The Plaid Cymru History Society is keen to hear the voices of the women of Plaid Cymru. Do you have any stories, photos or archive you’d like to share with us? Get in touch! We’re now on Facebook under ‘Hanes Plaid Cymru History’ or you can email me direct on history@hanesplaidcymru.org

Author: admin

Berian Williams Film Eisteddfod 1959 – 1962

Cine Ffilm (no sound) Berian Williams

Eisteddfod Caernarfon 1959, Eisteddfod Caerdydd 1960, Eisteddfod Llanelli 1962

Plaid through the Ages

First Parliamentary Election Campaign in Flintshire 1959

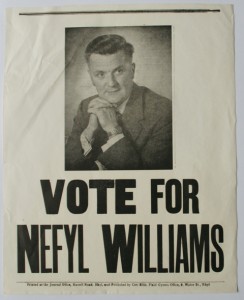

PLAID CYMRU’S FIRST PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION CAMPAIGN IN FLINTSHIRE Philip Lloyd Nefyl Williams was Plaid Cymru’s first Parliamentary candidate in Flintshire, when the county was  divided into two constituencies: East and West. He stood in 1959 in Flint West, which extended from inland St Asaph and coastal Rhyl and Colwyn Bay in the west to Holywell and Mold in the east and included numerous villages. Industrial Flint and Deeside and the detached rural area of Maelor beyond Wrexham (bordered mainly by Cheshire and Shropshire) were all in Flint East. I first met Nefyl in August 1958, when he chaired one of the discussion groups in the Summer School held in conjunction with the Party’s annual conference at Cyfarthfa Castle, Merthyr Tudful. Tall, silver-haired and soft-spoken, he made an immediate impression on me as he guided our deliberations with skill and patience. Little did I realize at the time that, within weeks, I would be part of Plaid’s organisation in his native north-east Wales. In the September I embarked on my teaching career in the county town of Mold and was soon invited to be a member of the Flint West Pwyllgor Rhanbarth (Constituency Committee). As I state above, Plaid Cymru first contested that constituency in 1959. It came as a surprise and a challenge to us, since we hadn’t thought of Rhyl, Mold etc as being promising politically. But Party President Gwynfor Evans thought otherwise. He came to a Pwyllgor Rhanbarth meeting and suggested in his gentlemanly but persuasive way that we contest the next election. I must confess that my immediate reaction was one of amused incredulity. But Gwynfor’s view prevailed. We have, by now, fought Flint West and its successor Delyn (minus St Asaph, Rhyl and Prestatyn but including Flint) ever since. Also Flint East from 1966 onwards (and the later Alyn and Deeside, minus Flint and Maelor), with Gwilym Hughes, my colleague at Ysgol Glan Clwyd, Rhyl (the country’s first Welsh-medium secondary school) as candidate on the first two occasions. Who was to be Plaid Cymru’s first candidate? Gwynfor proffered a name: Richard Hall Williams, lecturer at Connah’s Quay College of Further Education. He wasn’t a party member, but obviously highly regarded by Gwynfor (both hailed from Barry). Sadly, by now deceased, he was later responsible for agriculture at the Welsh Office, and his wife Nia became joint editor of the Welsh-language women’s periodical Hon with Marion Arthur Jones. The late Professor Stephen J. Williams famously and successfully defended its right to be so called when the publishers of She objected. ‘Hon’ did not mean ‘She’, he maintained, but ‘this feminine thing’. Who could argue with such a distinguished academic! To revert to Plaid Cymru and 1959. A three-man deputation was detailed to visit Richard Hall Williams at his home near the college. Led by Nefyl as Pwyllgor Rhanbarth chairman, it included Len Davies of Mold and myself. The clear understanding was that if our invitation were declined Nefyl would be candidate. Declined it was, amicably. So I hold the honour (?) of being among those few who first knew that Nefyl Williams was to be the party’s standard-bearer in that unpromising part of the country – all thanks to Gwynfor. Nefyl was a product of industrial Deeside and had been employed on strategic work at the John Summers steelworks in Shotton during World War II. He then qualified as a teacher and taught art at the Alun Grammar School, Mold. He and his wife Myfanwy learned Welsh as adults and ensured that their son Gwynfor received Welsh-medium education in a county which pioneered in the field, led by inspirational Director of Education Dr B. Haydn Williams. The Welsh spelling of his forename, clearly a modification of ‘Neville’, is an indication of his adherence to the national tongue. But, when Mold’s Ysgol Maes Garmon (secondary, Welsh-medium) was opened in 1961, he declined an invitation to apply for the post of Head of Art because, he said with typical and unnecessary modesty, his Welsh was not good enough. In the meeting held at Prestatyn to adopt Nefyl formally as candidate, he was introduced from the chair by the Reverend R.R. Jones as ‘Nefyl Williams B.A’, not in respect of his academic qualifications (he was not a graduate) but as a recognition of his personality: on this occasion ‘B.A.’ represented the words ‘bachgen annwyl’ [dear boy]. The results of the election were as follows:- Nigel Birch (Conservative) 20.446 (52.05%) Ronald Waterhouse (Labour) 12.925 (32.90%) L.E. Roberts (Liberal) 4,319 (10.99%) Nefyl Williams (Plaid Cymru) 1,594 (4.06%) Nefyl was named on the ballot paper as ‘E.N.C. Williams’. The ‘E’ stood for Ernest; the ‘C’ for Coppack, a common Deeside surname. Those days, public meetings were held at election times. D.J. Thomas, stalwart Plaid member and head-teacher of Ysgol Hiraddug (the primary school at the village of Diserth) played a major part in this aspect of our campaign together with agent Miss Ceri Ellis. Times were arranged for the major towns and itineraries drawn up combining several villages each evening. D.J. also insisted that we hold a post-election ‘celebration’ at the Urdd Hall in Diserth to congratulate Nefyl on his vote. While the votes were being counted at the Alun School, those cast for the Labour candidate were so numerous that some of the space for Nefyl’s ballot papers was re-allocated to that party. ‘He’s doing jolly well’, observed Nigel Birch generously to me, pointing to the apparently strong support for Plaid Cymru. It did not please me to correct the impression wrongly conveyed! Nefyl Williams stood for a second time in 1964. The results were:- Nigel Birch (Conservative) 18,515 (45.7%) William H. Edwards (Labour) 13,298 (32.8%) D. Martin Thomas (Liberal) 7,482 (18.5) Nefyl Williams (Plaid Cymru) 1,195 (3.0%) I was a newcomer to Flintshire when I started teaching there in September 1958; so I was not fully aware of the work done by Plaid members previously. It would therefore be invidious of me to mention any more names. In fact, I might never have been involved in the 1959 campaign at all. Nefyl, Ceri and I were all teachers employed by Flintshire County Council. So was Chris Rees, who, like me, was teaching at Ysgol Glan Clwyd at the time; he was released to be Plaid candidate in Swansea East (where he was to gain 10.5% of the votes). I had hoped to be agent to John Howell in the party’s first election campaign in Caerffili. But Flintshire’s Deputy Director of Education M.J. Jones (a long-standing Plaid member) thought it unwise for four teachers from the same party (two of them from the same high-profile Welsh-medium school) to be released. John’s agent in that election (with an 8.82% vote) was gas salesman Alf Williams, whom I refer to elsewhere in the Society’s website in connection with the illegal radio broadcasts of the 1960s.

divided into two constituencies: East and West. He stood in 1959 in Flint West, which extended from inland St Asaph and coastal Rhyl and Colwyn Bay in the west to Holywell and Mold in the east and included numerous villages. Industrial Flint and Deeside and the detached rural area of Maelor beyond Wrexham (bordered mainly by Cheshire and Shropshire) were all in Flint East. I first met Nefyl in August 1958, when he chaired one of the discussion groups in the Summer School held in conjunction with the Party’s annual conference at Cyfarthfa Castle, Merthyr Tudful. Tall, silver-haired and soft-spoken, he made an immediate impression on me as he guided our deliberations with skill and patience. Little did I realize at the time that, within weeks, I would be part of Plaid’s organisation in his native north-east Wales. In the September I embarked on my teaching career in the county town of Mold and was soon invited to be a member of the Flint West Pwyllgor Rhanbarth (Constituency Committee). As I state above, Plaid Cymru first contested that constituency in 1959. It came as a surprise and a challenge to us, since we hadn’t thought of Rhyl, Mold etc as being promising politically. But Party President Gwynfor Evans thought otherwise. He came to a Pwyllgor Rhanbarth meeting and suggested in his gentlemanly but persuasive way that we contest the next election. I must confess that my immediate reaction was one of amused incredulity. But Gwynfor’s view prevailed. We have, by now, fought Flint West and its successor Delyn (minus St Asaph, Rhyl and Prestatyn but including Flint) ever since. Also Flint East from 1966 onwards (and the later Alyn and Deeside, minus Flint and Maelor), with Gwilym Hughes, my colleague at Ysgol Glan Clwyd, Rhyl (the country’s first Welsh-medium secondary school) as candidate on the first two occasions. Who was to be Plaid Cymru’s first candidate? Gwynfor proffered a name: Richard Hall Williams, lecturer at Connah’s Quay College of Further Education. He wasn’t a party member, but obviously highly regarded by Gwynfor (both hailed from Barry). Sadly, by now deceased, he was later responsible for agriculture at the Welsh Office, and his wife Nia became joint editor of the Welsh-language women’s periodical Hon with Marion Arthur Jones. The late Professor Stephen J. Williams famously and successfully defended its right to be so called when the publishers of She objected. ‘Hon’ did not mean ‘She’, he maintained, but ‘this feminine thing’. Who could argue with such a distinguished academic! To revert to Plaid Cymru and 1959. A three-man deputation was detailed to visit Richard Hall Williams at his home near the college. Led by Nefyl as Pwyllgor Rhanbarth chairman, it included Len Davies of Mold and myself. The clear understanding was that if our invitation were declined Nefyl would be candidate. Declined it was, amicably. So I hold the honour (?) of being among those few who first knew that Nefyl Williams was to be the party’s standard-bearer in that unpromising part of the country – all thanks to Gwynfor. Nefyl was a product of industrial Deeside and had been employed on strategic work at the John Summers steelworks in Shotton during World War II. He then qualified as a teacher and taught art at the Alun Grammar School, Mold. He and his wife Myfanwy learned Welsh as adults and ensured that their son Gwynfor received Welsh-medium education in a county which pioneered in the field, led by inspirational Director of Education Dr B. Haydn Williams. The Welsh spelling of his forename, clearly a modification of ‘Neville’, is an indication of his adherence to the national tongue. But, when Mold’s Ysgol Maes Garmon (secondary, Welsh-medium) was opened in 1961, he declined an invitation to apply for the post of Head of Art because, he said with typical and unnecessary modesty, his Welsh was not good enough. In the meeting held at Prestatyn to adopt Nefyl formally as candidate, he was introduced from the chair by the Reverend R.R. Jones as ‘Nefyl Williams B.A’, not in respect of his academic qualifications (he was not a graduate) but as a recognition of his personality: on this occasion ‘B.A.’ represented the words ‘bachgen annwyl’ [dear boy]. The results of the election were as follows:- Nigel Birch (Conservative) 20.446 (52.05%) Ronald Waterhouse (Labour) 12.925 (32.90%) L.E. Roberts (Liberal) 4,319 (10.99%) Nefyl Williams (Plaid Cymru) 1,594 (4.06%) Nefyl was named on the ballot paper as ‘E.N.C. Williams’. The ‘E’ stood for Ernest; the ‘C’ for Coppack, a common Deeside surname. Those days, public meetings were held at election times. D.J. Thomas, stalwart Plaid member and head-teacher of Ysgol Hiraddug (the primary school at the village of Diserth) played a major part in this aspect of our campaign together with agent Miss Ceri Ellis. Times were arranged for the major towns and itineraries drawn up combining several villages each evening. D.J. also insisted that we hold a post-election ‘celebration’ at the Urdd Hall in Diserth to congratulate Nefyl on his vote. While the votes were being counted at the Alun School, those cast for the Labour candidate were so numerous that some of the space for Nefyl’s ballot papers was re-allocated to that party. ‘He’s doing jolly well’, observed Nigel Birch generously to me, pointing to the apparently strong support for Plaid Cymru. It did not please me to correct the impression wrongly conveyed! Nefyl Williams stood for a second time in 1964. The results were:- Nigel Birch (Conservative) 18,515 (45.7%) William H. Edwards (Labour) 13,298 (32.8%) D. Martin Thomas (Liberal) 7,482 (18.5) Nefyl Williams (Plaid Cymru) 1,195 (3.0%) I was a newcomer to Flintshire when I started teaching there in September 1958; so I was not fully aware of the work done by Plaid members previously. It would therefore be invidious of me to mention any more names. In fact, I might never have been involved in the 1959 campaign at all. Nefyl, Ceri and I were all teachers employed by Flintshire County Council. So was Chris Rees, who, like me, was teaching at Ysgol Glan Clwyd at the time; he was released to be Plaid candidate in Swansea East (where he was to gain 10.5% of the votes). I had hoped to be agent to John Howell in the party’s first election campaign in Caerffili. But Flintshire’s Deputy Director of Education M.J. Jones (a long-standing Plaid member) thought it unwise for four teachers from the same party (two of them from the same high-profile Welsh-medium school) to be released. John’s agent in that election (with an 8.82% vote) was gas salesman Alf Williams, whom I refer to elsewhere in the Society’s website in connection with the illegal radio broadcasts of the 1960s.

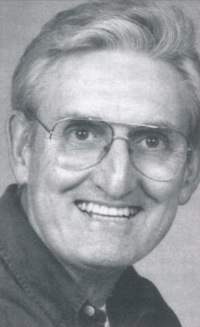

Rhobert ap Steffan 1947 – 2011

Rhobert ap Steffan In the early hours of Tuesday 11th of January 2012, Wales lost one of her most patriotic sons, Rhobert ap Steffan. Born in Hove, Sussex in 1948 of Welsh parents, the late Rev. Stanley & Mrs. Muriel Hinton, he was brought up and schooled in that proud South Wales valleys town, Treorci, a coalmining epicentre of our age-old struggle for cultural and political survival. He was a high spirited, warmhearted, likeable personality who thoroughly enjoyed socializing and a good old banter with his many friends and associates. It was through this very warm-heartedness that he gravitated, naturally, towards that early Plaid Cymru stalwart and character, Glyn James. Glyn became a life-long friend and welcomed him into the arms of the Plaid. He joined the party in the early 60’s and because of his rebel spirit and his (very) vocal advocacy of the inalienable rights of nations to self determination; he acquired the nickname of ‘Castro’ and was affectionately known as such throughout his life. The radical nature of his Welsh politics was triggered by two key events, the first being the 1965 enforced evacuation of the Welsh-speaking village of Capel Celyn in North Wales’ Tryweryn Valley, drowned to supply Liverpool industry with water. This took place despite there being viable alternatives, despite massive demonstrations and despite total Welsh parliamentary opposition. The other, seminal, event followed close on, in 1966, when an unsafe coal-tip slid into Aberfan’s Pantglas Junior School, near Merthyr Tudful, killing 116 children and 12 adults, as a result of what he considered criminal negligence by the National Coal Board. In 1966 he visited Dublin to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, following this up with active participation in the 1969 Anti-Investiture Campaign. seeing in all the fawning and show-biz pageantry a sycophantic celebration of his nation’s domination by another. A friend of Julian Cayo Evans and other leaders of the Free Wales Army, he was never openly implicated in its clandestine activities, preferring to put his skills to good use staging protests and rallies. Tired of all this, and of the pressure put upon him because of his radical views, he decided to get away from it all and fulfill an oft-expressed ambition. He followed in the wash of the Mimosa and sailed, in a cargo ship, to Patagonia, the Gwladfa of legend. After a year of many adventures among the welcoming locals (including being detained by police as a suspected communist guerilla whilst hitching through the land!), he returned to Wales with perfect Welsh flowing from his lips, despite having left his nation as a monoglot English speaker. His next step was to qualify as a teacher of art which he taught, through the medium of Welsh and with rewarded success, in West Wales as Head of the Art Department in Llanymddyfri Comprehensive School, It was after this, in the mid-seventies, that he met, on the Maes of the Cricieth Eisteddfod, his future wife, supporter and love of his life, Marilyn, with whom he had three children, Iestyn, Rhys and Sioned. Throughout his career and afterwards he worked tirelessly to support the Local Government and Parliamentary candidates of Plaid Cymru. He also stood as a council candidate himself, on a number of occasions. Other worthy organisations supported by Rhobert at various periods of his life included the Swansea based Young Nationalist Association, Y Gweriaethwyr, Cofiwn and Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg. Working with the community, Rhobert was the inspiration and driving force behind the project to commission Toby and Gideon Petersen to create the inspiring stainless steel memorial to Llywelyn ap Gruffydd Fychan, erected by the remains of Llanymddyfri castle. Llywelyn had led English forces a merry dance to allow Owain Glyndwr to escape the forces of England’s King Henry IV. As punishment for his actions, Llywelyn was condemned to be executed in the town square. (Llywelyn was hung, drawn, and then, before he was quite dead, his stomach was cut out and cooked in front of him. He was then quartered.) In the same vein, Rhobert was a member of the organising group of the Owain Lawgoch Society, whose wish was to build a permanent memorial to Owain, who was a grand nephew of Prince Llywelyn the Last and recognised by the King of France as Prince of Wales. (After a lifetime of fighting on the side of the French King, the Scot Jon Lamb, acting on the orders of the Regent of England assassinated him. Three times Owain’s sea-borne invasion of Wales was thwarted by storms. He was murdered whilst besieging the castle of Mortagne sur Gironde in 1378.) The statue campaign was successful and it was unveiled, near the church of Saint-Léger in Mortagne, by Rosemary Butler AM, Chair of the National Assembly’s Culture Committee, in 2003. As you have, no doubt, gathered by now, Rhobert’s contributions to the Welsh cause, be they based within or outside of Plaid Cymru, were multifarious; indeed, they prove almost impossible to list in full. He was an invaluable canvasser for Adam Price MP and Rhodri Glyn AM, and contributed immensely to the politics of the Llangadog ward, for which he was twice a candidate. Realising the value of publicity in the successful passing of a message to the public, he was one of the prime organisers of the campaign to encourage people to ignore the 2001 Census forms, since they contained no tick box acknowledging Welsh Nationality. Rhobert and a doughty band of patriots journeyed through villages and towns, the length and breadth of Wales, encouraging people to stuff their Census forms into a coffin, to be buried ‘somewhere’ after its last stop outside the National Assembly. Very many forms were stuffed into the coffin, but no prosecutions resulted and the 2011 census included the ‘Welsh’ tick box – a direct result, perhaps? After retiring early from teaching, he played an important part in the development of Cambria Magazine, to which he was appointed ‘Editor at Large’ and it was with the then editor and founder, Henry Jones Davies, that the idea of establishing an annual Saint David’s Day Parade through Cardiff was mooted, then swiftly realised. The Parade, ‘Y Gorymdaith Gwyl Dewi’ is now very large indeed, with representatives from the other Celtic nations taking part. In fact, it now rivals that taking place through Dublin on Saint Patrick’s Day. Throughout his political life, Rhobert maintained a huge interest in the affairs of the other Celtic nations, with many a visit and cultural link to Brittany, Ireland, Cornwall and the Gaelic- speaking islands of Scotland. He had always planned a return to Y Wladfa, and in 2008 he fulfilled his ambition. Mencap Cymru, the charity that makes a difference to the lives of adults and children with learning difficulties, had organised a sponsored walking trip through the Southern Andes to raise funds. All taking part had to raise at least £3,500, but Rhobert managed nearly £10,000. After the trek, he stayed on to make a very personal gift of gratitude to the people for teaching him Welsh by distributing copies of the, newly published, Encyclopaedia of Wales to libraries and schools. He was quoted in a local Carmarthen paper thus “I will be there as a kind of unofficial Welsh ambassador and will try to help strengthen the ties between Y Wladfa and the ‘Old Country’. I spent a year in Y Wladfa in order to learn Welsh. I worked in a big ‘Estancia’ (ranch) near Trefelin in front of the Andes in Cwm Hyfryd, I spoke Welsh within a few months – I had no choice as almost no one spoke English!” Prior to 2010, not once, in 40 years, did he miss the annual commemoration of the death of our last prince, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, at the hands of English forces on the 11th December 1282. This is held around a remembrance column in Cilmeri, close to where he was killed. It was obvious that something was seriously amiss when he did not turn up in 2010. It was he, after all, who had done so much to convene the rally over the years. What most present didn’t know was that he had just been diagnosed with a particularly virulent form of cancer and had but a month to live. Keep a place for us by the bar in Tir na Nòg, Castro…. You are sadly missed. John Page and Gareth ap Siôn

Rhobert ap Steffan In the early hours of Tuesday 11th of January 2012, Wales lost one of her most patriotic sons, Rhobert ap Steffan. Born in Hove, Sussex in 1948 of Welsh parents, the late Rev. Stanley & Mrs. Muriel Hinton, he was brought up and schooled in that proud South Wales valleys town, Treorci, a coalmining epicentre of our age-old struggle for cultural and political survival. He was a high spirited, warmhearted, likeable personality who thoroughly enjoyed socializing and a good old banter with his many friends and associates. It was through this very warm-heartedness that he gravitated, naturally, towards that early Plaid Cymru stalwart and character, Glyn James. Glyn became a life-long friend and welcomed him into the arms of the Plaid. He joined the party in the early 60’s and because of his rebel spirit and his (very) vocal advocacy of the inalienable rights of nations to self determination; he acquired the nickname of ‘Castro’ and was affectionately known as such throughout his life. The radical nature of his Welsh politics was triggered by two key events, the first being the 1965 enforced evacuation of the Welsh-speaking village of Capel Celyn in North Wales’ Tryweryn Valley, drowned to supply Liverpool industry with water. This took place despite there being viable alternatives, despite massive demonstrations and despite total Welsh parliamentary opposition. The other, seminal, event followed close on, in 1966, when an unsafe coal-tip slid into Aberfan’s Pantglas Junior School, near Merthyr Tudful, killing 116 children and 12 adults, as a result of what he considered criminal negligence by the National Coal Board. In 1966 he visited Dublin to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, following this up with active participation in the 1969 Anti-Investiture Campaign. seeing in all the fawning and show-biz pageantry a sycophantic celebration of his nation’s domination by another. A friend of Julian Cayo Evans and other leaders of the Free Wales Army, he was never openly implicated in its clandestine activities, preferring to put his skills to good use staging protests and rallies. Tired of all this, and of the pressure put upon him because of his radical views, he decided to get away from it all and fulfill an oft-expressed ambition. He followed in the wash of the Mimosa and sailed, in a cargo ship, to Patagonia, the Gwladfa of legend. After a year of many adventures among the welcoming locals (including being detained by police as a suspected communist guerilla whilst hitching through the land!), he returned to Wales with perfect Welsh flowing from his lips, despite having left his nation as a monoglot English speaker. His next step was to qualify as a teacher of art which he taught, through the medium of Welsh and with rewarded success, in West Wales as Head of the Art Department in Llanymddyfri Comprehensive School, It was after this, in the mid-seventies, that he met, on the Maes of the Cricieth Eisteddfod, his future wife, supporter and love of his life, Marilyn, with whom he had three children, Iestyn, Rhys and Sioned. Throughout his career and afterwards he worked tirelessly to support the Local Government and Parliamentary candidates of Plaid Cymru. He also stood as a council candidate himself, on a number of occasions. Other worthy organisations supported by Rhobert at various periods of his life included the Swansea based Young Nationalist Association, Y Gweriaethwyr, Cofiwn and Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg. Working with the community, Rhobert was the inspiration and driving force behind the project to commission Toby and Gideon Petersen to create the inspiring stainless steel memorial to Llywelyn ap Gruffydd Fychan, erected by the remains of Llanymddyfri castle. Llywelyn had led English forces a merry dance to allow Owain Glyndwr to escape the forces of England’s King Henry IV. As punishment for his actions, Llywelyn was condemned to be executed in the town square. (Llywelyn was hung, drawn, and then, before he was quite dead, his stomach was cut out and cooked in front of him. He was then quartered.) In the same vein, Rhobert was a member of the organising group of the Owain Lawgoch Society, whose wish was to build a permanent memorial to Owain, who was a grand nephew of Prince Llywelyn the Last and recognised by the King of France as Prince of Wales. (After a lifetime of fighting on the side of the French King, the Scot Jon Lamb, acting on the orders of the Regent of England assassinated him. Three times Owain’s sea-borne invasion of Wales was thwarted by storms. He was murdered whilst besieging the castle of Mortagne sur Gironde in 1378.) The statue campaign was successful and it was unveiled, near the church of Saint-Léger in Mortagne, by Rosemary Butler AM, Chair of the National Assembly’s Culture Committee, in 2003. As you have, no doubt, gathered by now, Rhobert’s contributions to the Welsh cause, be they based within or outside of Plaid Cymru, were multifarious; indeed, they prove almost impossible to list in full. He was an invaluable canvasser for Adam Price MP and Rhodri Glyn AM, and contributed immensely to the politics of the Llangadog ward, for which he was twice a candidate. Realising the value of publicity in the successful passing of a message to the public, he was one of the prime organisers of the campaign to encourage people to ignore the 2001 Census forms, since they contained no tick box acknowledging Welsh Nationality. Rhobert and a doughty band of patriots journeyed through villages and towns, the length and breadth of Wales, encouraging people to stuff their Census forms into a coffin, to be buried ‘somewhere’ after its last stop outside the National Assembly. Very many forms were stuffed into the coffin, but no prosecutions resulted and the 2011 census included the ‘Welsh’ tick box – a direct result, perhaps? After retiring early from teaching, he played an important part in the development of Cambria Magazine, to which he was appointed ‘Editor at Large’ and it was with the then editor and founder, Henry Jones Davies, that the idea of establishing an annual Saint David’s Day Parade through Cardiff was mooted, then swiftly realised. The Parade, ‘Y Gorymdaith Gwyl Dewi’ is now very large indeed, with representatives from the other Celtic nations taking part. In fact, it now rivals that taking place through Dublin on Saint Patrick’s Day. Throughout his political life, Rhobert maintained a huge interest in the affairs of the other Celtic nations, with many a visit and cultural link to Brittany, Ireland, Cornwall and the Gaelic- speaking islands of Scotland. He had always planned a return to Y Wladfa, and in 2008 he fulfilled his ambition. Mencap Cymru, the charity that makes a difference to the lives of adults and children with learning difficulties, had organised a sponsored walking trip through the Southern Andes to raise funds. All taking part had to raise at least £3,500, but Rhobert managed nearly £10,000. After the trek, he stayed on to make a very personal gift of gratitude to the people for teaching him Welsh by distributing copies of the, newly published, Encyclopaedia of Wales to libraries and schools. He was quoted in a local Carmarthen paper thus “I will be there as a kind of unofficial Welsh ambassador and will try to help strengthen the ties between Y Wladfa and the ‘Old Country’. I spent a year in Y Wladfa in order to learn Welsh. I worked in a big ‘Estancia’ (ranch) near Trefelin in front of the Andes in Cwm Hyfryd, I spoke Welsh within a few months – I had no choice as almost no one spoke English!” Prior to 2010, not once, in 40 years, did he miss the annual commemoration of the death of our last prince, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, at the hands of English forces on the 11th December 1282. This is held around a remembrance column in Cilmeri, close to where he was killed. It was obvious that something was seriously amiss when he did not turn up in 2010. It was he, after all, who had done so much to convene the rally over the years. What most present didn’t know was that he had just been diagnosed with a particularly virulent form of cancer and had but a month to live. Keep a place for us by the bar in Tir na Nòg, Castro…. You are sadly missed. John Page and Gareth ap Siôn  “Rhobert, with the support of the community, was the inspiration for the project to commission Toby and Gideon Petersen to create a memorial in steel to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd Fychan which can now be seen by the ruins of Llandovery Castle. “

“Rhobert, with the support of the community, was the inspiration for the project to commission Toby and Gideon Petersen to create a memorial in steel to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd Fychan which can now be seen by the ruins of Llandovery Castle. “

Winning Carmarthen

Publishing Leaflets and Booklets

Plaid Cymru History Society is collecting old Plaid publications. During and after J.E.Jones’ period as Secretary the leaders of Plaid Cymru were very active setting out their position and vision for the furture of Wales.

The publications that have recently been put on the Society’s website include ‘Wales as an Economic Entity’ and ‘TV in Wales’ by Gwynfor Evans and ‘Self-Government’ by Phil Williams.

Also on the website there are a number of leaflets from the 1960s including the 1966 By-election and Vic Davies’ By-election in the Rhondda.

Dafydd Huws 1936 – 2011

Dafydd Huws 1936 – 2011

Tribute by Dafydd Williams

Dafydd Huws, who died aged 75 during 2011, was a leading member of Plaid Cymru who helped hold the party together at a crucial phase in its history.

Dafydd Huws, who died aged 75 during 2011, was a leading member of Plaid Cymru who helped hold the party together at a crucial phase in its history.

He combined three careers – as a psychiatrist, farmer and politician – bringing to each of them a capacity for innovation and for speaking his mind. Later in life he turned to the promotion of renewable energy as a way of bring new life to rural communities in West Wales.

I first met him in 1964, as a new member of Côr Aelwyd Caerdydd, the Urdd youth choir led by Alun Guy. Dafydd was a star member of the tenor section, whose musical ability made him exempt from regular choir practice. You couldn’t miss his mischievous sense of humour and his store of jokes. Dafydd was the first I heard to perform “I’m Kerdiff born and Kerdiff bred” – although he was actually born in Kenya.

He worked as a leading psychiatrist, who became Clinical Director of South Glamorgan psychiatry service. This was a truly high pressure job, with responsibilities ranging from the treatment of the severely disturbed to preparation of evidence for court cases. Later on, I would see him in his work environment at Tegfan in Cardiff’s Whitchurch Hospital, when I called during his lunchtime break to prepare for Plaid Cymru executive meetings. There I saw for myself the way he engaged with professionals and patients alike with never failing ease and humour.

Dafydd’s natural gift for communication meant he was soon in demand by the media, making frequent appearances on radio and television on medical issues and current affairs in both Welsh and English. His love of Wales, its landscape, language and culture was boundless, and later in life he mastered the intricacies of Welsh metrical poetry, becoming an accomplished practitioner in the art of cynghanedd.

His second career, in agriculture, provided a welcome relief from the strains of medical life. Soon after I got to know him, he took the major gamble of acquiring part ownership of Mynydd Gorddu, an upland farm in the Pontgoch area near Aberystwyth, close to his childhood home. Dafydd’s commitment reflected his deep attachment to the life of rural Wales rather than a commercial investment, although he proved adept at running a business as well as being a caring employer.

But most people will remember him for his involvement with politics as a lifelong member of Plaid Cymru. In the heady days that followed the 1966 Carmarthen byelection, Dafydd took on the task of contesting the Plasmawr ward, an area that included Fairwater and part of Ely in Cardiff West. And in 1969 his charisma and enthusiasm carried the day, winning Plaid Cymru’s first ever seat on Cardiff City Council with a razzmatazz campaign that included motorcades and yellow dayglo posters galore.

He was to contest Cardiff West against George Thomas, later Viscount Tonypandy, fighting the 1970 and the two 1974 general elections. By the late 1970s, his services as an inspirational candidate were required in the more winnable seat of Ceredigion, his home county. Dafydd was far from keen. Apart from the heavy demands of being a frontline candidate, there was always the dread possibility of winning! Life as an MP in Westminster held no appeal for him, and he frequently told me how he admired the ‘two Dafydds’ (Wigley and Elis Thomas) who showed every sign of relishing their job in the House of Commons. What swung the balance was a letter from Gwynfor Evans, concluding with the words, ‘Dafydd, derbyniwch hyn fel eich tynged’ – accept this as your destiny, or fate!.

In the same way, he accepted the role of Chairman of Plaid Cymru in the wake of the failed 1979 referendum and the loss of Gwynfor Evans’ seat at Carmarthen. This is never an easy job (and it was and is of course unpaid). In the circumstances of the 1980s, at a time of considerable infighting over the direction of the party, it was a veritable bed of nails. Dafydd saw it as his role to steady the ship; accepting that the frequent attacks he had to endure went with the territory. Plaid Cymru owes him a huge debt of gratitude for holding the party together and preparing for successful 1997 referendum and later Assembly election advance.

Perhaps that experience was good training for the new role of pioneering renewable energy. Dafydd was an innovator by instinct: and he saw that the imperative of developing wind energy could help provide rural communities with a much needed economic input – providing that control was in the hands of local people. He succeeded in developing a wind farm at Mynydd Gorddu in the face of opposition, mainly from incomers to the area. That involved a running battle over the red tape surrounding supply of power through the National Grid, which made local control well nigh impossible.

A more ambitious project near Tregaron, Camddwr, was held up by similar bureaucratic issues – this time the interpretation of how Ministry of Defence low flying restrictions impacted on wind farm development. Dafydd was not prepared to accept the civil service view; so he travelled all the way to Aberdeen to attend an energy policy convention to lobby a senior MoD official who just happened to be a former student at Aberystwyth. As suspected, the strict interpretation turned out to be misplaced; and the project may well proceed, although too late for Dafydd to witness its fruition. And it was during this mission to Aberdeen that he noticed the first signs of the cancer that he fought so bravely for the next seven years.

Whatever the challenges that confronted him in his professional and political life, there is no doubting the enormous happiness he found in his family. Meeting Rhian brought to an end his career as one of Wales’ most eligible bachelors but it opened up his life as a husband and father of three daughters and two sons, who were a source of great happiness and fulfilment.

To his family and friends, Dafydd will remain the source of many fond memories: to all of us, his life is an inspiration to make Wales the free, self-respecting nation that he sought for future generations.

JE – Architect of Plaid Cymru Address by Dafydd Williams

During the annual conference in Llandudno in September 2011, the Plaid Cymru History Society organised a meeting to commemorate the life of JE Jones, who served as party General Secretary between 1930 and 1962. This is the address by the Chair of the society and one of his successors in the post, Dafydd Williams.

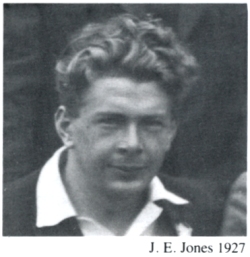

One of the earliest photographs from Plaid Cymru’s archives shows a group of people gathered at the 1927 Summer School at Llangollen. At the end of the front row is a young man with curly hair, his face full of energy and enthusiasm. Naturally I never knew the strong, young JE Jones who delighted in day-long expeditions across the mountains of Wales. By the time I met him in the mid 1960s, his robust good health had left him – a consequence, some said, of his incessant overwork for the cause of Wales. But his spirit and dedication to his country were as strong as ever.

John Edward Jones was born in December 1905. That meant he was ten years or so younger than Saunders Lewis and Lewis Valentine, and unlike them part of the generation that escaped the horrors of the First World War. His childhood home lay near the village of Melin-y-Wig, a hilly district about seven miles from Corwen and ten from Ruthin, the stamping ground of Owain Glyndŵr.

From the high ground behind the family farm, Hafoty Fawr, a clear day would give you a 360-degree view of the mountainous heartland of Gwynedd, Clwyd and Powys, which he describes in a lyrical passage in his important book Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid – half autobiography, half history of Plaid’s first forty years. It would be fair to describe JE as a patriot from his earliest days, drawing inspiration from the mountains of his birthplace: in fact he describes himself as ‘Mab y Mynydd’, the son of the mountain.

Before he had reached his first birthday, JE’s father died; but somehow his mother kept the family farm going with the help of her family, JE’s two brothers in particular, both of whom left school at 14 years of age. JE himself was to tread a very different path, despite his deep attachment the rhythm of agricultural life and the rural culture of Melin-y-Wig, with all its concerts and eisteddfodau. He won his way to Bala Boys Grammar School, Ysgol Tŷ Tomen, staying in Bala during the week. For all that Bala was a solidly Welsh-speaking area, everything in the school was in English. Was it this that fired up his lifelong support for Wales and the Welsh language? He tells the story of how he and a friend intervened to prevent a teacher picking on one of their fellow pupils who spoke little English – and succeeded in putting a stop to it. Then during the summer holidays in August 1923, after delivering eggs and butter to the village shop, he read a newspaper account of the meeting in Mold of a new movement with the odd title of ‘The Three Gs’, an acronym for y Gymdeithas Genedlaethol Gymreig, the Welsh National Society. This was one of the three groups that later came together to form Plaid Cymru; and a year or so later JE was to join it, as a first year university student at Bangor, where he studied Welsh, English and Mathematics, which he described as a “somewhat unusual combination”.[1]

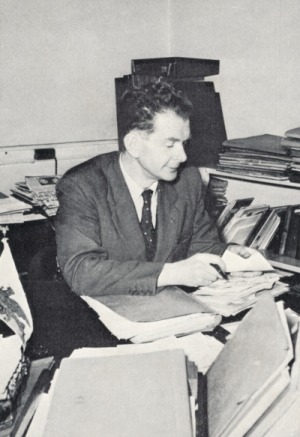

JE Jones – Architect of Plaid Cymru in his office in Caernarfon

Soon after, he heard reports of the launch of Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru in Pwllheli, and in October 1926 he attended a Plaid meeting in Caernarfon, filling in a membership form there and then. The forms were collected by HR Jones, a thin young man with a pale complexion: little did JE know that in a few years’ time he would be taking his place as Plaid Cymru’s general secretary. Within a month, a Plaid branch had been set up in the college in Bangor, with JE as secretary; by the summer it had nearly 80 members. JE stood as the party’s candidate in a mock election in November 1927 – and after a barnstorming campaign, he won! Could this have been Plaid’s first ever election victory? “I learnt then,” he was to say, “that it was easier to win over intelligent English people than a number of servile Welsh individuals.”[ii]

Once his University days were over, it was time to look for work. With a depression already looming, he applied for a teaching post in east London – and got it, one of four appointments out of 60 candidates. It seems most of the interview was spent discussing self-government for Wales! In no time at all, he had become secretary of Plaid Cymru’s London branch, although he also found time to play football for London Welsh Second XI and tennis during the summer.

Then came a decisive turning point in the young teacher’s life. After a long illness, HR Jones, the main driving force behind the foundation of Plaid Cymru, died. Despite fears about being able to afford it, the party leaders decided that a full-time successor had to be appointed. JE, together with a friend, the Guardian journalist

Gwilym Williams, decided they would both apply – using exactly the same wording, and giving each other’s name as a reference! JE was appointed – to a post he loved: “I was Secretary and Organiser of the movement for Welsh freedom from December 1930 until May 1962, when the old heart said it could take no more.”[iii]

It is interesting to compare the two Jones, HR a JE. One footnote, perhaps trivial but worth noting, is this: both of them succeeded in restoring the traditional names of their home communities; from Nasareth to Deiniolen in the case of HR, Cynfal to Melin-y-Wig in the case of JE. There was certainly a strong similarity in one aspect of their characters – an unswerving devotion to the cause of Wales and the Welsh language, and a vision of their country as taking its place among the world’s fully fledged nations. To which we can add the readiness to work without stop. I am grateful to Dewi Rhys, JE’s son, for these recollections of his father (my translation): “He was never idle. He would be on his feet about 5 every morning – either on the little typewriter, or in the greenhouse where he would ‘relax’ by transplanting hundreds of small plants, with the garden a sea of colour every summer. He was delighted to hear people making complimentary comments about the garden as they passed by. Even on holiday, he wasn’t idle. He would write diaries and bind them together as book after we came home.”[iv] Such commentaries were to form the basis for Tro i’r Swistir, the book he later wrote about their visits to Switzerland.

But the differences between the two are also revealing. As ever, JE is full of praise for his predecessor but he could not but observe the fact that party branches and rhanbarth organisations had languished and ceased to exist during HR’s illness: “To all intents, I was obliged to rebuild Plaid Cymru all over again.”[v] Plaid’s principal historian, D Hywel Davies, goes further, describing HR in these terms: “a restless visionary, longing for vigorous action on behalf of Wales rather than a desk role”. By contrast, JE “though prepared for radical action, was blessed with a painstaking nature more fitted to the task of careful organisational planning”.[vi] Hywel Davies also points to JE’s background as a University graduate and qualified teacher, concluding that this made him more comfortable among the membership Plaid was attracting.

JE took up his post on 1 December 1930, working from a small office in Caernarfon adjacent to the Pendref hotel where he took lodgings. What followed was a 32-year ‘stretch’ in which he became the lynch pin of party activity. JE soon established himself as the centre of communication and information for the party; and Plaid Cymru became noted for the quality and quantity of its publications. In the first four years of existence, it had published just one substantial pamphlet, Saunders Lewis’ Principles of Nationalism. Once JE took up the reins of office, Plaid began producing a steady stream of literature. It is worth noting that this output included several solid works on economic policy – including The Economics of Welsh Self-Government by Dr DJ Davies (July 1931) and two by Saunders Lewis – The Case for a Welsh National Development Council (1933) and Local Authorities and Welsh Industry (1934). These publications, supplemented Y Ddraig Goch, which slightly preceded the foundation of Plaid Cymru, and its English-language counterpart, Welsh Nationalist, set up in 1932.

The emphasis was very much on selling and sales campaigns rather than giving away; although JE developed the habit of what he called ‘meithrin tawel’ (quiet cultivation), sending the latest publication with a friendly covering letter to a selected range of prominent people – the artist Augustus John was one he said joined the party as a result.[vii] I recall (to my shame) Gwynfor Evans pointing frequently to the relative dearth of Plaid publications during the 1970s and 1980s by comparison with JE’s term of office.

Then there is PR. While persuading others to produce detailed publications, JE himself was master of collecting the telling quote and the killer fact, which he described as ‘bwledi’ – bullets. This led on naturally to press communications, in which he proved expert – both in crafting press statements and cultivating journalists. I like his restrained critique of some of his fellow Nationalists in this area: “I found one of the most difficult things, in the early years, was to educate our local officials – secretaries or correspondents – to write ‘effective pieces’ for the Press and to develop friendly relations with journalists. But that came, over time.”[viii] JE could have taught 21st century spin doctors a trick or two: his advice on using the Press remains as true today as ever, for all the changes brought by the age of the internet, Facebook and Twitter.

One early priority was building the party, from the tiny handful he inherited in 1930. This proved painfully slow, although JE set about the task in his typically systematic way, moving from county to county, badgering members to establish county committees and in due course branches. Saunders Lewis was characteristically acerbic about the rate of progress: at the end of 1935, after praising JE’s work, he asked: “But where are his disciples? An organiser of the same calibre in every Rhanbarth Committee would transform the course of Plaid Cymru.”[ix]

Here it’s worth recalling some home truths. Plaid Cymru was still small. It was also (in terms of the age of its members) overwhelmingly young. Because it was small and young it was also poor, very poor. This partly explains how few elections it fought – one Parliamentary seat in 1929, two in 1931 (Caernarfon county and the University of Wales), back down to one in 1935. By the way, 1935 was the first election for Plaid to use canvassing – a technique JE adapted from his contacts with parties in Denmark, Ireland and England. Local elections contested were also few and far between. Perhaps poverty isn’t the whole truth – the indefatigable DJ Williams complained bitterly at the lack of fighting spirit, describing Carmarthenshire county committee as “a dead body”.[x] This was 1935!

One technique JE pioneered to tackle Plaid’s financial problems was the St David’s Day Fund, based on the experiences of Fianna Fáil. The first appeal, in 1934, raised the princely sum of £250! Building party membership and funding went hand in hand with fighting campaigns – on a whole range of topics. Just one example – shortly after taking up his post JE launched a campaign to popularise use of the Welsh flag in place of the ubiquitous Union Jack. The first target was Caernarfon castle, whose Constable was none other than David Lloyd George. His opening gambit was typically modest, scarcely capable of rejection – simply equal status for the two flags on St David’s Day. A letter forwarded by Lloyd George to the Minister in London elicited a contemptuously negative response – just what JE was after of course. He promptly published it!

On St David’s Day 1932, clad top to toe in motor cycle gear, JE paid his sixpence and made his way to the top of the Eagle Tower, joined by three other conspirators, including Lloyd George’s nephew, WRP George. There they lowered the Union Jack, raised the Ddraig Goch and then stapled the ropes to the flagpole – JE’s planning of course included a hammer and staples in his rucksack. The spectacle of a large red dragon flag on the tower prompted cheers and a quick rendition of Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau from a crowd below; although the local constabulary soon appeared, and before long the Union Jack was back in its place. Later in the day, however, and quite independently, a group of Plaid students from Bangor showed up on the back of a lorry. They too got up to the Eagle Tower and succeeded in smuggling out the offending Union Jack, which met an unfortunate fate on the Maes.

The following St David’s Day saw a government U-turn. A large Draig Goch was raised as high as the Union Jack, and the ceremony was performed by none other than David Lloyd-George. Soon afterwards, the Welsh flag would fly from all government buildings on 1 March; and JE saw to it that party branches pressed the local authorities to follow suit. He then arranged production of more flags, selling them at a tidy profit.

Other campaigns involved moves to raise the status of the Welsh language – for example, shaming the Post Office into accepting prepaid envelopes with Welsh place names – building up to the successful drive to ensure Welsh language programmes on the BBC. A common theme in all these endeavours – and many more – was careful planning and a holistic approach – never missing out on an opportunity for good PR. This care was evident than during the burning of the Penyberth bombing school in September 1936, an operation remarkable for its secrecy and meticulous attention to detail. This included a spy – the young Alaw Non Rees, who from her upstairs window in Llanbedrog kept tabs on how much timber had arrived on site.

JE was one of seven people who played a direct role in the operation – he walked part of the way back to Caernarfon along the railway to avoid detection. The following morning in his lodgings he received a letter from Saunders Lewis – apologising for not informing him about the burning! It was of course an alibi – the Plaid leaders could not afford to have their office closed down and their organiser behind bars at such a crucial moment. JE remained free to organise nationwide protests. Dewi Rhys recalls seeing the bundles of telegrams of support sent to the Penyberth Three – Saunders Lewis, Lewis Valentine and DJ Williams – telegrams that JE had organised: by law they had to be delivered, even during a High Court trail, helping to maximise the impression of public support.[xi] He also arranged what I believe must still rank as the biggest ever party rally – a crowd of 12,000 welcomed the Penyberth Three back to Caernarfon from Wormwood Scrubs.

Penyberth and the two High Court trials that followed proved a pre-War high water mark for Plaid Cymru. JE argues that much of the new support the party won was dissipated by opposition to the coronation of George VI, a decision taken during Saunders Lewis’ prison sentence and a rare spell of sick leave for himself. Opponents also saw Lewis’ conversion to Catholicism as a chance to smear Plaid with the taint of fascism. The outbreak of War posed a huge challenge – even a mortal threat to the party’s existence, as Saunders Lewis openly admitted at the time. Yet somehow Plaid Cymru carried on, and even grew in influence as the war went on. The party hit back at its detractors with vigour and confidence. It resisted conscription, JE facing six separate courts and tribunals over three years, and doing so with some style. And it fought tooth and nail to save 40,000 acres of land in the Epynt range from seizure as a Ministry of War firing range. So in April 1940, JE found himself walking the mountains again, visiting every farm endangered; but London had its way.

Planning post-War election strategy – the SNP’s first MP Dr Robert McIntyre joins Plaid leaders in 1945

From 1942 the tide was clearly turning in the party’s favour. A by-election for the University of Wales seat saw Saunders Lewis take 23 per cent of the vote: JE notes (with satisfaction) that he was described as ‘cunning’ for his role as the “assiduous, astute and untiring agent”.[xii] And he had another reason to be happy. In 1940 he had married Olwen Roberts, secretary of the Caernarfon rhanbarth, the ceremony performed by Lewis Valentine. Two children, Angharad and Dewi Rhys, were to follow.

By 1945, Plaid Cymru emerged stronger than ever. For the first time it could lay some claim to be an all-Wales party, fighting seven seats in the general election. In the summer it chose a new leader, the 33-year-old Gwynfor Evans, and he and JE were to form a cohesive team for the next decade and a half. In fact, says Hywel Davies, it is from 1945 rather than 1925 than Plaid can be regarded as a political party, albeit still a party in embryo.[xiii]

Once again it fought a Ministry of War land grab, this time in Trawsfynydd, Meirionnydd and this time successfully. Again JE provided organisational flair: the police and army were outwitted by a diversionary group while the main protest used back lanes to stage a two-day blockade. By 1950 Plaid Cymru was fully engaged in the Parliament for Wales campaign and JE organised a series of rallies which would be held annually for a quarter of a century. The 1953 rally was one of the biggest seen in Cardiff. Unusually he took the chair – but his real input was planning and implementation. The build-up included a relay of torch bearers running from the Owain Glyndŵr Parliament House in Machynlleth to Sophia Gardens: JE ensured the speeches and messages went on long enough for the ensuing procession to be seen by crowds leaving Cardiff Arms Park.[xiv] He was also involved in the defence of the Tryweryn valley although by now he had more assistance.

JE chairs the 1953 Parliament for Wales rally in Sophia Gardens, Cardiff

Of course JE Jones was not without his critics. Some felt that someone of his background could not relate to the industrial, non-Welsh-speaking communities of south-east and north-east Wales. I think his track record shows otherwise. Tros Gymru is full of references to the need to appeal to those who do not speak Welsh. JE supported the move of the party’s office from Caernarfon to Cardiff in 1946 – in fact he personally located premises in 8 Queen Street. Dewi Rhys recalls that the official opening took place on 1 March, the day of his birth, with his father trying to be in two places at the same time – as usual![xv] His work enabled Plaid Cymru to spread its wings in the south after the war. For his part JE always showed a great reluctance to criticise fellow Nationalists. Here is one rare example: after praising the leadership of Saunders Lewis, he allowed himself this one comment: “But he did develop a tendency towards a mistaken prejudice sometimes against certain types of people; for example, he could suggest, about someone quite as courageous as himself, that pacifism was cowardice.”[xvi] The ‘someone’, of course, has to be Gwynfor Evans.

Others felt he was too close to the party elite; especially at times of strain within the ranks, as for example during the Tryweryn campaign. By 1950, the now ex-president Saunders Lewis was privately critical of what he called JE’s ‘parchusrwydd’, respectability, which he contrasted unfavourably with the militant tactics of the Welsh Republicans.[xvii] But JE was by his nature a loyalist, committed to supporting Plaid Cymru and its chosen leadership through thick and thin, whatever that might demand. He had proved himself more than ready for radical action: his willingness during the war years to oppose conscription as a nationalist and face prison demonstrates that. The ‘respectability’ of which Saunders Lewis complained was that of Plaid Cymru rather than JE: it reflected the determination of Gwynfor Evans to put post-War Plaid on course to be a truly all-Wales party rather than a nationalist pressure group.

Looking back, what is striking is JE’s willingness and ability to continue at his post, for all the problems and pressure Plaid Cymru faced. Could the party have held together during the 1930s, the 40s and the 50s without JE at the helm? Perhaps, but I find it hard to imagine how. His tombstone in Melin-y-Wig bears the dedication ‘JE Jones, Pensaer Plaid Cymru’ – a fitting tribute to the architect of Wales’ national movement.

JE Jones (1905-1970) is buried in the cemetery opposite the chapel in Melin-y-Wig, Denbighshire. A plaque on the wall of the former village school he attended also commemorates his life.

[1] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid. (Gwasg John Penry, Abertawe, 1970), p.37.

[ii] Ibid, p.40

[iii] Ibid, p70

[iv] Ebost i’r awdur gan Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, Mis Medi 2011.

[v] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.97.

[vi] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party 1925-1945: A Call to Nationhood (University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1983), p.187.

[vii] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.88.

[viii] Ibid, p.95.

[ix] Ibid, p.113.

[x] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party, p.204.

[xi] Email to the author by Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, September 2011.

[xii] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.276.

[xiii] D Hywel Davies, The Welsh Nationalist Party, p.268.

[xiv] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid. p 307.

[xv]Email to the author by Dr Dewi Rhys, Tudweiliog, September 2011.

[xvi] JE Jones, Tros Gymru: JE a’r Blaid, p.155.

[xvii] Emyr Hywel (Editor), Annwyl D.J. Llythyrau D.J., Saunders, a Kate. (Y Lolfa, Talybont, Ceredigion, 2007), p.182.