I’ve also recently learned of Elizabeth Williams. It was her home in Penarth where a new Welsh Movement was formed in 1924. She documented its growth until it merged into what would become Plaid Cymru here in Pwllheli in 1925. When she died, she left her home in Gwaelod y Garth to the party.

And now today, I stand as a Plaid Cymru candidate for Caerdydd Penarth, the very constituency that stretches from Elizabeth’s home in Penarth to her home in Gwaelod y Garth.

Her legacy lives on in our fight today.

And that fight led to another woman who shaped our movement, Leanne Wood, our first female leader. Leanne broke down barriers and took our message further than before. It was her leadership that carried the story born here in Pwllheli all the way to the very top of Townhill in Swansea. To my mum, and to me. And now, I’m proud to be standing on the shoulders of giants, of all of those who shaped our party over the last century, as a candidate for Plaid Cymru in next year’s Senedd elections.

And I do so with hope. Not just for next year’s election, but for the next generation. I’m currently expecting my first child. And I feel hopeful about raising her in a Wales that is fairer and more ambitious for the people who live here. A Wales that governs itself, with confidence.

This national milestone for Plaid Cymru is also a turning point for us in Cardiff.

Last year, I stood in Cardiff West in the General Election. With an amazing team of activists, we achieved the best result Plaid Cymru has ever had in a General election in Cardiff – and the second highest vote share increase towards Plaid Cymru nationally. Nearly 10,000 people in Cardiff West sent a clear message: Enough. Wales deserves better.

And this was in the very seat home to multiple Labour First Ministers. A party so out of touch, they couldn’t even find a candidate who lived in Wales, let alone Cardiff, to represent us. Labour has run Wales for over 25 years. And what do we have to show for it? Rising child poverty, Deepening inequality and a stagnating economy.

I think of communities like Ely, Riverside, and Butetown, in my constituency, on the doorstep of the Senedd, that have been left behind. Our politics can no longer fail those who need it most, it doesn’t have to be this way.

Next year, we have a real chance to elect a pro-Wales Government, led by Rhun. A government that will put the people before party.

A government that believes in our language, our communities, and our power to choose our own future.

As we have shown, time and time again over the past 100 years.

Plaid Cymru has always been the party of change.

As we enter our second century, we will do what our founders did 100 years ago, and be bold and deliver on a fairer, brighter future for Wales.

For the Wales, we all know is possible.

Diolch yn fawr.

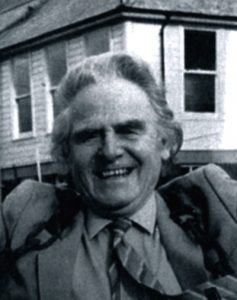

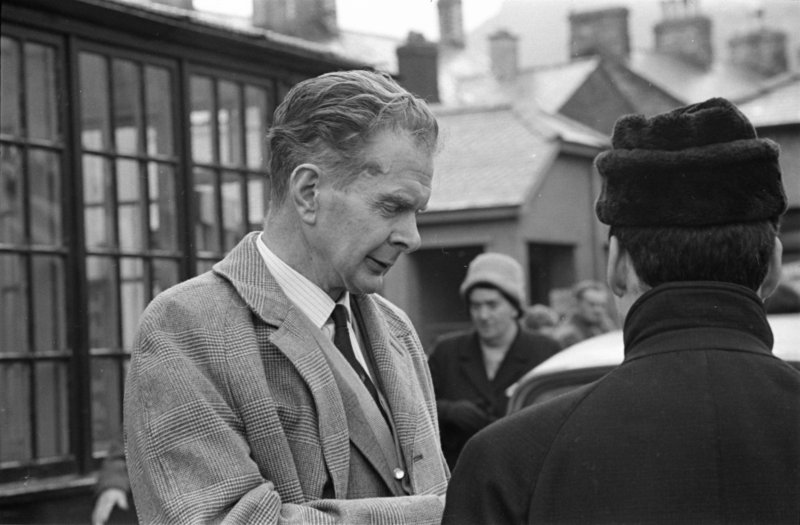

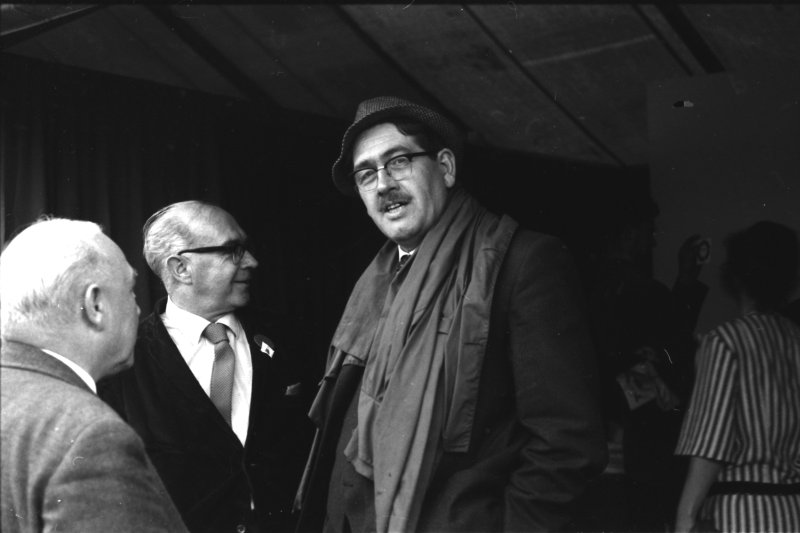

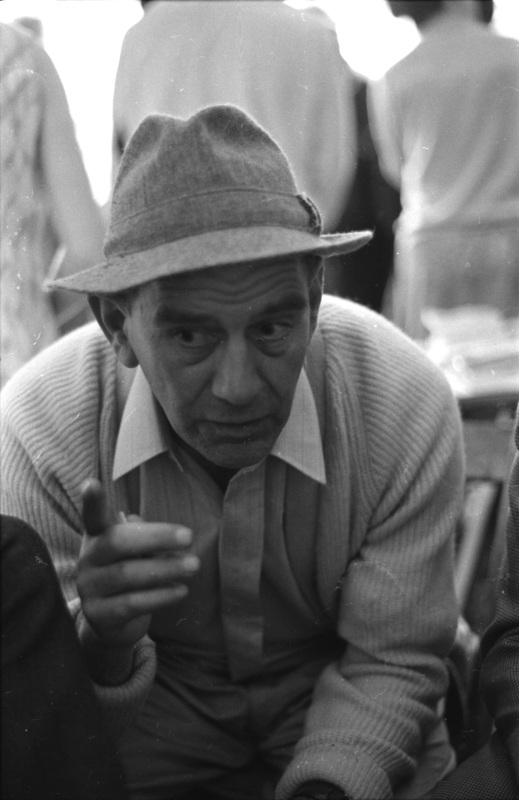

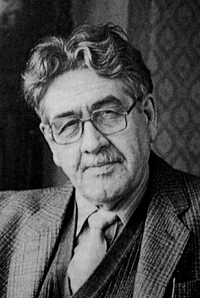

This year marks the centenary of the birth of one of Plaid Cymru’s most eminent Vie-Presidents, Dr Tudur Jones, who held the office from 1957 to 1964. As Vice-President, he provided Gwynfor with active support in public and invaluable advice in private. Living in Bangor, he was also in regular touch with General Secretary, Elwyn Roberts, who was based in the Bangor office. The three, Gwynfor, Tudur and Elwyn, were very much on the same wavelength, representing a nationalism that arose from a deep commitment to the Welsh language and that was firmly based on Christian values. As it happens, all three were Congregationalists. In the nineteen-sixties the Welsh Congregationalist Union resolved to support self-government for Wales, famously declaring that Wales’s problem was that it was too far from God and too near to England!

This year marks the centenary of the birth of one of Plaid Cymru’s most eminent Vie-Presidents, Dr Tudur Jones, who held the office from 1957 to 1964. As Vice-President, he provided Gwynfor with active support in public and invaluable advice in private. Living in Bangor, he was also in regular touch with General Secretary, Elwyn Roberts, who was based in the Bangor office. The three, Gwynfor, Tudur and Elwyn, were very much on the same wavelength, representing a nationalism that arose from a deep commitment to the Welsh language and that was firmly based on Christian values. As it happens, all three were Congregationalists. In the nineteen-sixties the Welsh Congregationalist Union resolved to support self-government for Wales, famously declaring that Wales’s problem was that it was too far from God and too near to England!